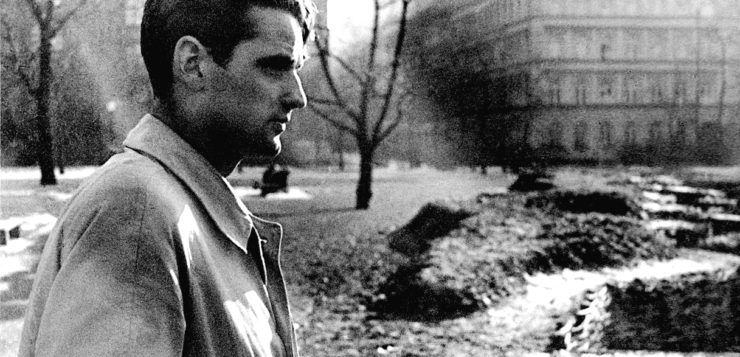

IN MANY STORIES about World War II, the German people are typically painted with broad strokes as a nation of committed Nazis. Not so well known on this side of the Atlantic are the stories of German soldiers and students who spoke out against Hitler. These were complicated heroes, challenging their country while being forced to serve it in a war they despised. They had to make difficult choices every day, juggling the demands of citizenship with those of living an ethical life. One of the most complex of these heroes was Hans Fritz Scholl.

Like many German children growing up in the 1930s, Hans Scholl (1918–1943) initially welcomed the rise of Hitler. He saw Hitler as a kind of savior who would lift Germany out of widespread poverty and unemployment. He and his siblings eagerly joined Hitler Youth, an organization that gave them opportunities to go camping and horseback riding, to participate in competitive sports, and to develop their leadership abilities. With his intelligence, charisma, and physical strength, Hans rose quickly up the ranks of Hitler Youth leadership.

But disillusionment would eventually set in. Hans and his friends were creative people who brazenly read banned books, and refused to be limited by the official Hitler Youth literature, symbols, and flags. So they organized, inventing their own name, making their own banners, and even printing their own stationery. And while these activities were clearly illegal, Hans and his friends were sufficiently protected by their middle-class “Aryan” status that they probably wouldn’t have got caught—if it weren’t for the fact that Hans fell in love.

Hans was sixteen when he began a relationship with fifteen-year-old Rolf Futterknecht during a camping trip in 1935. Raised as a Lutheran and deeply religious, Hans struggled with his feelings for his friend but found that he couldn’t resist them. Their sexual relationship lasted over a year, and after it ended, they remained close friends.

Radicalized by a Youthful Flame

By November 1937, Hans Scholl had put Rolf Futterknecht behind him. Now nineteen years old, he was dating his sister’s friend Lisa Remppis and training for the cavalry. Then, one day, his commanding officer received a “Very Urgent” request from the Gestapo to transfer Scholl to civilian status so that he could be charged and tried for paragraph 175 of the German criminal code, homosexual acts, for which they said Scholl was “urgently suspicious.” The Gestapo came to his barracks, questioned him, and then presented him with a signed confession by Rolf Futterknecht, who accused him of having seduced him into committing lewd acts while they had been in Hitler Youth.

It’s not entirely clear what led Futterknecht to denounce Scholl to the Gestapo. Perhaps it was to gain Nazi approval or be spared from similar charges. Another man Rolf accused of homosexuality was a close friend of the Scholl family named Ernst Reden, who was several years older than the other boys. It was known that Reden had romantic feelings for Scholl’s younger brother Werner, but no one knew about Scholl and Futterknecht. Thus Scholl could have claimed that his former friend was lying, but instead he assumed full responsibility, denying nothing. He even tried to protect Futterknecht from suspicion, saying that he should bear the blame since he had been the older boy (albeit by only a year and a half). Scholl said he often tried to stop, but couldn’t because of his “great love” for his friend.

Scholl was imprisoned in Stuttgart for seventeen days, through the end of December 1937, mostly in solitary confinement. He wrote a letter to his family, admitting to the crime he was charged with. Describing his struggles with his sexuality, he said: “I believed that I had washed myself clean by tireless work on myself.” He begged: “Please do not tell the siblings, except Inge.” Inge, the eldest Scholl child, kept it not only from her siblings, but from all of history, taking her brother’s secret with her to her grave. Whenever she told the story of Scholl’s 1937 arrest, she claimed it was because of “bündische activities”—membership in a banned youth group. It wasn’t until years after her death in 1998 that evidence of Scholl’s same-sex relationship was uncovered.

Despite the feelings of shame associated with his criminal charges, Scholl’s perspective deepened while he was in jail. He concluded that he hadn’t done anything wrong, writing to his parents: “Even if I can’t justify myself in open court, I can justify myself to myself.” He was beginning to trust his own conscience as his ultimate authority. Later, when other Germans were quick to sacrifice their will to that of the Führer, he would hold himself to a higher moral standard.

With the help of a lawyer and a recommendation from his commanding officer, Scholl was released from jail, pending his trial. His friend Ernst Reden was not so lucky; he remained in jail for over six months. At their trial on June 2, 1938, Scholl’s friend Reden looked so pale and thin that he was almost unrecognizable.

Reden was convicted of paragraph 175 and sentenced to time served. He now had a criminal record and was barred from studying at any university—an extremely painful loss. Scholl’s case met a more lenient end. The judge decided to close his case following a recent decision by Hitler to grant amnesty for bündische cases. After months of stress and worry, Scholl was able to walk out of the courtroom with no criminal record.

But returning to military life was not easy for him. “I keep a rosebud in my breast pocket,” he wrote on June 27, 1938. “You should always carry a little secret around with you, especially when you’re with comrades like mine.” The boy who had once commanded troops of Hitler Youth now found himself alone, bewildered by people’s excitement about the annexation of Austria (as he wrote to his parents on March 14, 1938): “I don’t understand people anymore. Whenever I hear all that anonymous jubilation on the radio, I feel like going out into a big, deserted plain and being by myself.” In letters, Scholl now seemed ambivalent or critical toward Hitler. His dream of becoming a cavalry officer was replaced by a dream of becoming a doctor. Once his compulsory service was behind him, he was overjoyed to be accepted into the University of Munich to study medicine.

There he made friends with a philosophy student named Hellmut Hartert. When war broke out in 1939, both men were drafted to go to France in a student company, where they shared quarters and often went on assignments together. They shared a small attic for most of 1940, despite the fact that it was uncommon for men to share a room. Though the level of their intimacy remains unknown, clearly they were very close, and when their friendship ended abruptly, it baffled the people around them.

In 1940, when Scholl and Hartert were in France, they were assigned to the same unit as another medical student named Alexander Schmorell, who became fast friends with Scholl. Schmorell was smart, witty, and anti-authoritarian, with conflicting loyalties to Germany and Russia, the country of his birth. He often had parties where friends would read their writings and discuss literature, and it was here that Scholl met Willi Graf and Christoph Probst.

As a teen, Graf had refused to join Hitler Youth. He and Scholl may not have had that in common, but they did share a deep love for God. Probst, one year younger than Scholl, was already married with two children. Probst’s stepmother was Jewish, and he objected to her being forced to wear the yellow star. Through friends like these, Scholl’s eyes were opened to the truth about the Nazi regime and the atrocities committed against Jews, Poles, and Russians. In May 1941, after years of working in the National Labor Service, Scholl’s younger sister Sophie joined him at the university. She embraced his circle of friends and felt they had a “good influence” on her brother, and would later come to play a role in the group’s resistance activities.

The Pamphleteers

In June 1942, after the Allies’ massive bombing campaign devastated German cities like Cologne, many Germans clung to patriotism even more fiercely. But Scholl and Schmorell did the opposite. Seeing that Germany was losing, they decided it was time to expose Hitler’s lies. They started to write anonymous pamphlets titled “Leaflets of the White Rose,” accusing the Nazi regime of mass murder and demanding its end.

Their first leaflet reproached their fellow Germans for surrendering their most precious gift, their free will, to Hitler, thereby becoming “an unthinking and cowardly mob.” Indeed, the German parliament had all too willingly ended individual freedoms after the Reichstag fire in 1933: “[E]very individual has been jailed in an intellectual prison after having been slowly, deceptively, and systematically raped.” But it wasn’t too late. Germans could stop this with “passive resistance” and perhaps save themselves from meeting the same fate as the people of Cologne.

Soon after that first leaflet was written, Scholl’s own father was reported to the Gestapo for calling Hitler “God’s scourge.” As his father awaited trial, Scholl spent all his waking moments writing, producing, and distributing leaflets. The second leaflet informed people that “since Poland was conquered, three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered in that country in the most bestial manner imaginable.” Scholl and Schmorell were probably listening to illegal foreign radio broadcasts, but also hearing from friends like architect Manfred Eickemeyer, who let the students use his studio when he was working in Poland.

Their third leaflet asked readers: “Has your spirit been so devastated by rape that you forget that it is not only your right, but your moral duty to put an end to this system?” They called for people to sabotage factories and to stop donating to the war effort. In the fourth leaflet, which Scholl wrote alone, he begged his fellow Christians to “attack the Evil One where it is strongest, and it is strongest in the power of Hitler.” He also stated that his goal was not just political, but spiritual: “[W]e seek to achieve a revival of the deeply wounded German spirit from within. However, this rebirth must be preceded by a clear confession of all the guilt the German nation has incurred. … We will not keep silent. We are your guilty conscience. The White Rose will not let you alone!”

After this impassioned closing, recipients were probably baffled when no more leaflets arrived for about six months. Scholl and his cohorts had been sent to Russia with their student medic company in July 1942. At a farewell party, Scholl showed some leaflets to a few other friends, but when asked if he knew who wrote them, he made only enigmatic replies. In Russia, Scholl tended to sick and wounded soldiers while taking shelter as best he could from the bombs. His sister Inge wrote that he often tried to reach out to poor people with small, personal gestures. She told of instances when he gave gifts of tobacco and chocolate to Jewish people he encountered. When Scholl and Schmorell came across the corpse of a Russian, just lying there, they dug a grave so the man could be buried with some dignity.

One of the few people he told about his activities was his girlfriend Traute Lafrenz, who happily helped with the White Rose leaflets. But their relationship didn’t last. She later told Dr. Robert Zoske that Scholl was plagued by problems which he kept “dreadfully secret,” and that they had no sex.*

In August 1942, Scholl’s father Robert was sentenced to four months in prison for his “God’s scourge” comment about Hitler. His mother asked Scholl to beg the court for clemency, thinking it would carry more weight coming from a soldier. But he refused, writing in his diary: “I won’t do it under any circumstances. I won’t plead for mercy. I know the difference between false pride and true.” Later that month, thinking about his father, he recalled his own time in prison: “There are things far worse than prison. It may even be among the best.”

In September, Scholl learned that his friend Ernst Reden had been killed fighting in Russia. Ernst gave his life for a country that had thrown him into prison and closed all doors to him because of his sexual orientation. Scholl was “hard hit” by that news. His sister Sophie was filled with anger too, and said now she would have to “avenge his death.” As soon as Scholl’s unit came home in November, he ramped up his resistance activities, taking them to a bolder and more dangerous level.

Sophie moved in with Scholl in December 1942, and if she wasn’t involved with the leaflets before that point, she was now. Scholl worked with her philosophy professor Kurt Huber to write a fifth leaflet. He began a campaign of networking with other young resisters who were friends of friends, in cities as far away as Berlin. He stopped using the “White Rose” heading and went with “Leaflets of the Resistance,” hoping it would look like resistance was springing up all over Germany. Throughout January 1943, Hans, Sophie, and their friends worked hard copying and distributing leaflets. On weekends, they took suitcases full of leaflets onto trains and carried them to towns around the country.

In February, Scholl, Schmorell, and Graf started painting anti-Nazi graffiti on buildings in downtown Munich and the university quarter. They always went late at night, and Scholl carried his military-issue gun for safety. They made a template that read “Down with Hitler.” Scholl painted the word “Freedom” in large letters above the doors of the university, using tar-based paint, which was very difficult to remove.

Often, after a night of mailing leaflets or painting graffiti, Scholl would stay with his girlfriend Gisela Schertling. (In Gisela’s case, they did have sex.) But first, he usually paid a visit to his friend Josef Söhngen, an older bookseller described by his family as gay. They drank wine and discussed literature and politics. The letters these two exchanged were not explicitly romantic but did explore the subject of love. Söhngen supported Scholl by storing leaflets and equipment in his cellar, but he cautioned Scholl against some of his riskier ideas, including the one that led to his capture.

On February 18, 1943, Scholl and his sister walked to the university carrying a suitcase full of leaflets. Recently, there had been student protests after a prominent Nazi official gave a very insulting and misogynistic speech. Scholl saw this and figured the student population was finally ripe for resistance. Along with the suitcase, he was carrying the draft of a new leaflet, one not written by Scholl but given to him by his friend Christoph Probst.

When they arrived at the university, Scholl and his sister placed leaflets under the doors of lecture halls, to be seen when students exited class. But it didn’t go as planned. In haste to get rid of their leaflets before the end of lectures, Sophie pushed a stack of leaflets from a balustrade on the level above. As papers scattered down to the floor of the atrium, a janitor saw the two pamphleteers and placed them under arrest. The Gestapo arrived quickly. As the two were led away, a crowd of students gathered to watch, and among them was Gisela Schertling. Scholl gave Gisela a coded message for his friend Alex Schmorell, which appears in the transcript of his interrogation: “Go home and tell Alex, if he’s there, he should not wait for me.”

Hans and Sophie Scholl were taken to Gestapo headquarters at Wittelsbach Palace in Munich. Before the Gestapo could get to Probst’s draft, Scholl attempted to tear it up and swallow it, but they extracted the pieces from him. Still, he claimed not to know the author. He and Sophie initially denied any knowledge of the leaflets, but they failed to convince their interrogators that Sophie’s empty suitcase was for picking up laundry. As their defense crumbled, they tried to keep silent about their friends’ involvement, but found they couldn’t ultimately spare them from suspicion, as they had already been given up by Scholl’s girlfriend Gisela Schertling.

Gisela Schertling’s parents were ardent Nazis. Scholl knew this, but still trusted her with his secrets. She told the Gestapo that Scholl often discussed politics with her. When they showed her the leaflets, she was appalled by them. Despite some gaps in her knowledge, she gave the Gestapo a lot of names and information, which they used to pry still more out of Hans and Sophie Scholl. Once again, the former had been betrayed by someone he loved.

Schmorell went on the run. Graf was quickly arrested, and so was Probst, once the Gestapo learned that he had written the pamphlet. There was soon enough evidence to convict the two Scholls and Probst of treason, so on February 22, 1943, a trial was held in the People’s Court with judge Roland Friesler presiding. Loyal Nazi Party members were invited to attend, but Scholl’s parents were forced out of the courtroom. With a booming voice, Judge Friesler called them traitors who had raised “a dagger for a stab in the back of the Front!” Scholl tried to explain that Probst was not responsible for any of the printed leaflets, but the judge told him he could either speak for himself or remain silent. After only three hours, Hans Scholl, 24, Sophie Scholl, 21, and Christoph Probst, a 23-year-old father of three, were sentenced to be beheaded.

As Scholl’s parents made their final goodbyes to him in the Stadelheim execution prison, his father told him how proud he was, and that Scholl would go down in history. Scholl gave his parents a tearful message to give to a girl—or so Inge claimed. But according to Josef Söhngen (his bookseller friend from childhood) Scholl’s tears were actually for him. Scholl’s mother gave Söhngen the message: “If I should survive these times, I would want to be as ready as he was, to help students—even at risk of my own life.” Scholl didn’t know yet how long he had left. His sentence was carried out that same day.

Hans Scholl’s Legacy

If you visit the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich, you will find a square named after the Scholls (Geschwister-Scholl-Platz) and a beautiful bronze bust of Sophie in the atrium. Most books on the White Rose, including the ones written by Inge, focus on Sophie as a kind of heroine. In the critically acclaimed 2005 film Sophie Scholl: The Final Days, Hans is but a minor character.

Why the focus on Sophie, who was not very involved in the White Rose operation until fairly late? It may have started with the Gestapo’s own focus on Sophie. They spent more time interrogating her than her brother, perhaps sensing his unwillingness to give them information. During those conversations, Sophie exaggerated her role in the production of the leaflets, in an effort to spare other students’ lives.

There were family motives, too. I have already mentioned Inge’s duty to keep certain things in Scholl’s past a secret. She redacted many of his letters and diaries. She seems to have decided her brother was too complex, too challenging to be a hero, so she turned her attention to Sophie. But today, the 1937 arrest that Inge felt honor-bound to keep from the world is something that the world needs to know about.

Given that he had sexual relationships with both men and women during his short life, can we consider Hans Scholl a bisexual? Or was Rolf Futterknecht an anomaly, a case of teenage experimentation? I think that’s unlikely, considering the strong bonds he formed with a number of other men. Had the extreme social pressure to be heterosexual been lifted, my guess is that he would have lived as an out gay man. In any case, it was his imprisonment for homosexuality that radicalized and shaped him into the person he became—a symbol of freedom, resistance, and human dignity.

* Many thanks to Dr. Zoske for sharing his notes from this conversation.

AnnMarie Kolakowski is an author and a children’s librarian. She is currently working on a graphic novel about Hans and Sophie Scholl.

Discussion1 Comment

I found this article fascinating. I haven’t seen the film about the White Rose resistance, although I am familiar with the subject matter. Thank you for writing this and sharing the story of these brave young men and women. Their story has meaning for us today in these troubled times, and hopefully inspires new generations now and to come.