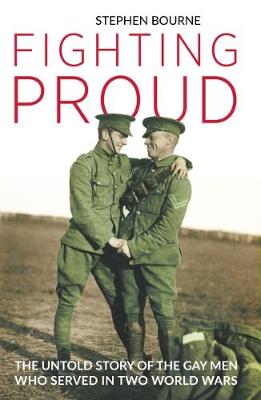

Fighting Proud: The Untold Story of the

Fighting Proud: The Untold Story of the

Gay Men Who Served in Two World Wars

by Stephen Bourne

B. Tauris. 236 pages, $27.50

OVER A QUARTER CENTURY ago, Allan Bérubé’s groundbreaking book Coming Out Under Fire (1990) brought attention to the plight—and the heroism—of thousands of gay and lesbian Americans in the armed services during World War II. A monumental piece of scholarship, it justly deserved the awards and accolades it received.

Now, Stephen Bourse, a British writer and historian, has set out to investigate his country’s version of this story. Not surprisingly, it’s a story fraught with the same prejudice and hostility as the American one. “I regard the act of homosexuality in any form as the most abominable bestiality that any human being can take part in,” declared Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, the so-called “Spartan General” and hero of the Battle of El Alamein. In such a climate, gay British soldiers lived a “knife-edge existence,” Bourne says, “fearful of being found out and court-martialed”—a sadly familiar tale.

In Fighting Proud, Bourne describes his book as “exploring and highlighting the many stories about gay men’s lives in the two world wars which have never been grouped together and published in one volume.” These stories—“fragments I had come across through the years”—include ones about gay servicemen not only on the front lines but on the home front as well. Alas, “fragments” is the operative word here, for the book amounts to little more than a tantalizing pastiche of bits and pieces of gay history.

Bourne opts for anecdotal and eye-witness accounts, which, he says, “can bring out into the open details that are sometimes missed by academics who are immersed in theoretical concepts and approaches.” Fair enough, but, surprisingly, almost all of the scraps he culls come from previously published sources. Consequently, the book’s subtitle, “The Untold Story of the Gay Men Who Served in Two World Wars,” seems disingenuous, as almost all of Bourne’s stories have already been told.

Information about homosexual servicemen in World War I is difficult to come by. To his credit, Bourne addresses a number of interesting topics related to that war: the alleged homosexuality of Lord Kitchner, the most celebrated British military leader of Word War I; the “comradely and platonic” friendships between younger and older soldiers; the unfortunate destruction of letters, photographs, and diaries “for fear of blackmail or legal recrimination.” In one chapter, he gives capsule biographies of a number of legendary gay figures of Word War I—among them poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, Lawrence of Arabia, diplomat and Irish Nationalist Roger Casement, and the actor and composer Ivor Novello. Disappointingly, however, these profiles run to less than a page each, mere thumbnail sketches of scant interest or worth.

The majority of Fighting Proud focuses on Word War II, where information is more readily available. Bourne notes the surprising number of gay men in the armed services during that war who, though relatively open about their sexuality, were able to “avoid trouble.” How did they do it?

Despite extreme attitudes like those expressed by Lord Montgomery, Bourne (quoting a friend) claims that “there was a tolerance exercised in all but the most extreme situations.” This “relaxed attitude” can be attributed, in part, to the dire need the British government had for all available manpower. The Armed Forces, some gay men later claimed, “weren’t fussy about who they accepted.” Visibly gay men were even commandeered to service as drag performers for the troops. The brass refused to remove these homosexual entertainers because, as one sailor said, “they were too valuable to be discharged. In wartime they were good for morale.”

Gay servicemen also survived through sheer pluck, humor, outrageousness, and give-as-good-as-you-get crudity: “What goes up my arse won’t give you a ’eadache,” Terri Gardener, an officers’ cook, used to tell those who accused him of being a “brown hatter.” Nevertheless, as Bourne points out, even though same-sex relationships were often tolerated, they were “rarely, if ever, openly discussed.”

Along the journey through the book’s 23 short chapters, we learn some interesting facts: that working-class communities were more tolerant of gay men than were middle-class ones; that gay men developed a slang, Polari, with which to privately communicate among themselves; that on the home front there was a lot of sex during blackouts; and that in the Navy, sailors proved to be “a fairly randy lot and masturbation was not at all uncommon.”

Bourne, who has written extensively about LGBT British history, has certainly done his homework. His bibliography is impressive. But, for my money, he is too fond of citing long passages from other books and too hesitant to indulge in commentary and deep analysis. Indeed, block quotations comprise close to a third of the book. In the end, the greatest asset of Fighting Proud is that it will send many readers to the library in search of the numerous other biographies, histories, and personal accounts from which Bourne so lavishly quotes.

Philip Gambone has just completed his sixth book, a memoir titled As Far As I Can Tell: Finding My Father in World War II.