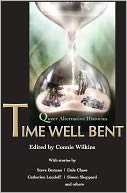

Time Well Bent: Queer Alternative Histories

Time Well Bent: Queer Alternative Histories

Edited by Connie Wilkins

Lethe Press. 184 pages, $15.

THE CHIEF PLEASURE of this varied anthology lies in its imaginative breadth. Editor Connie Wilkins has collected fourteen stories from established and emerging writers of GLBT fiction that speak to both the “queer” and the “histories” of the subtitle. The editor’s introduction positions the collection as a corrective to the Western tradition that has “either ignored, glossed over, or vilified” the presence and experiences of glbtq people. That this anthology offers an alternative through fiction rather than scholarship adds a twist to the volume’s queerness. These are queer stories about queered history.

The alternative history genre frees the contributors to play with notions of queerness in a variety of ways. Some of the stories ask how our contemporary understanding of history might be different through a queer lens, if that lens were applied at crucial turning points in the past rather than as a political or cultural claim (or reclamation). For example, Emily Salter’s “A Happier Year” envisions the sexual and romantic lives of her World War I–era homosexual characters had E. M. Forster published Maurice when it was written (1913–14) rather than in 1970. Sometimes, as in C. A. Gardner’s “At Reading Station, Changing Trains” and Lisabet Sarai’s “Opening Night,” the change comes too late for the characters who wrought them, in these cases T. E. Lawrence and William Gilbert respectively.

Other stories drape a queer mantle on historical figures and imagine (or encourage the reader to imagine) how that alternate identity might have affected historical events. “Morisca,” by Erin MacKay, poses such a question about the 15th-century court of Spain’s Isabella, while Dale Chase leads us to a very different Bill of Rights by way of Thomas Jefferson and his secretary–lover. The same is true for M. P. Ericson’s “A Spear against the Sky,” which places the two Celtic warrior queens Cartimandua and Boudicca in a lesbian-inflected 1st-century alliance against the Romans. And Catherine Lundoff’s “Great Reckonings, Little Rooms” makes great sport of a gender-bent Shakespeare sibling and a surviving Kit Marlowe.

Where stories in Time Well Bent layer queerness onto colonialism, the effect is a dreamlike array of possibilities. Rita Oakes’ story “A Wind Sharp as Obsidian” allies a Mayan goddess with Meso-America’s “first mestiza” Malinalli against the invading Spaniards. And in “The Final Voyage of the Hesperus,” Steve Adamson uses dream sequences to show how history treated Indian migrants to the West Indies in counterpoint to the “reality” of a migration free from colonial depredations and slavery. The European protagonist in Sandra Barret’s “Roanoke” benefits from her exposure to a Native third-gender tradition, so much so that the colony might actually survive. Queer indeed.

The most intriguing tales in this collection are those that simply tell a story of a gay person making modestly queer choices in the world as it was. As Barry Lowe asserts in the author’s note to “Sod ’Em,” “the deeds of the little people, those not prominent on the world history stage, can have widespread ramifications.” In Lowe’s story, the ripples flow from a humble Irish scribe’s rewriting of the Old Testament story of Lot and the Angels of Sodom on the eve of the 9th-century Viking invasions of the British Isles. In Steve Ber-man’s “The High Cost of Tamarind” and Connie Wilkins’ “The Heart of the Storm,” local lore (revolutionary Mexico’s in the former and World War II Brittany’s in the latter) informs the actions of characters such that history itself isn’t altered overmuch, but our modern-day interpretation of events is thrown into question. Finally, there’s the queerest story of the bunch, Simon Sheppard’s “Barbaric Splendor,” which casts Samuel Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” as history rather than fantasy. Wonderful as it is, Sheppard’s story is not alone in its muscular imagination, solid research, deft writing, and clean editing.

The authors’ notes in themselves make a convincing argument for the power of queer alternative history. This collection stands up equally well to a dip in here or there to explore a favorite era or personage through “queer alternative” eyes, as it does to a cover-to-cover reading—each an edifying path of historical (re)discovery.

________________________________________________________

Gaelan Lee Benway, PhD is associate professor of sociology at Quinsigamond Community College in Worcester, Mass.