ARE HOMOSEXUALS inherently maladjusted? It was a question whose answer was so self-evident that psychiatrists in postwar America scarcely raised it at all. As members of a profession, they may have been obsessed with figuring out how to identify homosexual traits or to root out secret desires, but the question of whether homosexuals were mentally ill was not asked, and could not be asked, so long as it was defined as itself a variety of mental illness or as a symptom of a broader syndrome. What’s more, it was official: there it was in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), the bible of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which included homosexuality as a “sexual deviation” along with pedophilia and sexual sadism. The prevailing view was expressed by a leading psychiatrist of the day: “When such homosexual behavior persists in an adult, it is then a symptom of a severe emotional disorder.”

Someone needed to point out the naked emperor in the room: the fact that the inclusion of homosexuality as a mental illness by the psychiatric establishment was based on an untested assumption, one that placed homosexuals under their auspices, to be sure, as if the mere inclusion of homosexuals in the DSM rendered such people “maladjusted” (the term du jour for “mentally ill”). It was Evelyn Hooker, in a landmark paper published in 1956, “The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual,”* who pointed out that the APA’s assumption about homosexuality as a “mental illness”—indeed its assumption of homosexuality as a psychiatric concern—was unwarranted. It was perfectly possible to test this assumption by treating homosexuality and “adjustment” as separate variables that could be empirically measured and statistically compared.

Once Hooker had pulled the two concepts apart, what she found was that the standard assumption was far from ironclad. Her research played no small role in the ensuing debate, which simmered at first and came to a boil after the Stonewall Riots of 1969, culminating in the removal of homosexuality from the DSM in 1973, which all at once freed millions of Americans from the stigma of mental illness.

§

Hooker’s improbable life journey began in 1907 in North Platte, Nebraska, where she excelled in school and was encouraged by her teachers to attend college out-of-state. Off she went to the University of Colorado, where she majored in psychology, remaining in Boulder to earn a master’s degree in the same field. From there she made her way to Johns Hopkins University, where she was one of the first women to earn a doctorate in psychology, in 1932. Next, her journey brought her to the Berlin Institute of Psychotherapy, where she lived with a Jewish family and witnessed firsthand the rise of Adolph Hitler, which became an important catalyst in her lifelong commitment to social justice. Returning to the U.S. a few years later, she made her way to UCLA (after a detour or two), where she worked as a research associate and later as an instructor.

Up to this point, her work had been guided by behavioral psychology, and she’d shown no particular interest in homosexuality. It was while teaching a course at UCLA that she was approached by a precocious student named Sam From, who confided to Hooker that he was gay and wondered whether, in her opinion, this meant that he was mentally ill. They became pals; From introduced her to his circle of gay friends, which included Christopher Isherwood and Stephen Spender; he took her around to L.A.’s gay bars and clubs. Getting to know these highly successful gay men, Hooker began to question the pathological model of homosexuality. From urged her to investigate, saying that it was “her scientific duty to study people like us.” Having been bullied as a kid in Nebraska (apparently for being freakishly tall) and having witnessed the rise of fascism in Europe, she decided that this would become her life’s work.

Hooker launched her research at a time when psychiatry was riding high, not only as an academic discipline but as a clinical practice and even as a basis for social engineering. This was the age of mass institutionalization of “the insane,” involuntary commitment of persons deemed “certifiable,” and the widespread use of various procedures designed to “cure” homosexuals. The latter included electroshock, aversion therapy, hormone injections, and lots of time on “the couch.” (U.S. doctors, unlike those in the U.K., largely avoided chemical castration.) Given the power and prestige of the psychiatric establishment, it’s remarkable to think that Evelyn Hooker, an obscure psychologist—not even a psychiatrist—and a woman at that, was able to singlehandedly challenge a mainstay of the DSM and rock American psychiatry’s world.

How did she do it? The genius of Hooker’s approach is that she didn’t attempt to refute the DSM’s position on its merits or challenge its methods of diagnosis and treatment. Rather than try to settle the question of whether homosexuals really were maladjusted, she decided to test the psychiatrists who were rendering this diagnosis on their ability to recognize a homosexual using the standard tools of the psychiatric trade. If homosexuals were by definition maladjusted, then surely any competent psychiatrist armed with a detailed profile of a patient’s overall level of adjustment could spot a homosexual with ease.

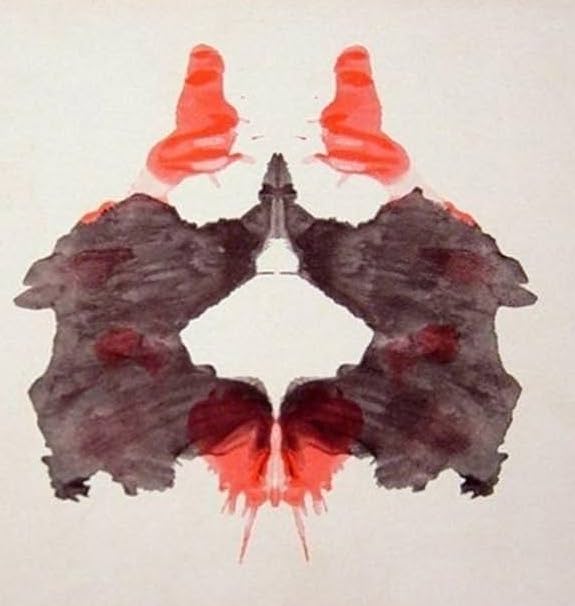

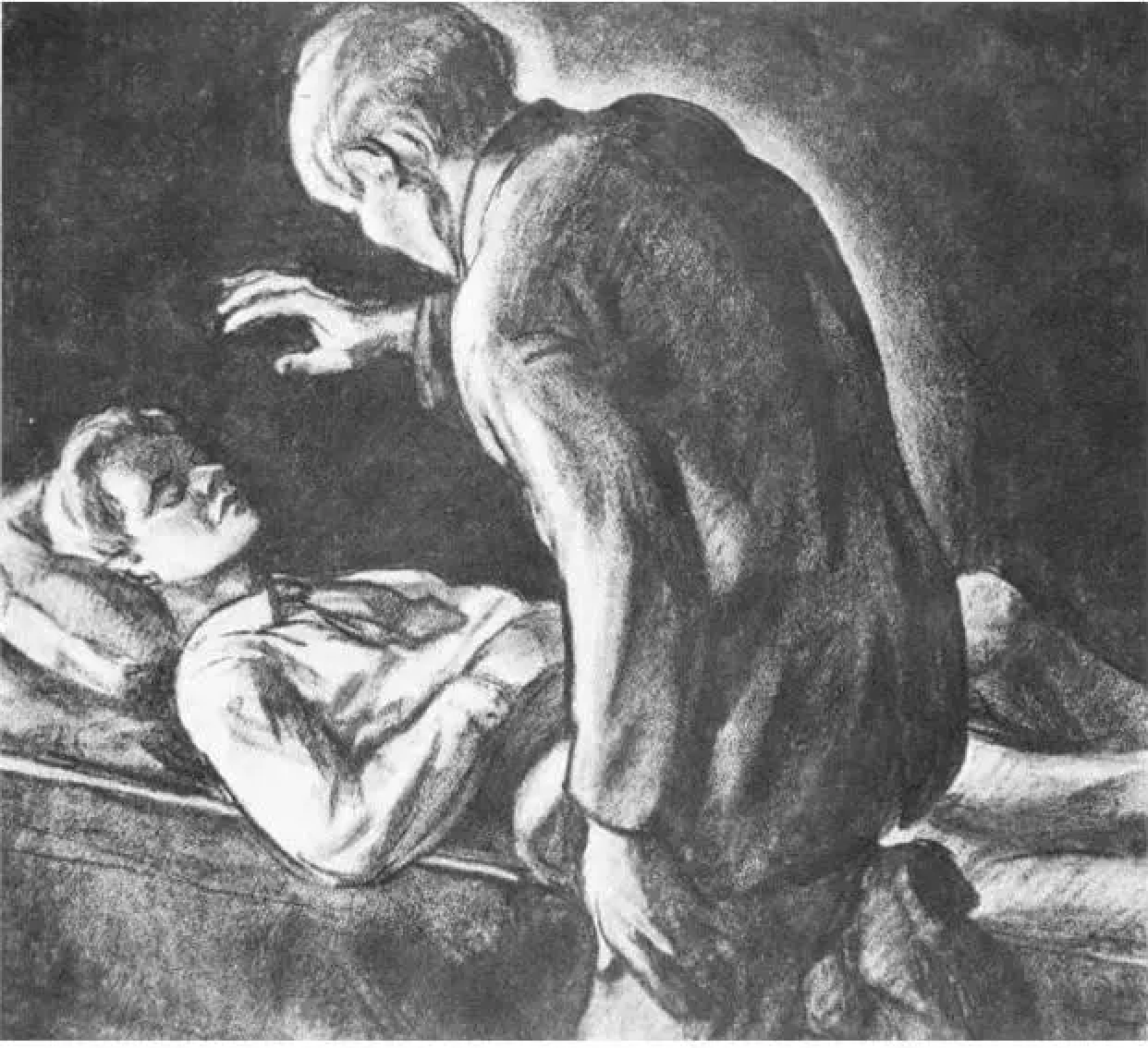

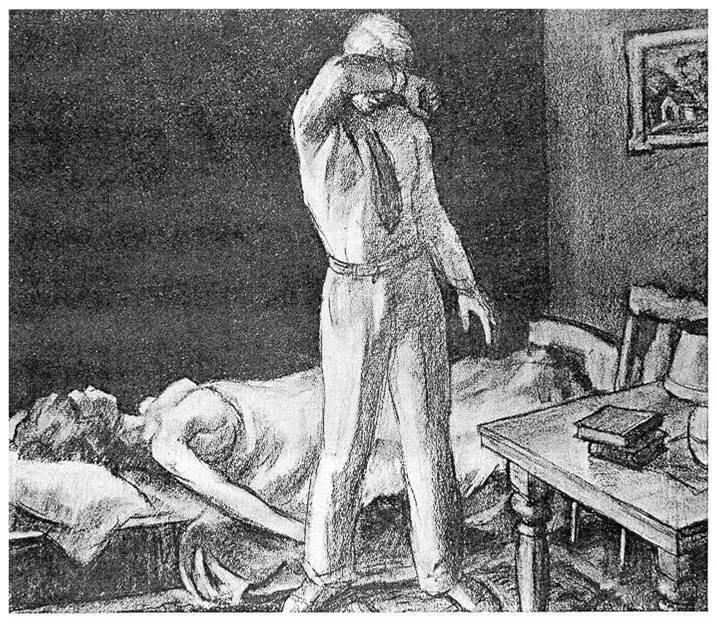

The major diagnostic tools at this time were a handful of “projective tests,” of which the Rorschach was the most important, typically supplemented by the TAT (Thematic Apperception Test) and MAPS (Make-A-Picture-Story). All three involved the presentation of a standardized set of pictures—abstract inkblots for the Rorschach, drawings of people alone or in groups (typically in pairs) for the other two—which had been used by thousands of practitioners over the years to assess the mental health of both clinical patients and experimental subjects. Indeed, one is struck by the authority invested in these tests and the extent to which their meaning was relied upon for highly detailed analyses of psychiatric symptoms. Nor did Hooker question their usefulness, choosing instead to accept the proposition that they were reliable tools with which to assess levels of adjustment. But could this assessment really be used to determine if someone was gay?

To find out, Hooker developed a sample of sixty individuals, all men, ranging in age from 26 to 57. She was very careful in her selection of thirty homo- and thirty heterosexual subjects, avoiding anyone who had ever sought psychological help or been incarcerated or disciplined in the military.** To ensure that the two subsamples were comparable, she set up a system of matched pairs based on age, IQ, and level of education. The sixty subjects were put through the rigors of the three projective tests, which called upon them to describe in a few sentences what was going on in the ambiguous scenes. These descriptions were fed to three experts in Rorschach interpretation, who were told in advance that half of the subjects were hetero- and half homosexual men. Their assignment was twofold: to provide an overall assessment of each subject’s level of adjustment using a standard five-point scale (with 1 the “Top” rating and 5 the “Bottom”); and to determine which subject in each pair was homosexual based on these assessments.

Not to prolong the suspense, the outcome was striking and clear-cut. While the judges showed a high degree of consensus in rating the sixty men’s level of adjustment based on the five-point scale, their ability to identify the hetero- and homosexual subjects was no better than chance. Hooker’s conclusion: “there clearly is no connection between pathology and homosexuality.” One reason for her confidence is related to a feature of the Rorschach itself. In addition to revealing a subject’s overall level of mental health, the Rorschach was regarded as the most effective test in the psychiatrist’s quiver to determine if a subject was homosexual. Based on a modest body of research, a number of “signs” had been identified, such as the tendency to see buttocks, sex organs (either male or female), or feminine clothing in the inkblots. In her review of this literature, Hooker showed that all past studies were deeply flawed, typically because the rater was working with a sample of men who were specifically selected for their homosexual orientation, in some cases men who had been diagnosed as mentally ill.

To get a better idea of where these “signs” may be coming from, consider a couple of the cards that were taken to separate the men from the gay men, numbers II and IV. For those unfamiliar with the standard set of fifteen Rorschach images, let it be stated that the inkblots were not just random shapes; they were designed to get a reaction. Card II would seem to show two figures facing each other with certain body parts abutting; their sameness could suggest a same-sex interaction of some kind. Card IV seems tailor-made to elicit a phallic association—which indeed it often did. The only problem was that the gay and straight subjects were equally likely to perceive something along these lines.

While her statistical analysis of the difference, or lack of one, between the homo- and heterosexual subjects is convincing, Hooker’s best evidence is perhaps the lengthy quotations she provided from the judges’ reports. One is struck here by the confidence bordering on arrogance of these psychiatric evaluations, which flatly affirm that one man has dependency needs, another lacks impulse control, a third is adept at handling aggression. (The long arm of Freud is clearly visible here.) But when it came to pegging the subjects’ sexuality, their language turns to perplexity. Commented Hooker on these attempts: “As a judge compared the matched protocols, he would frequently comment, ‘There are no clues’; or, ‘These are so similar that you are out to skin us alive’; or, ‘It is a forced choice’; or, ‘I just have to guess.’”

These comments are especially revealing of the kinds of stereotypes that supported the assumption of homosexual pathology. Hooker noticed, for example: “When careful examination failed to reveal anything distinctive, the judge assumed that the more banal or typical record was that of the heterosexual, an assumption which was sometimes false.” The tendency to label the less banal profile as homosexual clearly reflects the belief that gay men’s departure from the norm was a pervasive feature of their personality, and that this departure veered toward hysteria, exaggerated affect, neurosis, and the like (which still beats banality!).

Elsewhere Hooker pointed out that gay men in general were thought to exhibit symptoms of schizophrenia, often of the paranoid variety. Hooker was among the first to point out that paranoia could be a perfectly normal response to anti-gay persecution or the fear of exposure. Nevertheless, she found that there was no particular connection between homosexuality and psychotic symptoms. Even when the raters were able to correctly ascertain that a subject was gay, they were forced to admit that this condition often did not coexist with any other pathology.

§

After the Rorschach came the TAT and MAPS, which were administered together and provided an additional window into each subject’s psyche. Unlike the inkblots, the TAT and MAPS present recognizable images of people alone or in groups, some in intimate situations that may be more likely to elicit revealing comments or even “confessions” of a kind. In short, many of the gay subjects outed themselves either openly or implicitly. Thus the second part of the Rorschach section—identifying the men’s sexual orientation—was suspended for the tat-maps section. The judges were still asked to evaluate the subjects’ overall level of adjustment based on the projective narratives.

Given the assumption that someone who’s gay is ipso facto mentally ill, one might have expected a weight to drop on these subjects’ adjustment scores, but such was not the case. Even with this knowledge in hand, Hooker reported, when the raters assessed the sixty subjects using standard criteria for adjustment on several dimensions, the two subsamples differed to no significant extent. For the record, the judges were able to identify around a third of the gay subjects with confidence, “while the remaining two-thirds cannot be easily distinguished,” Hooker reported.

Noting the tension in their own evaluations, many of the judges’ comments are priceless. One judge marveled that this is “the most heterosexual-looking homosexual I have ever seen.” Another describes a subject whose “impulse control is very smooth” and whose “aggressive impulses are expressed in phallic gratification. … He must be heterosexual.” And yet, he was not. Another subject was described as “thoroughly immersed in the homosexual way of life, but apart from this I see no particular evidence of disturbance.” This comment hints at Hooker’s grand conclusion. After she has shown that homosexuality cannot be predicted by a general assessment of mental health or identified by a panel of experts, she concludes that sexual orientation can exist in isolation from other atypical characteristics. Her landmark article ends with the words: “If one assumes that homosexuality is a form of severe maladjustment internally, it may be that the disturbance is limited to the sexual sector.”

The importance of Hooker’s study lay not so much in debunking the assumption of homosexual maladjustment as in striking a blow to professional psychiatry’s confidence in its ability, or even its right, to talk about homosexuality at all. By choosing three judges with impeccable credentials, Hooker had demonstrated that even the most seasoned experts armed with detailed psychiatric profiles couldn’t pick out the homosexual men, many of whom turned out to be high achievers whose sexual orientation apparently did not diminish their ability to function as productive citizens. Hooker’s study raised the hitherto unthinkable possibility that sexual orientation may be an area where psychiatry really didn’t belong. It would be another fifteen years before the APA would officially delete homosexuality as a mental illness—a tacit admission that they’d been trespassing on foreign territory all along.

* Hooker’s paper was published in the October 1956 issue of The Journal of Projective Techniques.

** The critical role of sample selection becomes apparent in a 1958 paper titled “Male Homosexuality in the Rorschach” (The Journal of Projective Techniques), which includes a literature search of research comparing hetero- and homosexual populations. It was common practice to use prison populations or men recently arrested for homosexual activity or people in institutions for the mentally ill. Noted Hooker: “It therefore seemed important, when I set out to investigate the adjustment of the homosexual, to obtain a sample of overt homosexuals who did not come from these sources; that is, who had a chance of being individuals who, on the surface at least, seemed to have an average adjustment.”

Wendy Fenwick is an international writer based in Boston.