for American Scholar.

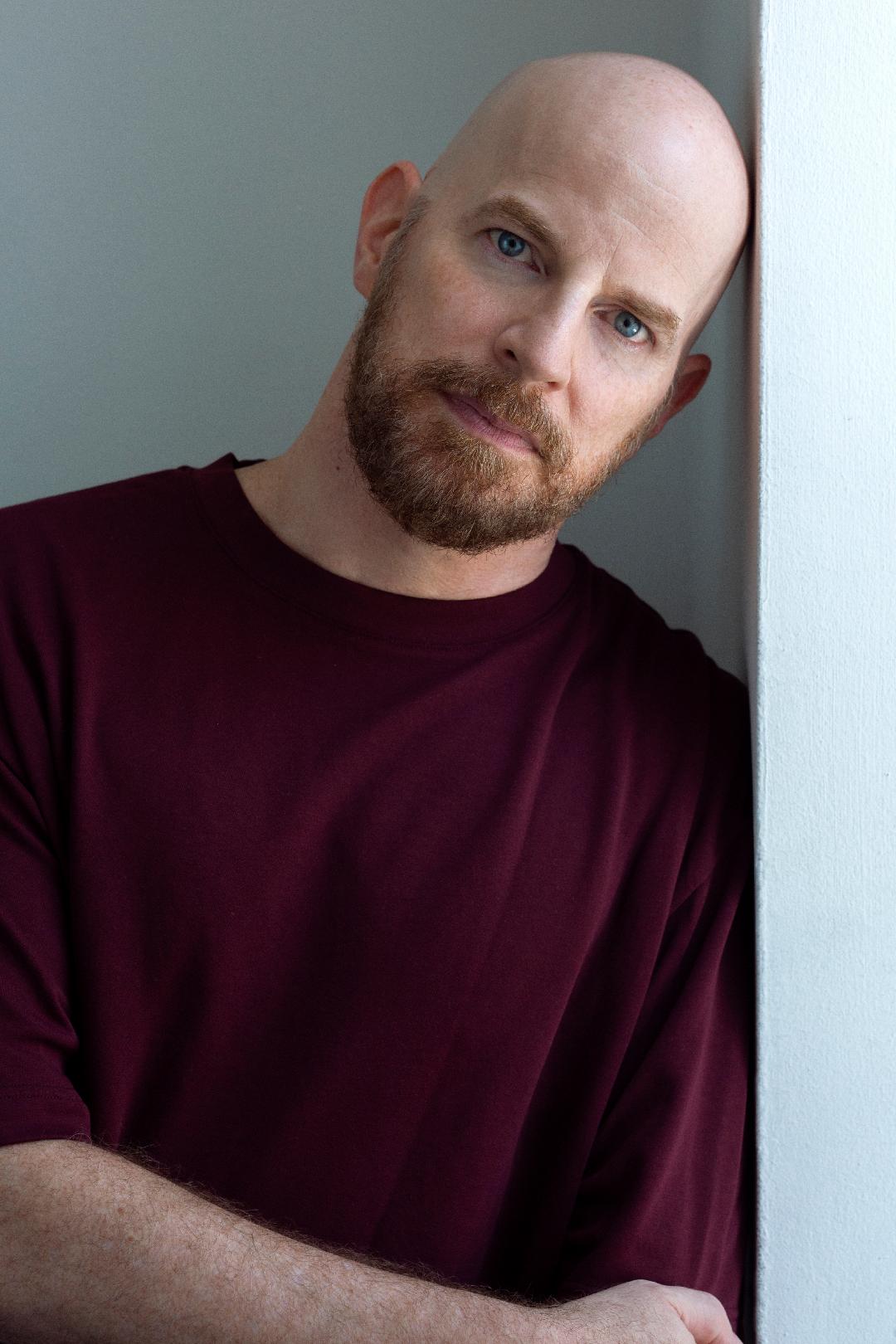

PATRICK E. HORRIGAN is a writer exploring the effect of art on individuals, beginning with his memoir Widescreen Dreams: Growing up Gay at the Movies (1999), and continuing with the novels Portraits at an Exhibition (2015) and Pennsylvania Station (2018). He has also written a play and essays, and is co-host of the recurring variety show Actors with Accents. He previously taught literature at LIU Brooklyn.

The title of Horrigan’s new novel, American Scholar, refers to the Harvard professor and founder of American Studies, F. O. Matthiessen, about whom the central character, James, has written a successful novel. Matthiessen was secretly gay, in a loving relationship, and ended his life in suicide. The novel connects James to an unsent letter written in the 1980s, sending him back to that decade and a passionate love affair, remembered in what’s described as a “hallucinatory” dark night of the soul.

This interview was conducted in written exchanges online.

Charles Green: American Scholar talks much about F.O. Matthiessen, the 20th-century academic who inspired American Studies. What drew you to him?

Patrick E. Horrigan: I first encountered Matthiessen in a graduate school American literature seminar. The professor recommended his American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman (1941) as a foundational text in American Studies and necessary background for understanding 19th-century American literature. The book’s seductive fusing of America and Europe captivated me. Its thesis was equally captivating: that the very best of American literature was produced in the mid-19th century, including Melville’s Moby-Dick, Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, Thoreau’s Walden, and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

I became even more fascinated by Matthiessen himself, discovering that he killed himself in 1950 at 48 years old, that he was a socialist when the Cold War demonized the Left, that he was gay when gay life was heavily persecuted, that he was in a long-term relationship with a visual artist twenty years his senior, and that he suffered from mental illness. Piecing together his life story, I found it moving. I was particularly riveted by a collection of letters to his partner, Russell Cheney, which was published several years earlier. At the time, I had recently come out and was just building a life in New York as an openly gay man. I had just entered graduate school and was beginning an academic career. Matthiessen seemed a kind of role model, and yet his life ended in tragedy. I wanted to understand what happened to him. I was also dating a man much like Matthiessen—a budding scholar of gay life and popular culture, a socialist suffering from suicidal depression. I was struck by this coincidence in my personal and intellectual life and wanted to understand why I seemed drawn to a certain type of self-destructive gay intellectual. This was the seed for American Scholar.

PEH: My books draw upon my academic training and sometimes feature intellectuals, but they’re not “academic books.” I’ve always been passionate about art—painting, music, film, architecture. But I’m fascinated by the encounter between the individual and the work of art and what the individual brings to this encounter. All my books feature this encounter between the perceiving subject and the art object. It’s here where I find stories about people and their encounters with art and explore how those encounters shape their lives, for better and worse. In American Scholar, Jimmy, an English PhD student, pursues his interest in American literature and Matthiessen to the detriment of his relationship with his boyfriend. In Portraits at an Exhibition, Robin attends an exhibition of Renaissance portraits to distract himself from anxiety over a recent, risky sexual encounter. He filters his perception of the paintings through his fears and hopes. In Pennsylvania Station, Frederick becomes involved in the effort to save New York’s Penn Station from demolition, but his commitment to preserving the past has dire consequences in his personal life, where changing is more urgent than living in the past. These are a few examples of how my work dramatizes the relationship between individuals and art in a way that, I hope, brings excitement to the life of the mind and heart.

CG: Pennsylvania Station takes place in the early 1960s, while parts of American Scholar are set in the late ’80s, with many references to the early and mid-20th century. Are there connections between these eras and our own time?

PEH: History is intrinsically interesting. It helps us measure ourselves and our present moment and helps us see ourselves clearly. I enjoy studying history and trying to represent the past. In Pennsylvania Station, what attracted me to the early 1960s was that it’s the moment before sexual liberation, before Stonewall and everything that flowed from that explosive event—and yet everything leading to Stonewall is contained therein. The two main characters, Frederick and Curt, represent two different stances toward the gay liberation movement. Frederick is a mostly closeted middle-aged man who lives his life under the radar. Curt is an out young man and activist who becomes increasingly committed to gay rights causes. But they love, need, and admire each other, so the lines dividing them are not fixed. In some ways this period is both more conservative and more radical than our own when it comes to the struggle for lgbtq rights.

In American Scholar, the narrative switches between the late 1980s, during the worst years of AIDS, and 2016 on the eve of the presidential election. In one passage, James considers the difference between life in the late 20th century and in the early 21st, about the revolution in technology and the political changes we’ve lived through in that short period. Life in the ’80s and ’90s throws life in this century into relief. In Portraits at an Exhibition, Robin looks at paintings from the Renaissance and imaginatively enters their world. The past contains potentially life-saving information for him if he could only access it, but he’s blind and deaf to it. In my memoir Widescreen Dreams, I analyze movies I loved as a child in the 1960s and ’70s to understand how those films and the culture they came from helped shape me. Again, it’s exploring the past that sheds light on the present. There’s always a connection between the past and the present, but we need to inhabit the past in a way that it speaks to us. Fiction seems uniquely poised to let us do that.

CG: Your first book, Widescreen Dreams, was a memoir. What prompted you to write fiction?

PEH: After Widescreen Dreams, I started work on another memoir exploring my interest in Matthiessen and my relationship with a young man who resembled Matthiessen in crucial ways. I wanted to understand myself and my attraction to a kind of self-destructive gay man. I wasn’t satisfied with the book. It lacked a center of gravity, and I was especially dissatisfied with the opaque picture of myself that emerged. I was in my early thirties looking back on my early twenties, so perhaps I was still too close to those events.

At that time, I was fascinated by portraits of men. Whenever I went to a museum, that’s all I wanted to look at. I realized there was a project in that, so I initially thought of writing a series of essays on portraiture. But I wanted to be as intimate as possible with the portraits. I didn’t know what that meant, only that I didn’t want to write from an academic distance. Then I had a fantasy about a young man in a gallery looking at a painting and another man looking at this young man. Then I added a museum guard looking at both. A story seemed contained within that network of gazes. That’s how I decided to approach the topic, and this became my first novel, Portraits at an Exhibition.

Charles Green is a writer based in Anapolis, MD.