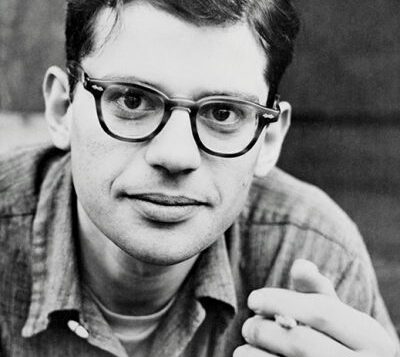

IN 1949, more than five years before writing his landmark poem “Howl,” a 23-year-old Allen Ginsberg was for eight months a patient at the New York State Psychiatric Institute (PI), where he got some much-needed help in the form of psychotherapy. From this hospitalization he took experiences and insights that would eventually find their way into “Howl,” and through this and other revolutionary poems, he helped to humanize both madness and psychiatry.

Ginsberg’s admission to the hospital had followed a scandalous car crash and arrest that made The New York Times. The alternative could have been a stint at Rikers, but a supportive letter from cultural historian Jacques Barzun, one of his Columbia professors, and a deal with the prosecutor sent him to PI instead. At the time, he had been having visions, and there was concern that he was becoming psychotic, like his mother, who had been in and out of psychiatric hospitals and diagnosed with schizophrenia.

At PI, Ginsberg’s behavior came under the scrutiny of the psychiatric practices of the day. On several occasions, he said that his main problem was his homosexuality, which he hoped to change. His sexual orientation was regarded in part as homosexuality and in part as a symptom of “pan-sexuality,” the sexual attraction to a person of any sex or gender. According to the diagnosis of “pseudo-neurotic type schizophrenia,” which Ginsberg had been assigned by his doctors, pan-sexuality was one of a number of defense mechanisms guarding against an underlying psychosis, which he had probably inherited from his mother Naomi. The psychiatrists urged him to give up such behavior and to try being with women, though they didn’t push too hard for fear that he might spiral further into psychosis. He partially complied, saying he would have a threesome with a male friend and a woman as a way to transfer his intimacy from him to her.

I was able to review these records when, in the 1980s, Ginsberg himself gave me permission to do so as part of my research for my book about his mental illness and its impact on his work. The mid-century psychiatrist’s formulations could not see his sexual attraction to men as other than a symptom of a psychiatric disorder. Nevertheless, some of the PI psychiatry residents on staff were sympathetic to gay men and lesbians. One such resident met with Ginsberg’s father Louis and instructed him to accept his son’s homosexuality as part of his illness. Ginsberg told me that he was very grateful for this bold action, which, while it didn’t free him up to embrace his homosexuality, did make a positive difference in his relationship with his father.

In his psychotherapy sessions at PI, Ginsberg offered his own hypothesis as to what led him to be gay: his mother’s delusional, inappropriately seductive behavior had turned him off to female sexuality. His willingness to offer such an explanation reflected his insecurity about his sexuality and his attempt to accommodate himself to the intolerance of the times. To the psychiatrists, his mother had given him a “genital shock,” an archaic term referring to a child’s exposure to adult sexuality. Both he and his therapists were limited by the existing theories about the impact of a parent’s mental illness on a child. This was decades before our current understanding of trauma and the removal of homosexuality as a mental illness.

For much of Ginsberg’s childhood, his mother Naomi had experienced delusions, hallucinations, agitation, and suicidal ideation. She had frequent, long hospitalizations. When she was home, Ginsberg was her primary caregiver. After his parents divorced, he was the primary family member left to make decisions regarding her care. Naomi, who was herself a victim of child sexual trauma, engaged in nudism and sexually provocative behavior with her son (which he called “making sexual demands”).

A side benefit of Ginsberg’s psychiatric treatment is that he learned to curb his grandiosity. He couldn’t just proclaim himself to be the greatest poet of his age; he had to back it up with work. He learned not to tempt fate by associating too closely with others’ criminal behavior. With the therapists’ help, he was able to distance himself from the visions that were bringing him close to psychosis. Beyond the treatment itself, being in the “madhouse” was a valuable experience for Ginsberg. He learned to break down his dichotomous view of sanity and insanity, to see the humanity of persons in the grip of madness, to see its potential for both liberation and injury. He also came to regard himself as uniquely positioned to understand madness and psychiatric treatments.

Ginsberg was relieved that upon his discharge, the psychiatrists told him he was not going to become schizophrenic like his mother. As it turned out, he had among the best outcomes for those diagnosed with pseudo-neurotic type schizophrenia. He would have to wait several more years before his psychotherapist in San Francisco, Dr. Philip Hicks, went much further in telling him to go ahead and live with his new friend, Peter Orlovsky, and devote himself to writing poetry.

From its famous first line—“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness”—“Howl” bears witness to both the liberating and destructive potential of madness. The poem then confronts the institutions that confine and sacrifice the vulnerable, and finally expresses solidarity with those in the grip of madness. It encourages and embraces madness, despite the risks involved, as a potential path to freedom.

Ginsberg never truly recovered from the loss of his mother to mental illness, prolonged confinement, lobotomy, and early death. He was tortured by the role he played in signing consent for her lobotomy and sending her back to the psychiatric hospital. He made it clear that he lived every day with the pain caused by these experiences. Throughout his adulthood, he had a tendency to welcome madness into his life and then try to take care of it. His lifetime partner, Peter Orlovsky, was prone to mania and drug abuse. Ginsberg also had a tendency to choose straight men as partners.

Ginsberg never did go mad like his mother, though he never got the therapy he needed to relieve himself of the guilt, trauma, and moral injury of having done such harm to her. To the psychiatrists, Ginsberg’s homosexuality was a symptom of mental illness. In the poet’s hands, the freedom to have straight or gay sex, and to talk openly about either, became essential components in the message about liberating madness that he was trying to spread. In this way, he incorporated but turned around the psychiatric dogma of the day and made it part of the revolution he led with his poems, helping to open minds and the culture about mental illness and homosexuality.

Stevan Weine is the author of Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness (Fordham, 2023).