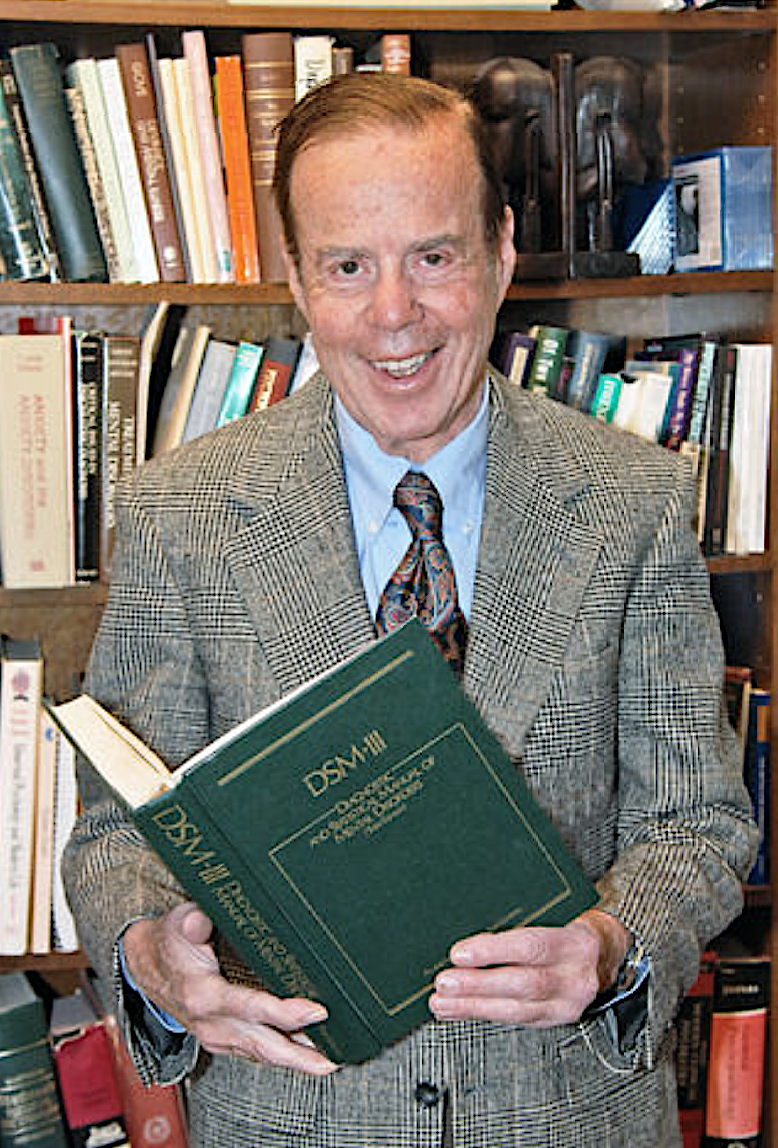

AS PART OF OUR RECOGNITION of the fiftieth anniversary of the declassification of homosexuality as a mental illness in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), we interviewed one of the foremost authorities on this event and on LGBT psychiatric issues and APA history in general. Jack Drescher, MD, is clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University and a faculty member at Columbia’s Division of Gender, Sexuality, and Health. He is a past president of GAP—the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry—and remains very active in this organization.

Dr. Drescher is the author of Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man (2001) and (with Joseph P. Merlino) editor of American Psychiatry and Homosexuality: An Oral History (2012), among many other books and papers. He is emeritus editor of the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health. He’s an expert media spokesperson on issues related to gender and sexuality who has appeared on major news networks and in mainstream publications.

This interview was conducted via Zoom in late August.

Gay & Lesbian Review: This being the 50th anniversary of the delisting of homosexuality as a mental illness in the DSM, we’re devoting the next issue of the magazine to that event, which is why we’re very excited to have the opportunity to interview you. Actually, there’s a slight ambiguity regarding the anniversary year. The famous “John Fryer” panel was in late 1972, the APA board of directors voted to delist late in 1973, and the whole membership voted to do so in 1974. What year or event is recognized as the official turning point?

Jack Drescher: It’s 1973, when the board voted. Some members were not happy about that vote, so they challenged the board’s decision by using a bylaw, which doesn’t exist anymore, that allowed 200 people to sign a petition to question an administrative decision by the board. The question that was put to the membership was something along the lines: “Do you support the Board of Trustees’ decision to remove homosexuality, and the process that they used to come to that decision?” So, they weren’t really asking the psychiatrists whether they thought homosexuality was an illness, because most of them at the time probably did. They were asking a more narrow question: “Do you support the process that led the board to make its decision?”

G&LR: And was it an overwhelming vote in favor of supporting the board?

JD: The APA had about 20,000 members at the time. Around 10,000 members voted, and 58 percent voted to support the board decision.

G&LR: In the next issue, I have what started as a letter to the editor from Lawrence Hartmann, who was responding to an article about the 1972 panel that we had run, which really stressed the protests as critical to the decision. Dr. Hartmann wrote in to remind us that the decision was made by the APA after much hard work and discussion. [See Hartmann’s “Open Letter” in this issue.] So, there’s a bit of a debate between the role of the demonstrations versus the inner workings of the APA itself. What factor was decisive in your view?

JD: That’s a good question. I’ll qualify my response by saying that Larry Hartmann was there, and I was not. In the early ’70s, I was still in college. My first exposure to the story came from a very important book, which I recommend to everybody, Ronald Bayer’s Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis. Bayer is an ethicist at the Hastings Institute. He interviewed all the players who were involved in those years, and he put together a wonderful story of how the decision-making took place.

I read the book when it came out in 1981, when I was an intern or a second-year resident. It became a template for my thinking going forward, about what the issues were that needed to be addressed. Even though homosexuality was removed from the DSM in 1973, I had a rude awakening when I applied for an internship in 1980. I graduated from the University of Michigan in that year, and I wanted to come back to New York City, where I’m from, and live and work in Manhattan. Many of the programs were run by psychoanalysts who had disagreed with the 1973 decision. I came back to find that in New York, this liberal, cosmopolitan city, psychiatry and psychoanalysis were quite conservative.

G&LR: You’ve been involved with the DSM in various capacities over the years. We’re now up to DSM-5-TR [DSM-5-Text Revision], which is not surprising, given that psychiatry is always evolving. But it seems that this change, perhaps more than any other, had an impact that rippled outside the APA and into the larger society. Would you agree?

JD: Soon after the Stonewall riots, the Gay Activists Alliance decided that they were tired of polite protests about homosexuality. In the 1960s, the idea was that gay people would dress up in conservative clothing and carry very well-crafted signs saying “Please stop discriminating against us.” But following Stonewall, the homophile movement became more politicized. We had the Civil Rights movement, antiwar protests, the women’s movement, so the gay rights movement decided to get a little bit more aggressive. They came to the APA meeting in San Francisco and disrupted the meeting entirely, which did of course get APA’s attention. So that was really the beginning, in 1970, in San Francisco. And then the following year—it was in Hawaii—they had activists like Frank Kameny and Ron Gold and a few others on a panel called “Lifestyles of Non-patient Homosexuals.” It was the first time APA had non-patient gay people talking to psychiatrists about the harm done by the diagnostic manual, the ways in which people’s everyday lives were affected by a psychiatric diagnosis, which I don’t think many psychiatrists had actually thought about.

The ’71 panel was very successful, so they decided to invite the activists back. I think it was Kay Lahusen, Barbara Gittings’ partner, who said: “Well, wouldn’t it be great if you found a gay psychiatrist to be on the panel?” But where to find an openly gay psychiatrist in 1972, when homosexuality was still illegal in most states? You could lose your license, your job, referrals. They found Dr. John E. Fryer, who was willing to appear in disguise as “Dr. H. Anonymous.” On the panel, he wore a Nixon Halloween mask, a fright wig, and an oversized tuxedo, and he used a voice-disguising microphone. I like to show a picture of Dr. Anonymous on my slides and say: “This is what an openly gay psychiatrist looks like in 1972.” And I think that did have an impact. The pure theater of the event had an impact on the audience, because a lot of people didn’t know they had a gay colleague, or two, or three, at all.

I’d like to say that trans rights in the U.S. right now are where gay rights were in the 1970s, which is that most people didn’t know that they knew a gay person. Most people today don’t know that they know or have met a trans person. In the ’70s most people were firmly against gay marriage. It’s only after the long conversation that we’ve had about homosexuality over the last fifty years that a majority of Americans now accept gay marriage. So the trans community may have to wait fifty years too, unfortunately, for attitudes to change.

G&LR: So it sounds as if there was a time lag from the 1973 vote to acceptance within the psychiatric community. I’m sure the vast majority of psychiatrists today are fine with homosexuality and don’t regard it as a mental illness. So how did this change come about?

JD: That’s a good question. I see two parallel processes, not happening at the same time. One is the general process within the culture. We didn’t really have a national debate about gay rights until 1993, when President Clinton tried to overturn the ban on gays in the military. Prior to that, discussions of homosexuality were usually relegated to whispers and backrooms. But now conversations began to be had aloud, and once that happened, it desensitized people to the subject. It became possible to engage people in an open dialogue.

So, in 1973 homosexuality was removed from the DSM, but it was only in 1989 that the Immigration and Naturalization Service finally removed homosexuality as a reason why you couldn’t immigrate to the U.S. Even though the diagnosis had been removed in mid-’73, it continued to be listed as a mental disorder by the U.S. government.

By the way, at this time there was psychiatry and then there was psychoanalysis. The latter was deeply opposed to this change in the ’70s. Psychoanalysis was just at the beginning of its decline in importance, having ruled American psychiatry in the middle of the 20th century. You started to have a pharmacological revolution starting in the ‘50s, with medications being available that were working to treat patients: antidepressants, antipsychotic medications, etc. The American Psychoanalytic Association (APsA) was threatened with a lawsuit by the late gay psychoanalyst Richard Isay and the ACLU for their discriminatory policies. So they changed their policies in ‘91 and ‘92, and then they started to become a little more forward-looking. In fact, APsA was the first mental health organization in the country to support same-sex marriage, in 1997.

But before that, psychoanalysis was very rigid, very hidebound. They had their theories, and you could not argue with their theories. In psychoanalytic training institutes, if you argued with the teachers, it was because there was something wrong with your personality, something to work out in your own analysis.

G&LR: After the events of 1972 and ’73, homosexuality was effectively delisted from the DSM, and it seems that gender then rose to the fore. I think it was in 1980 that APA listed “gender identity disorder” as an official diagnosis. It almost seems that this was kind of a sop to conservatives who were still disgruntled about the ’73 change.

In creating the DSM-III, Spitzer wanted to solve the problem that, depending on where you lived and practiced, patients might get very different diagnoses. We know, for example, that if you come from a community of color and you have psychotic symptoms, you’re more likely to get a schizophrenia diagnosis, which has more stigma and perhaps a worse outcome than, say, a mood disorder with psychotic features. So Spitzer wanted to create standards of diagnosis such that every diagnosis would have criteria, and you couldn’t make a diagnosis unless you were trained on how to use these criteria and fit them to the clinical situation you were observing.

G&LR: The “gender disorder” diagnosis remained in place for quite a few years. You were deeply involved in producing DSM-5, which ultimately threw out that diagnosis and replaced it with “gender dysphoria.” What was going on during those intervening years that led to this shift?

JD: There was lots of media attention and interest among the general public about the DSM-5 development process—not just the gender diagnosis, but other diagnoses as well. Some advocates within the transgender community began calling on APA to remove the diagnosis of what was then called “gender identity disorder of adolescence and adulthood” from the DSM the way homosexuality had been removed in 1973. I became very interested in the question of the parallels and contrasts between the two diagnoses and wrote a paper in 2010 called “The Queer Diagnoses.” One parallel is that both psychiatric diagnoses are highly stigmatizing. One of the differences is that people who have what we now call gender dysphoria require a diagnosis in order to access the treatment they need, so the problem that I saw was that removal of the gender diagnosis to reduce stigma created a problem of maintaining access to care.

G&LR: Whereas people who were once diagnosed as homosexuals just wanted to be left alone: Keep us out of the psychiatric rule book, thank you.

JD: Well, gay people can have depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and other kinds of psychiatric problems.

G&LR: But those are problems that anyone can have, no?

JD: They’re problems that everybody has, but there’s no need for a psychiatric diagnosis called homosexuality, except if you want to treat the homosexuality, and there’s very little evidence to support the idea that treating homosexuality leads to any good outcomes.

G&LR: Still, you wrote a book titled Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man, whose title implies that gay men are distinctive in some way that calls for a separate approach. Is this a fair assessment?

JD: I tried in my book to provide a cultural context, to think about gay identity within the cultural context of a heterosexist, homophobic society. I grew up in a Jewish, observant household—not super religious, but religious enough—in Brooklyn, in Bensonhurst, which was then a mixed Jewish-Italian neighborhood. When my Italian neighbors and friends heard from their priest in their catechism classes in preparation for their first communion that Jews killed Christ, they would ask me: “Why did the Jews kill Christ?” I didn’t know, so I asked my mom, and she said: “You go back and tell them that the Romans killed Christ.” From that cultural context, parents teach their children how to deal with the prejudices of the wider culture. What’s unique about being lgbtq is that kids are born into the enemy camp. Often the parents share the prejudices of the wider world and lack the ability to teach their children how to deal with those prejudices.

I saw a family of a child who had come out as a different gender than the one assigned at birth. The parents were terrified, because they didn’t know what harm their child would face in the world. That was helpful for their child to hear, because they [the child]have the unfortunate task of trying to educate the parents about the dangers that they actually face as they learn to negotiate the wider world.

G&LR: As you mentioned, gender is currently a major issue that we’re trying to resolve as a society. There’s a lot of terrible legislative activity going on, of course. There’s a lot of discussion about age: at what age do you recognize someone as having gender dysphoria? There’s now discussion about the use of hormones to delay puberty while decisions are being made. Do you have a viewpoint on this issue?

JD: So, here’s the interesting thing that I’m discovering. When the DSM-5 was being put together in the beginning, among the various attacks on APA and the manual were attacks on the work of Ken Zucker, who chaired our Workgroup on Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders, because his clinic in Toronto was seen as practicing something that activists called conversion therapy for trans kids. So I became interested in this subject. I don’t treat children myself, or adolescents before eighteen or nineteen. With my colleague William Byne, we did a special issue of the Journal of Homosexuality in which we invited seven clinics to submit papers telling us what they did. Five of them sent in papers.

So here are some interesting facts. Puberty suppression hormones were approved by the FDA for safe use in 1980. In 1981, they were first used to treat a condition called precocious puberty, an example being a child who starts entering puberty at the age of nine, because there was a belief that if puberty occurred too early, there could be adverse psychological and physical effects. And today, pediatricians are still doing puberty suppression with puberty blockers, and in articles about precocious puberty, they’re calling puberty-blocking the gold standard.

In the 1990s, a clinic in Amsterdam noted that children who have what we today would call gender dysphoria were not necessarily growing up to be transgender after puberty. There are about eleven studies since 1970 of kids who went to these specialized gender clinics around the world, and the majority of them, anywhere from fifty to eighty percent, did not grow up to be transgender. They grew up to be gay and cisgender, and a few even grew up to be heterosexual and cisgender.

The doctors observed that in some cases gender dysphoria doesn’t go away until after puberty. So, if I’m treating a particular child, I don’t know if they’re going to grow up to be transgender or gay or cisgender. I don’t know, but they’re approaching puberty, and they’re having panic attacks, because they still are dysphoric, and they don’t want to go through puberty, which will change their secondary sex characteristics in a way that will make it more difficult to transition later on.

In the 1990s, they began offering puberty suppression in the Dutch clinic. Their idea was that if the child—who is, say, fourteen years old and they’ve been on puberty blockers—changed their mind, they could stop the puberty blockers and they would simply have a late onset puberty. But if they continued to be dysphoric, then they would have an easier transition later on in life, when they were old enough to get all the treatments that are available to transition.

So that’s what has been going on for more than twenty years. You would hardly call that experimental. The debates in the old days, ten years ago, when I got into this subject, were not about whether to give kids puberty blockers but what to do with the child before that happened—whether you should try to change their mind, help them to transition them socially, or just let them evolve naturally. Well, the debate has shifted in an extraordinary way, to include people who think that nobody should get treatment at all. That’s what you’re seeing in these laws that are being passed in red states. They want to make offering treatment a crime. The people who are passing these laws believe that no child should have any treatment—other than talking about their feelings—before they’re eighteen at least.

G&LR: My guess is that you would advocate a case-by-case approach, correct?

JD: Yes, of course. There are two kinds of children. There are children who will benefit from treatment and children who might not, and the goal for anybody treating these kids is to know as much as they can on an individualized basis, what to do for this particular child. But when you pass laws that say no one should get the treatment, what you’re saying is you’re going to privilege the care of the children who grow up to be cisgender at the expense of the kids who might grow up to be transgender. And that to me is a very serious ethical problem.

G&LR: Wrapping up: here we are fifty years after the big decision and the DSM revision, and the whole field of psychiatry is so radically different now from what it was back then. So, looking forward, is it possible to see any trends within psychiatry as a discipline or its involvement with LGBT-related concerns?

JD: Well, first of all, it’s a truism among psychiatrists that we are notoriously bad at predicting the future. So I’ll start with that. Like many disciplines, psychiatry is dealing with issues related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. The recently elected president of APA is an openly gay man, Petros Levounis, who’s a Harvard graduate. Larry Hartmann was president of APA, but not everybody knew he was gay when he was running. I ran as an openly gay man in 2005, but I didn’t win. But I wasn’t really a viable candidate. And now I’m actually on the faculty of a psychoanalytic institute that wouldn’t accept me back in the ‘80s, and I was elected a director at large of the American Psychoanalytic Association a few months ago.

G&LR: Congratulations! And thanks so much for sharing your time and wisdom.