SALMAN RUSHDIE’S twelfth novel is titled The Golden House (Random House). Set in New York City, the story opens on the day of Barack Obama’s inauguration, when the enigmatic, foreign billionaire Nero Golden takes up residence in “the Gardens,” a storied gated community in Greenwich Village. With his three sons, Golden ceremoniously arrives to re-establish himself in the U.S.

Significantly for readers of this magazine, one of Golden’s sons struggles with his gender identity and wrestles with the existential choices it implies. The 400-page book, which has been described as part The Great Gatsby and part Bonfire of the Vanities, tells the story of the American zeitgeist over the past decade: the birther movement, the Tea Party, the superhero movie, and the insurgence of ruthlessly ambitious, media-savvy villains who wear makeup and have colored hair.

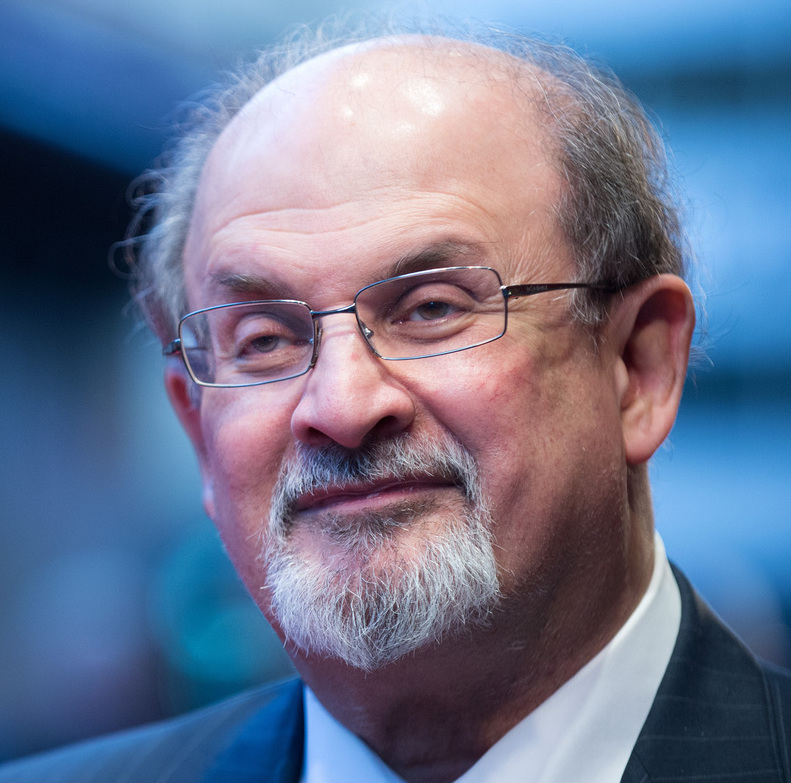

Born in India in 1947, Sir Salman Rushdie was educated at Cambridge University and came of age in England—indeed he is a knight of the realm—but has lived in New York City for much of his adult life. It was his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, that provoked a fatwa on his life, issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989. The pronouncement placed Rushdie in mortal danger for the next decade, and the book’s publication was met with demonstrations around the world. But Rushdie survived; the book went on to become an international bestseller; and many more would follow. Even before Satanic Verses, Rushdie had won the Booker Prize, in 1981, for Midnight’s Children. Subsequent books have included novels such as The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999) and The Enchantress of Florence (2008) and several collections of essays.

This exclusive interview was conducted by telephone in August.

— Frank Pizzoli

Frank Pizzoli: What did you hope to achieve with The Golden House?

Salman Rushdie: I wanted to tell a good story that people would enjoy reading. My previous novel was kind of a fairy tale deal, and I thought I would try to write an opposite novel with a large, panoramic view, a social realist novel. That was my starting point.

FP: So that was your use of realism with references to film, the arts and literature?

SR: Yes, I was trying to make a portrait of a particular moment in American life, the last eight years or so. Particularly New York City, just trying to smell what’s in the air and respond to it. That was one part. The other part is a story about this crazy family which I’ve probably had in my head for a while before they’d come to New York. I just brought the two together.

FP: Is Nero Golden a composite?

SR: He comes from the particular background of the Indian super-rich. I know some of those people. Nero is not based on anybody in particular, but he is also not a composite. I don’t think it would be right to say he is a composite. He’s pretty much himself.

FP: All great cultures have their madmen—Rome, Germany, now the U.S. Is this our post-Cold War dark age?

SR: It has certainly darkened very fast in the last six months or so. I’d actually thought the previous eight years, a lot of them, were a time of considerable optimism. And the changing of that optimism of 2008 to its antithesis in the present is what I was trying to capture [in The Golden House].

FP: Your storytelling sense of humor comes through in The Golden House and has made me laugh out loud.

SR: I’m glad to hear it. I’ve been trying to persuade people that this novel—my novels—are funny. People have somehow forgotten there is a comic dimension to my writing.

FP: Are you expecting blowback on this book? Did you intend to make the point that the U.S. and our enemies are equally absurd?

SR: I don’t know about blowback, though I’ve had blowback in my time. I don’t frankly give much thought to it. I just try to do the thing I have in front of me and hope that people respond to it in the right way.

FP: Does your sense of humor help you survive?

SR: No question. A sense of the absurd and the ridiculous is a great asset in dark times. That certainly has been true in my own dark times. On a daily basis, I’m grateful for the comedians who respond to the situation in the U.S. If it weren’t for Stephen Colbert, John Oliver, and Samantha Bee, our days would be a lot bleaker.

FP: A quote about Nero Golden: “This was a powerful man; no, more than that – a man really in love with the idea of himself as powerful.” Trump?

SR: I wasn’t only thinking of Trump. That’s a statement that could be made about many people who are corrupted by power. As the old saying goes: Absolute power corrupts absolutely.

FP: The same can be said of anyone puffed up about himself?

bOver the years I’ve met quite a few extremely powerful people, and the love of power is something I always found extremely unattractive. The most impressive powerful people I’ve met genuinely see themselves as public servants. They’re not obsessed with the idea of themselves as powerful. So, I think there’s both kinds of people. Some people respond in a very ethical way to having power. They don’t see it as a tool or as an indication of their own glory.

One of the key elements of Golden is for me to ask if it’s possible for a man to be simultaneously evil and good. That was the kind of character I was trying to build and explore—somebody who was, in one part of his being, guilty of much that is reprehensible or even criminal, and in another part of his being, capable of love and caring, even virtue. But I wanted to see how those qualities co-exist, play out at the same time.

FP: Did Stalin love Svetlana, his daughter?

SR: Well, different kind of animal, but yes. Can you think of somebody who was a good person but who wasn’t also capable of things that were extremely bad? To try to show a person who was morally “double” in some way. I wanted to see how I could do that. That was my starting point for Golden’s character.

FP: Good men do evil. Evil men do good.

SR: For sure. There’s a very funny novella, The Cloven Viscount, by Italo Calvino, in which the prodigal character is dissected by a sword on the battlefield. The two halves get sown up individually and survive. One half ends up being incredibly evil and one half ends up being incredibly saintly. And they both do equal amounts of damage. Two halves of the same man. All the virtue ends up in one half and all the bad ends up in the other half, and both are catastrophic.

FP: Regarding the LGBT community in majority-Muslim countries, do gay people represent the “decadent West” who are to be thrown from buildings, stoned, or “honor killed” by family?

SR: There is quite a substantial gay population in the Islamic world. I think there’s a lot of prejudice. People in the gay community, and certainly in the transgender community, face real obstacles. Not only in Islamic countries but even here.

I grew up in Bombay, which has always been home to quite a substantial transgender community, the Hijra. I’ve spent time in that community listening to their stories and hearing the convictions of their lives. That was for me one of the starting points in writing about an increasingly central subject of gender identity these days. Here in New York, I’ve had a couple of friends who have transitioned. One in each direction, male to female and female to male. Yes, these are people I care about who’ve gone through this process. That’s been another starting point for me.

Taking those personal elements, I tried to learn as much as I could, to explore as thoroughly as I could. When writing a contemporary novel which tries to take on the present moment, you really have to respond to the stuff that’s in the air. LGBT rights are very much in the air. I wanted to respond to that.

In India, this terrible thing happened. Under a previous government [in 2009], homosexuality was legalized, decriminalized. Many gay people came out and they lived normal lives at last. And now this new government came in, and the Indian high court has effectively recriminalized homosexuality [by not recognizing the 2009 decriminalization decision]. So that now homosexuality is, once again, illegal in India. Now all those people who came out are, in theory, at risk. That’s a very bad situation. Writers have had conversations about and have written about their own sexual orientation. Now they are now asking: can I expect a knock on the door because I am openly gay? I think it’s pretty difficult.

FP: Even if a family or friend privately wants to be accepting, the larger culture may impede that gesture.

SR: One of things that I found when doing this work with the transgender community in Bombay is that some of them had families that were accepting. Some had families that were very rejectionist. Some of them had come to Bombay, leaving their families behind, not having their acceptance. Others would go home to their family. As we might expect, there is some of one, some of the other.

FP: Sarah Schulman has made popular the work of Jasbir K. Puar, namely her ideas about homo-nationalism and “pinkwashing.”

SR: Yes, I know who Sarah Schulman is. I tried to pick up all the plot dimensions I could. What I was trying to do is make a portrait of a character who had a strong sense that maybe his gender identity either needed re-assigning or had shifted, but who was agonized about it. I wanted somebody for whom it was really difficult to consider that he might need to change his identity. Really, what I was trying to do is to get into that pain, to talk about the pain of people for whom there is no support, for whom there are very contradictory feelings and who are not clear about who they are. They feel there’s something wrong with the way in which they present [themselves], but they actually are not clear about who they are and where they wish to go. It was that confusion I wanted to enter into.

FP: That would be the richest way to portray all the elements of that situation.

SR: I hope so. I didn’t want to be judgmental or have some kind of lazy attitude. I think literature at its best is not judgmental. It doesn’t tell the reader what to think about what’s being portrayed. Literature at its best creates a world that readers enter, in which they can be challenged or provoked but in which they make up their minds about the world they were shown around. That’s what I wanted in a novel that deals with aspects of gender identity.

FP: That’s one way we might say that literature and journalism intersect.

SR: Yes, I don’t really make a big distinction between fiction and nonfiction anymore, because I think some of the work I most admire is nonfictional. I’m teaching a graduate seminar at NYU on the theme of creative nonfiction. I do think the best writing done in the last fifty or sixty years has been highly creative nonfiction, starting with the New Journalism all the way up to Svetlana Alexievich, who won the 2015 Nobel Prize for Literature. I have great admiration for the way journalists make a subject imaginatively creative for the reader. There’s a bit of me that wants to do the spadework of a journalist. I want to immerse myself in a subject and know that I know it.

FP: How do you think the LGBT community will fare under President Trump?

SR: It’s a very resilient community and it will fight back, but I think it is one of the many [minorities]that will have to fight under this administration. If indeed the administration lasts for four years, which I find difficult to believe—and then I wonder if that’s wishful thinking. Like many people, I’m anxious to see what the investigation by Special Counsel Robert Mueller brings up. Also, the rate at which the administration is melting down. It’s hard to believe this will go on for four years. Today on social media is a picture of people around President Trump. There’s Priebus, Spicer, Flynn. All of them are gone in six months. The only senior member of his staff who is still in the picture is Pence. You begin to wonder if it’s the President or Vice President who will go next.

FP: It’s like a reality show in real time.

SR: Unfortunately, that’s exactly what it’s like. Watching America turn into Celebrity Apprentice.

FP: What are your immediate fears as an individual?

SR: I’m not particularly afraid of much. You were talking about journalists as well as fiction writers. I do think the attack on the press is a very dangerous thing in a democracy. One of the things we can stand up for in America is a free press. When the most powerful voices in the land set out to undermine the free press and to shake people’s confidence in what’s presented as the truth, that is historically the first step towards authoritarianism that has been taken by dictators around the world. First you devalue the truth. Then persuade people that they can only get the truth from your mouth. Then you can say anything you want. I worry very much about attacks on the press, on free expression generally, that we have witnessed in the last six months.

FP: What are your immediate fears for the world?

SR: I hope we’ll still be here in six months. A friend said to me the other day after only six months of Trump we have people in the streets in America and we’re on the brink of nuclear war. I’d like the world to survive. I have children and want them to have a proper life in this world. Having had a long period when it appeared the threat of nuclear war was receding, it seems we’re going in the opposite direction. Having been through a long period of wanting to save the planet, we now see a regression of that, in this country, at any rate. All of that is of great concern.

FP: In honor of your sense of humor, your optimism, what are your immediate hopes as an individual?

SR: My short-term hope is that Trump won’t last, but I know that only means we get Pence. But, you know, I’ll take one asshole at a time. I do place a lot of optimism in the younger generation in this country and around the world. They are much more idealistic, a more environmentally concerned generation, one with a real sense of social justice. They also have energy to stand up to it, to protest, to mobilize, to be activists. It may be that we have to be saved by our children.

Frank Pizzoli has published interviews with many noted writers. He is the founding editor and publisher of Central Voice.