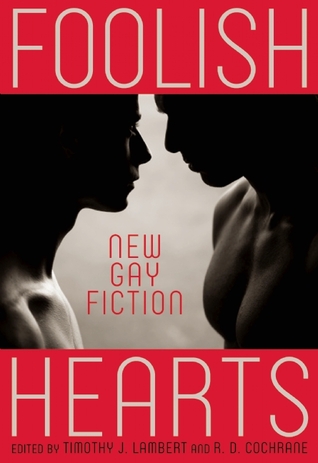

Foolish Hearts: New Gay Fiction

Foolish Hearts: New Gay Fiction

Edited by Timothy J. Lambert and R. D. Cochrane

Cleis Press. 232 pages, $15.95

THE STORIES in Foolish Hearts remind us that the short story was once a mainstream art form for ordinary folks to read and enjoy. Most of these stories are gay romances that end either happily or poignantly and, for the most part, don’t spend much time in the bedroom. Husbands are tempted but choose to be faithful; boyfriends realize that the great love they have always searched for is sleeping right next to them. Change the gender of a character or two, and these stories could have appeared in mid-20th-century women’s magazines, sandwiched between handbag pictorials and gossip. This is not meant as a criticism. Many stories now acknowledged to be masterpieces were first published in Vogue, Mademoiselle, and Harper’s Bazaar by writers like Truman Capote, Shirley Jackson, and Dorothy Parker. Still, most of stories in these magazines were competent romances, not meant as more than light entertainment.

Thus it would be wrong to criticize the stories in Foolish Hearts for a lack of depth, as most have few literary pretensions beyond entertainment. There is not only pleasure but also a sense of liberation in these heartfelt gay romances that are only lightly touched, if at all, by homophobia and its discontents. Several of the stronger stories revolve around gay marriage and offer clever and sometimes emotionally affecting variations on traditional romantic motifs. In Erik Orrantia’s “Victoria,” two closeted vaqueros who run a ranch in Jalisco fight about whether to get married in Mexico City. In Tony Calvert’s “Hello Aloha,” the best man at a gay wedding at Disneyland is jarred out of his depression by the costumed character Goofy. Although what looks at first like a story about a furry fetish resolves itself conventionally, Calvert uses the odd specifics of a Disney wedding to freshen the romance.

Some of the stories are undermined by excessive elements of fantasy. ’Nathan (the apostrophe is correct) Burgoine’s “Struck” offers a credible, enjoyable romance between a beaten-down bookstore employee and a color-blind security guard, but it suffers from the distracting gimmick of an apparition who periodically informs the protagonist of the next plot turn. And talk about a gimmick: in another story it is revealed that the protagonist’s object of desire is a literal handsome prince! Craig Cotter’s “Rochester Summers” offers a fragmented narrative of two teenage boys who seem to be in love, but they don’t discuss or physically express their affection except through hugs and the wearing of each other’s dirty clothes. This story lacks resolution. While life itself frequently peters out unsatisfactorily, such peterings in fiction need to seem intentional, and this one does not.

Three stories stand out. Paul Lisicky’s “Nude Beach” is a complex portrait of a man who meets and loses his ideal partner at the beach. As his loss becomes more apparent, the hero strives to delude himself. The detached point of view allows for a greater distance from the romanticism that drenches the anthology as a whole. By contrast, Felice Picano’s “New Kid in Town: 1977” is flip, fluent, and wry. The story is distinguished by the specific detail and fast pace of an Angeleno “stupendous, star-studded orgy”—officially, a publicity event for a disco diva—where the narrator scores a date to take in some Stravinsky with an advance man at the record company.

Andrew Holleran’s “Symposium,” which concludes the volume, is both the strangest and most accomplished story. Holleran fulfills the promise of his title and delivers a literal symposium along Hellenic lines: a drinking party between men that touches on poetry, philosophy, and love. The primary drinkers here are two middle-aged writers who relax at a gay resort after a panel discussion of the question, “Is there a gay sensibility?” They’re joined by a 25-year-old blogger who wears his master’s collar, an unpublished novelist, a British scholar of the German homophile movement, and a prematurely graying publisher who misses New York. This story easily could have been pretentious, but I cannot imagine a more successful delivery of this metafictional conceit.

________________________________________________________________

Jeff Solomon is a lecturer in English at the Univ. of Southern California.