The following passage is excerpted from the author’s introduction to his new translation of a book written in 1525 by Antonio Vignali (1500-1559), a young Italian nobleman from Siena, entitled La cazzaria, or The Book of the Prick (Routledge, 2003). La cazarria was by far the bawdiest of many 16th-century Italian treatises on sex, in this case a dialogue between Arsiccio (Vignali himself) and his sexually naïve friend Sodo. Moulton notes early on that the book is openly homoerotic and that “It is clear that Arsiccio … very much prefers to have sex with men and is willing to openly assert and defend his preferences.”

AS WELL AS being a political allegory and an erotic myth, La cazzaria is also an apologia for sodomy. In this, Vignali’s dialogue represents a vernacular continuation of the humanist Latin tradition of learned—and often homoerotic—bawdy.

When Vignali wrote La cazzaria, Italy had long been notorious throughout western Europe as a hotbed of sodomy. The term “sodomy” was by no means a precise one in the period; it was used to refer to a wide variety of transgressive and nonprocreative sexual activities. In general, though, it referred to sexual activity between men, especially anal sex. So strong was the popular association of Italy with sodomy that in early modern Germany, the word for “sodomite” was Florenzer. There is as yet no detailed study of male homoeroticism in 16th-century Siena, but Michael Rocke’s Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence makes it clear that sex between men was an integral part of urban life in Tuscany. While homoerotic relations were by no means simply tolerated and the penalties for those convicted of sodomy could be very harsh indeed, sexual activity between males seems to have been common at all social levels.

In Lives of the Artists, Vasari records a story that may provide some insight into Sienese homoeroticism in the early 16th century. In 1515 a horse owned by the Sienese painter Giovanbatista Bazzi won the Palio, the town’s horse race. After the race it was the custom to shout the victor’s name in the streets of the city. On this occasion, instead of yelling “Bazzi!” the assembled crowds shouted “Sodoma! Sodoma!”—the nickname Bazzi had acquired through his open sexual interest in boys. The shouting of this provocative name brought the more conservative elements of the city into the streets in protest, and a riot ensued.

This story suggests the ambivalent place of homoeroticism in Renaissance Italian culture.

As the treatment of sodomites in Canto 15 of Dante’s Inferno makes clear, in late medieval theology sodomy was seen primarily as a sin of violence against God. By seeking sexual satisfaction with other men, a sodomite was going against God’s first commandment to be fruitful and multiply. Because sodomites make their naturally fertile bodies infertile, Dante places them next to the usurers, who by lending money at interest make infertile metal breed. There are few activities more dissimilar to the modern mind than buggery and banking, but for Dante and other medieval theologians, the two sins were related in their perversion of God’s gift of fertility.

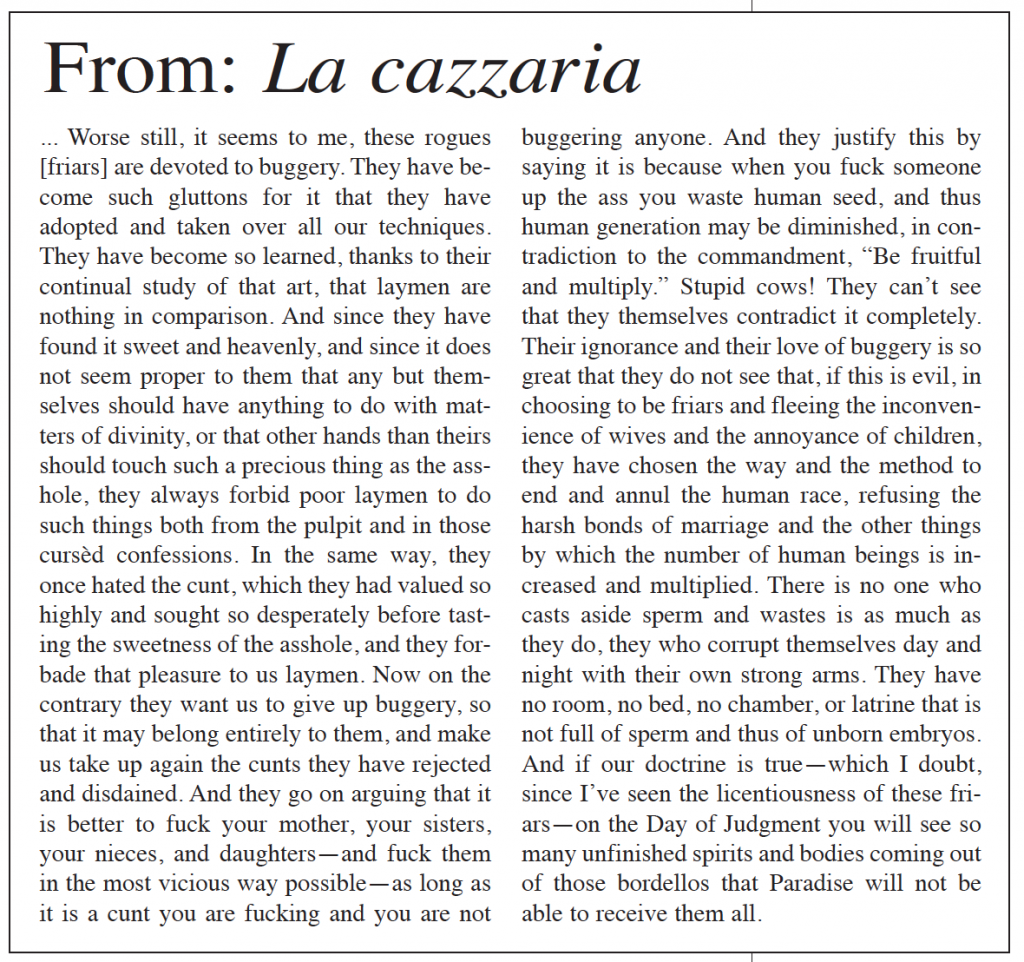

Arsiccio will have none of this; he sees such clerical denunciations of sodomy as obvious hypocrisy and argues that monks call buggery a sin so that no one but they will have the pleasure. Here as elsewhere his logic is resolutely secular and materialist. He goes on to attack the logic behind the Church’s condemnation of sodomy, arguing that by rejecting marriage for the “celibate” world of the religious orders, monks, priests, and friars themselves are guilty of the same “unnatural” denial of human fertility that in their view makes sodomy sinful:

They want us to give up buggery, so that it may belong entirely to them, and make us take up again the cunts they have rejected and disdained. And they go on arguing that it is better to fuck your mother, your sisters, your nieces, and daughters—and fuck them in the most vicious way possible—as long as it is a cunt you are fucking and you are not buggering anyone. And they justify this by saying it is because when you fuck someone up the ass you waste human seed, and thus human generation may be diminished, in contradiction of the commandment, “Be fruitful and multiply.” Stupid cows! They can’t see that they themselves contradict it completely. Their ignorance and their love of buggery is so great that they do not see that, if this is evil, in choosing to be friars and fleeing the inconvenience of wives and the annoyance of children, they have chosen the way and the method to end and annul the human race, refusing the harsh bonds of marriage and the other things by which the number of human beings is increased and multiplied.

In his insistence on seeing clerical traditions from a purely secular standpoint, Arsiccio anticipates much subsequent criticism of clerical celibacy.

Some scholars have related the high incidence of male homosexuality in the Renaissance to the fact that young men often delayed marriage until they were financially secure. In Italian cities, it was not uncommon for men to remain unmarried into their early thirties. In a society where the only fully acceptable sexual relationship was heterosexual marriage, this meant that many men would have between ten and fifteen years of sexual maturity in which licit activity was not an option. Given the tight social controls on respectable women, this meant most men sought sexual relations either with prostitutes or with other men.

Homosexual relations between men in Renaissance Italy were almost always between adult men and adolescent boys. The adult partner traditionally took the dominant role in the relationship, both socially and physically. As evidence from legal records demonstrates, often the younger men were penetrated anally by the older men, and not vice versa. Generally speaking, the passive position was seen as more shameful—males who allowed themselves to be sexually penetrated were perceived to be acting as women and therefore debasing themselves. Such a passive role was especially shameful in the case of an adult man. Boys, not fully mature, might be allowed to act in feminine ways—after all, their hairless bodies were frequently praised for being smooth and soft, like women’s. But an adult man had no excuse: taking the “female” role in intercourse was a betrayal of his masculine identity and the social authority that went with it.

This principle is demonstrated in La cazzaria’s portrayal of the weak monti [political factions]as Cunts and Assholes, which, in the dialogue’s vicious sexual economy, exist only to provide pleasure for the dominant Cocks. La cazzaria also provides a more concrete example of a shamefully passive older partner in the story of Brother Paolino, “a friar about 42 years old,” who is severely injured when he is buggered by Brother Angelo, who could not find any younger men to have sex with. In most cities, convicted passive partners were treated more harshly than active ones. In Venice, however, the legal penalties were harsher for the active partner, as he was perceived as being the aggressor, and guilty of misusing his masculine prerogatives.

The hierarchical form of homosexual relationships characteristic of the period has often been seen as following a humanist, student-teacher model. A pervasive cultural linkage between humanist pedagogy and educational pederasty has been traced by Leonard Barkan, who argues in Transuming Passion: Ganymede and the Erotics of Humanism (1991) that the involvement of humanism in civic politics is marked from the beginning by the metaphor of pederasty. The “first rhetorician of government,” Dante’s mentor Brunetto Latini, appears in the Inferno as a sodomite. On a more general level, the Socratic relation between teacher and student carried with it in the Renaissance the same connotations of the corruption of youth that it did in ancient Athens. Possibly “the first proper usage of the term umanista in the Italian language” comes in a letter from Ludovico Ariosto to Pietro Bembo, which claims that most humanists are sodomites, and jokingly advises that if one sleeps next to a poet, “e gran periglio/ a vogierli la schiena” (“it is a great peril to turn one’s back to him”).

Although humanism and sodomy were often linked in the popular imagination, hierarchical homosexual relations between men were found at all social levels, and were in fact broadly characteristic of Mediterranean culture over a period of several thousand years. Nonetheless, in La cazzaria, sex between men is understood and praised as an elite practice, ideally suited to the academic environment that generated the dialogue.

In La cazzaria, the elitism of sodomitical sex comes in part from its rejection of the female. Throughout the dialogue female bodies are represented as physically and socially inferior to male ones, and sex with women is seen as a poor alternative to sex between men. While the penis is praised as “the most perfect and necessary of all created things,” female genitalia are valuable because they are “the cause of … so many pleasures for men.” And despite Arsiccio’s lavish—and ironic—praise of the female genitals as being liberal, generous, vast, and benign, he makes it clear on several occasions that Assholes are to be considered superior to Cunts. Female genitals are said to smell of shit (a failing the anus is oddly never charged with in the text), and Arsiccio repeats the traditional notion that menstrual blood is toxic: “this blood is so noxious to everything and greatly harms anything that it touches, because it still retains the nature of the original poison.”

The anus, on the other hand, is highly praised: “the asshole is the most honored among all the necessary things of life.” While some of this praise is clearly ironic, the dialogue is nonetheless quite serious in its celebration of anal sex. Arsiccio is certainly open about his own preferences: He contends that the asshole is the most precious part of the body, and declares that “ambrosia and nectar are nothing but the sweet tongue of a beautiful young man and the profound secret pleasure that is to be found in his soft delicate asshole.”

Arsiccio’s dialogue is always about power as well as pleasure, and the text’s celebration of sodomy is closely related to the erotic hierarchies and power struggles which mark Arsiccio’s fable of the body politic. La cazzaria attempts to inscribe sodomy as a discourse of mastery in a Republic of Assholes and Cunts ruled by an oligarchy of Cocks. In Arsiccio’s fable, being powerful is equated not just with having a penis, but with being a penis. The power of the Cocks comes from their ability to exploit others for their own pleasure. Nino Borsellino’s* contention that “the phallocracy of La cazzaria is not a destructive power, but rather a principle of energy that aims to regulate the relationship of public and private forces” ignores the extent to which phallic power in the dialogue is always aimed at imposing its pleasure on others, often by inflicting pain. From the torn asshole of Brother Paolino, to the “wounds” inflicted on the rebellious Cunts, phallic pleasure in La cazzaria is marked with a trail of blood.

But for Arsiccio, power is not merely sexual; it is intellectual. In La cazzaria knowledge, power, and sexual pleasure are all equated. Eroticism is understood ultimately as scienza, what Arsiccio calls “the science of fucking” and the “secret acts of sodomy.” This mysterious and hidden knowledge of the natural world is a precious commodity, and Arsiccio believes that—like Latin—it should be available only to a sophisticated elite. But such knowledge is always practical, not abstract. After all, the primary motive for Arsiccio’s eloquent exposition of erotic philosophy, science, and mythology is the seduction of the passive, younger (and suggestively named) Sodo.

La cazzaria records Sodo’s initiation into this elite, an initiation which—as is hinted at several points—will culminate in his being buggered by his mentor. Sodo is not entirely naïve about his role. Although he may initially be disdainful of sexual knowledge and woefully ignorant of the philosophy of the body, he is not an inexperienced pupil. Of the monk who tutored him, Sodo says, “I know he is learned in the asshole. He studied mine so much that I’m sure he knows all about it that there is to know.” The dialogue begins with both interlocutors in an undescribed location, then moves to Arsiccio’s room. At the midpoint of the dialogue the two begin to drink wine, and the text ends with both in bed, with Arsiccio saying they ought to stop talking and let the Cocks, Cunts, and Assholes alone, because they may well do some “good thing” on their own which will give ample matter for discussion the following night.

The dialogue’s reader, of course, is initiated along with Sodo. In the framing fiction that introduces the dialogue, Il Bizarro, another member of the Intronati, finds the text of La cazzaria in Vignali’s study. The framing fiction positions the dialogue as a shared secret, which will be passed around clandestinely from one member of the Academy to another. Only by keeping the text secret will they be able to read and learn more. “Above all,” Il Bizarro stipulates, “be sure that no one else sees it but you, because, if Arsiccio knew of this or heard about it … he would be so angry that he would … never again permit me to enter his study. … But if he doesn’t notice this one is missing, I hope to send you more of the same in a similar way.” This promise is, of course, addressed as much to the reader of the text as to the Archintronato.

The dialogue’s reader, of course, is initiated along with Sodo. In the framing fiction that introduces the dialogue, Il Bizarro, another member of the Intronati, finds the text of La cazzaria in Vignali’s study. The framing fiction positions the dialogue as a shared secret, which will be passed around clandestinely from one member of the Academy to another. Only by keeping the text secret will they be able to read and learn more. “Above all,” Il Bizarro stipulates, “be sure that no one else sees it but you, because, if Arsiccio knew of this or heard about it … he would be so angry that he would … never again permit me to enter his study. … But if he doesn’t notice this one is missing, I hope to send you more of the same in a similar way.” This promise is, of course, addressed as much to the reader of the text as to the Archintronato.

That much of the “knowledge” provided by Arsiccio is entirely fanciful and quite ridiculous does not diminish the seductive power of the text and the knowledge it offers. By making genital organs speak in a fable that is itself part of a discourse of seduction, La cazzaria points ultimately at the eroticism of discourse, particularly the elite, humanist discourse that promises to reveal hidden truths and to make the natural world speak. When Cocks, Cunts, and Assholes speak, they give a lesson in humanist civics. Sexual pleasure is conflated with textual pleasure, and there are hints that textual pleasure, identified as it is with the elite, all-male sodomitical world of the Academy, may well be superior. Il Bizarro is able to get his hands on the text only because Vignali goes out to bring him a servant girl to have sex with. It is typical both of La cazzaria’s elitism and its celebration of textual pleasure that after having had the serving woman, Il Bizarro admits that he much prefers the book.

The open homoeroticism of La cazzaria was provocatively dangerous even in the 1520’s, in the years before the Sack of Rome and the collapse of Sienese political independence. As the century progressed such discourse became all but impossible. The rise of a vigorous Counter-Reformation Church and the control of Italian politics by the militantly Catholic Hapsburgs resulted in much tighter controls both on literature and on behavior. The cultural change within the Academy of the Intronati itself can be seen by comparing La cazzaria with Alessandro Piccolomini’s 1539 dialogue, La Raffaella.

After Vignali’s departure from Siena, Alessandro Piccolomini (not to be confused with his kinsman Marcantonio Piccolomini, La cazzaria’s Sodo) emerged as the Intronati’s leading author. La Raffaella is his most sexually outrageous text, and it was sharply criticized on publication. Like La cazzaria it is a dialogue between a young innocent and an older, more experienced person, and the older person gives the younger instruction on sexual matters. In La Raffaella, however, the speakers are both female, and the advice given by the elderly Raffaella to the youthful Margarita is all concerned with how Margarita can make herself more attractive to men and have successful affairs. The dialogue is a conduct book for adultery, and its frank encouragement of extramarital sex for young women led to its condemnation. But compared to La cazzaria, or to Aretino’s Dialogues for that matter, it is an extremely mild text. There is no description of sexual activity whatsoever, and long sections of the dialogue dwell on such matters as the best recipes for facial ointments. Perhaps more importantly, the illicit sexual activity the dialogue advocates is much less subversive than either the sodomy of La cazzaria or the predatory prostitution of Aretino’s Dialogues. Even the adultery advocated by Piccolomini is not promiscuity, but the utter devotion of a young lady to a man who is not her husband. It is in many ways an idealistic continuation of the old fictions of courtly love. All the same, La Raffaella was considered a subversive and even dangerous text, and that such a traditional text was thought of this way provides a useful index of just how shocking La cazzaria must have been.

* Nino Borsellino. Rozzi e Intronati: Esperienze e forme di teatro del “Decameron” al “Candelaio” (1974).

Ian Frederick Moulton, author of Before Pornography: Erotic Writing in Early Modern England, teaches English at Arizona State University.