AS A GENRE known for pushing the boundaries of good taste, horror films occupy a unique position within American cinema. Because horror triggers an emotional response in audiences through the presentation of scenes meant to revile and offend, what is deemed to be horrific varies according to the prevailing moral standards when a film is made. In the 1930s, horror films were in a state of evolution. Trading in the supernatural, dreamlike qualities that defined 1920s horror, the films of the 1930s relied upon “otherness” as a marker of monstrosity. Villains came from far-off lands and posed a threat to everyday people. Complicating these narratives was a backlash by critics who charged that the depiction of perversion and violence in films was threatening the moral integrity of society. The end result of this effort to “clean up” films was a move by those making horror films to code stories so as to not arouse criticism.

As a reaction to sex and violence in films, a voluntary standard of ethics known as the Hays Code was a created by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America in 1930. The Code was guided by the principle that “no picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.” Although it was officially in effect from 1930 until 1968, the motion picture community did not immediately adopt the Code. In fact, the first four years after its creation saw an increase in the production of titillating films designed to shock the moral conventions of the time. Films such as Safe in Hell (1931), Employees’ Entrance (1933), and Scarface (1932) depicted prostitution, white slavery, and incest, respectively.

Horror, in particular, pushed the boundaries of good taste by creating storylines extreme enough to interest a cash-strapped audience as the Great Depression got underway. For instance, Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) contained scenes of inter-species miscegenation, while Frankenstein (1931) toyed with blasphemy when the scientist Henry Frankenstein proclaims, “Now I know what it feels like to be God!” These instances caught the attention of moral watchdog groups, chief among them the National Legion of Decency (LOD), which was affiliated with the United States Roman Catholic Church.

In 1934, the LOD entered the fray when it called for the establishment of a film rating system. By threatening boycotts en masse if filmmakers didn’t eliminate depictions of human activities deemed immoral, the LOD was able to convince the Hollywood establishment to enforce the Hays Code. Thus was established, in late 1934, the Production Code Administration, led by Roman Catholic Joseph Breen, which mandated that its board must approve all films prior to their release. It also amended the original Hays Code to include stringent guidelines as to what constituted moral and immoral behavior. Chief among the list of banned behaviors was “any inference of sex perversion,” which referred primarily to depictions of homosexuality.

As time went on, filmmakers attempted to challenge the Code’s restrictions on virtually every front. Interestingly enough, the one area in which motion pictures consistently upheld its authority was in their portrayal of homosexuality. Prior to 1934, gay men were usually depicted as sissies, as in The Broadway Melody (1929), while lesbians were shown as masculine to the point of caricature, as in Call Her Savage (1932). But even these depictions, marginalizing as they were, were all but eliminated from film in the wake of renewed enforcement of the Hays Code after the mid-1930s. This official blackout forced filmmakers to find creative new ways to express gay or lesbian themes while seeming to adhere to the Code. Homosexuality itself had to be “coded” in such a way that any depiction could be read on the surface as a heterosexual narrative. Just enough homosexual signifiers were included in the subtext to allow audiences open to a gay reading to be rewarded with a wink of understanding, while those looking for a heterosexual reading were blissfully ignorant.

Horror, especially, capitalized on these possibilities. Due to their inherently transgressive nature, monsters provided the perfect vehicles for queer coding in the 1930s, notably in Universal’s horror productions. Films such as Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), and The Old Dark House (1932) imbued their monsters with a campy æsthetic meant to tip off certain viewers while slipping past straight audiences and the LOD, which would write off the non-normative situations as mere comedy. For example, the relationship between the title character in Dracula (1931) and his manservant Renfield contains a homoerotic subtext designed to make Dracula even more menacing in the minds of the audience. His enslavement of Renfield has a sadomasochistic quality but skirts the LOD’s injunction against displays of perversion due largely to Renfield’s depiction as an effeminate, sarcastic foil. Viewers are not supposed to take him seriously, so the subtext is dismissed. These cinematic moments also served to place members of the LOD board in a difficult position. Because the sexuality being projected was not overt, admitting that you were picking up a homosexual vibe in such a movie could arouse suspicion among your colleagues.

While gay monsters were used for comic relief, lesbian monsters were crafted to evoke pity. Films used a lesbian subtext to heighten the suspense of their narratives by casting these characters as victims of their own perversions. Unlike gay men, whose threat to society was tempered by humor, lesbians exhibited all the markings of the fairer but weaker sex, who were unable to exercise free will. Their inability to internalize cultural norms resulted in emotional and physical suffering. This gender difference is attributable to the religious character of the LOD. Given that women were considered culturally to be the weaker sex, it stands to reason that this attitude would be reflected in film. Rather than making a woman an active participant in her lesbianism, and thus inciting the ire of the LOD, coding enabled the woman to be victimized by a nameless disease that, to a queer audience, would easily be read as homosexuality.

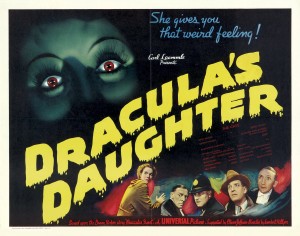

DRACULA’S DAUGHTER (1936) traces the struggle of Hungarian Countess Marya Zaleska who, upon learning of the death of her father Count Dracula, believes the curse of her being a vampire will be lifted. When her hope is not fulfilled, she enlists the assistance of psychiatrist Dr. Jeffrey Garth, who she believes has the power to cure her. When this too proves ineffectual, Marya flees to Transylvania intent on turning Garth into a vampire and her everlasting companion.

DRACULA’S DAUGHTER (1936) traces the struggle of Hungarian Countess Marya Zaleska who, upon learning of the death of her father Count Dracula, believes the curse of her being a vampire will be lifted. When her hope is not fulfilled, she enlists the assistance of psychiatrist Dr. Jeffrey Garth, who she believes has the power to cure her. When this too proves ineffectual, Marya flees to Transylvania intent on turning Garth into a vampire and her everlasting companion.

Film historians have found a number of scenes in which a lesbian subtext is evident in Dracula’s Daughter. The most obvious is a scene between Marya and her manservant Sandor. Upon returning home after disposing of Count Dracula’s body, Marya confides to Sandor that her curse will be lifted and that she’ll finally be able to “live a normal life now, think normal things.” An audience in the 1930s would easily equate normalcy to heterosexuality, and the scene plays upon Marya’s desperation to be cured of her inner conflicts.

Another scene of note occurs when Dr. Garth accuses Marya of “concealing the truth” about herself, to which Marya responds that the truth is “too ghastly.” While the audience knows the truth to be that she’s a vampire, they also understand that Sandor procures female models for her whom she has undressed before killing them. This suggestion of a female gaze upon female nakedness implied a subtle perversion, never explicitly named, that would not have been lost on some viewers at the time.

What’s more, it isn’t only the dialogue that supports a queer reading of Dracula’s Daughter. The camera is used to great advantage in portraying the longing Marya feels toward her female victims. Unlike her treatment of her lone male victim, who’s dispatched with little fanfare, Marya slowly seduces her female victims with her gaze. The camera lingers on Marya as she looks upon Lili’s exposed body or when she appears more interested in kissing Janet than in killing her in the film’s penultimate scene.

What these coded instances point to is the creation of a new kind of monster in which lesbian undertones are used to increase the revulsion experienced by the audience. In his pathbreaking work The Philosophy of Horror, Noel Carroll sets up the criteria for what constitutes a monster. First, it must be a being that exists outside of conventional scientific understanding. Second, the monster must be viewed by the audience as both threatening and impure. Adding to the work of social anthropoligist Mary Douglas and her association of the impure with the monstrous, Carroll contends that “an object or being is impure if it is categorically interstitial, categorically contradictory, incomplete, or formless.” An example of a contradictory being would be a human who is also a vampire.

With these caveats in mind, Marya is clearly the monster of the film. Not only is she a vampire with a long list of victims in her wake, she is also aware of her “cravings.” What she desires is by her own definition unnatural, so these cravings mean that Marya partakes of the forbidden. The audience sees her continually attempting to resist her urges, but she’s unsuccessful because the vampire part of her overrides the human part. Interestingly, while she does engage in physical contact with her victims when she drains their blood, Marya uses hypnosis to subdue them rather than physical restraint. Her main physical interaction with her victims comes after they’ve been rendered comatose. Indeed, Marya is aroused by looking at her female victims rather than by touching them.

Marya struggles with a desire to kill over which she has little control. As Carroll observes, it is not enough to simply be threatening. A monster must also be impure. And in the 1930s and 1940s there was no easier way to imply impurity than to suggest lesbianism. Audiences in those decades were conditioned to view homosexuality as a violation of the natural order. The coding evident in this film genre was intended to suggest that such women were possessed by innate desires over which they had no control, a force to be feared and resisted.

Marya’s status as a monster is underscored by the threat she poses to traditional domesticity. In Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film, Harry Benshoff contends that coded homosexuality “looks ahead to a new set of signifiers which become the chief foci of the monster movie’s narrative—an increasing domestication of the monstrous figures.” Marya is involved in a relationship with her servant, Sandor, in which aspects of the traditional husband-wife dynamic are both pedestrian and perverse. Not only does Sandor protect her from outside discovery, but he also exhibits the role of provider by literally procuring the bodies that she will consume. Adding to their unique dynamic is Sandor’s own questionable heterosexuality. Benshoff refers to Sandor as “an overly coiffed, surly queen,” and his subsequent relationship with Marya harks back to the “beard” relationship that homosexuals sometimes enacted in order to avoid detection. It is telling that Marya wears the ring she uses to hypnotize her prey on her left ring finger, the finger upon which a wedding band is traditionally worn. It demonstrates a commitment to her life with Sandor, so when she begins to express an interest in Dr. Garth, she is essentially committing a form of adultery. As a result, the audience not only reads Marya as betraying Sandor but also as a dangerous threat to the “normal” relationship between Dr. Garth and Janet.

Complicating the superficial domestication of Marya is that she has been medically determined to be abnormal. While monsters would often fight against their abnormality, as in Bride of Frankenstein (1935), their battle almost always resulted in defeat. Horror films of this period used doctors—specifically psychiatrists—to paint monsters as threatening. Given that homosexuality was deemed a mental illness in this period, it’s not surprising that most horror narratives showed the psychiatrist attempting to cure the monster. The intersection between psychiatry, the monster, and homosexuality is best expressed by Benshoff: “Homosexual signifiers help to characterize a terrible secret or a group of odd fellows, a trope that both draws on and foregrounds the phenomenon of the closet, wherein monster queers who are not ‘out’ may choose to ‘hide.’” As a woman who hides in the form of a marriage, Marya’s monstrous nature is triangulated between her unnatural cravings, her desire to be rid of her curse, and the psychiatrist she entrusts to cure her.

Marya’s faith in Dr. Garth comes after she has exhausted all other options. At a dinner party one evening, she meets the doctor and takes heed of his assertion that “any disease of the mind can be cured.” In a vulnerable state after the death of her father, which she believed would lift the curse, Marya has come to the dinner party after having recently killed a victim. When the other party guests support Dr. Garth’s claims with stories of their own, they function much as a Greek chorus did. By their validating the doctor’s claims, his legitimacy in the mind of Marya is increased. When Marya meets privately with the doctor to convince him of her sincerity to be cured, he equates her “horrible impulses” with those of an alcoholic locked in a room with liquor. To lift the curse, the doctor contends, Marya must have the will to fight it.

The belief that lesbianism is an impulse subject to control permeated American culture in the 1930s. This was the period in which conversion therapy, ameliorative strategies designed to change a person’s sexual orientation, first gained national prominence. In this respect, Marya is ultimately seen as giving in to an impulse that is in fact controllable: she has embraced her life as a vampire. Thus her death is no longer a tragic destiny but instead the expected consequence of choosing a life of perversion.

References

Benshoff, Harry M. Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. Manchester University Press, 1997.

Carroll, Noël. “The Nature of Horror,” in The Philosophy of Horror; Or, Paradoxes of the Heart. Routledge, 1990.

Elizabeth Erwin is a feature writer for the on-line magazine horrorhomeroom.com. This piece was adapted and expanded from two items that ran in that venue in June 2015.