THE MOST DEVOTED FANS of a given city are perhaps the people who’ve come to it from the farthest away. Hailing from the Leave-It-to-Beaver suburbs of Cincinnati, Ohio, Edmund White arrived in New York in the 1960’s and reveled in the intellectual ozone and garrulous open-mindedness of its denizens. Meanwhile, his newly unleashed libido made a beeline for the activities practiced on the near-deserted piers and in parked trucks of Sodom on the Hudson.

In his new book City Boy(Bloomsbury), White sets his memoir of the 60’s and 70’s against the sterility of the previous decade: “In retrospect we could see that the 1950’s had been a reactionary period in America of Eisenhower blandness, of virulent anticommunism, of ‘the feminine  mystique.’ I lived through the 50’s in the Midwest when everything that was happening—the repression of homosexuality, for instance, the demonization of the Left, the giggly, soporific ordinariness of adolescence, the stone deafness to the social injustice—seemed not only unobjectionable but also nonexistent.” The shift to the 60’s is matched by a shift to a livelier, more dazzling prose: “The great triumph of the 60’s was to dramatize just how arbitrary and constructed the seeming normality of the 50’s had been. We rose up from our maple-wood twin beds and fell onto the great squishy, heated water bed of the 60’s.”

mystique.’ I lived through the 50’s in the Midwest when everything that was happening—the repression of homosexuality, for instance, the demonization of the Left, the giggly, soporific ordinariness of adolescence, the stone deafness to the social injustice—seemed not only unobjectionable but also nonexistent.” The shift to the 60’s is matched by a shift to a livelier, more dazzling prose: “The great triumph of the 60’s was to dramatize just how arbitrary and constructed the seeming normality of the 50’s had been. We rose up from our maple-wood twin beds and fell onto the great squishy, heated water bed of the 60’s.”

If the 1940’s, 50’s, and early 60’s represented the golden age of Broadway and of New York City in general, the later 60’s and 70’s marked a seismic shift as the Big Apple, facing financial bankruptcy, a crumbling infrastructure, rampant street crime, and inadequate services, seemed to be rotting at its core. For gay people in this period, it meant hanging out in mafia-run gay bars blatantly in cahoots with corrupt members of the New York Police. Yet it was arguably this very environment that supplied the irritants necessary for change. The wider influences of the Sexual Revolution, the fight for black civil rights, and the anti-Vietnam War movement also helped to fuel a spirit of activism that would flare up in the Stonewall Riots in 1969.

In 1963, on 14th Street, way off Broadway, Julian Beck and Judith Malina’s Living Theatre shocked audiences by producing the anti-establishmentarian The Brig, which depicted the dehumanizing environment to which ten American marine convicts were subjected during one day in a U.S. Marine prison. In the spring of 1964, gay author James Baldwin’s Blues for Mister Charlie (dedicated to the memory of civil rights martyr Medgar Evers) opened on Broadway. In December, 1965, Europe was represented by Peter Brook’s landmark production of German playwright Peter Weiss’ Marat/Sade, about despotism, repression, and revolution, which opened at the Martin Beck Theatre and won the Tony Award for Best Play and Best Director. The climax of the play had the inmates of an asylum in full rebellion against the authorities and spilling into the audience—a Brechtian device that would be repeated in Hair when it opened in April, 1968, a hippie-inspired rock musical featuring nudity and mockery of American jinogism (among other vices). Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band opened Off Broadway in 1968 and came out as a film in 1970. (In a tragic coda to the film’s history, five of its stars—Kenneth Nelson, Leonard Frey, Keith Prentice, Frederick Combs, and Robert La Tourneaux—would later die from AIDS-related illnesses.)

In a 2004 interview for the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care (IAPA), Edmund White, one of the founders of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, proposed: “Somebody should write a book about the 70’s—straight and gay—but it would turn out to be mainly a gay story. I feel that was one of the high points in human culture. There were all these great people—Jasper Johns in painting, John Ashbery in poetry, Balanchine’s last years in ballet, many great novelists—there was a tremendous amount of activity and a New York aesthetic that was very powerful.” He has now fulfilled that proposition in City Boy: My Life in New York During the 1960’s and 70’s, which chronicles New York’s cultural highs and lows over those two heady and iconic decades. The Sexual Revolution was in full swing; the Stonewall Riots (“the whimper heard around the world, the fall of our gay Bastille,” in White’s words) triggered the gay liberation movement; rents were easily affordable and jobs available; bohemian culture with its tradition of “honorable poverty” flourished, as did the arts as never before.

Although White has fictionalized his life in New York in some of his novels, notably the semi-biographical Farewell Symphony (1997), this new book has torn away the literary veneer to offer a straightforward rendering of the personalities and events of the period. Fictional disguises are discarded and the underlying factual pentimento revealed. And the names that are dropped! (“That’s what New Yorkiness is, primarily; the recognition of a thousand names and faces,” he writes.) The cast of characters he cites solidifies our notion of how vital a period the 1960’s and 70’s were (and, by tacit comparison, how depressingly devoid of such interesting personalities the ensuing decades have been). Since White is a born raconteur, his gimlet-eyed anecdotes about celebrities of the era are as tangy as blood orange sorbet served after lobster thermidor. So, who cares if we occasionally stray from Manhattan to visit Key West or San Francisco or Venice?

White also considers New York culture of the period from a West Coast (San Francisco) perspective and a European one, offering accounts of sojourns in Rome, Venice, and Paris. This, for example, from his time in Rome: “When I moved to Rome in 1970, I suggested to an Italian friend that we switch sides of the street to avoid confronting three teenagers coming towards us. ‘Why?’ she asked, astonished. In New York, we paid the cabdriver to wait at the curb till we were safely inside past the locked front door. We were always aware of everyone within our immediate vicinity. You never lost yourself in conversation on the street but had to be alert at all times. We made sure we had twenty dollars with us every time so that a robber wouldn’t shoot us in frustration.”

White handily captures the stoned, communal, Whitmanesque camaraderie of gay men in the 70’s, well before the trend began toward assimilation into more conventional suburban or “straight” models. “Back then, these questions of fidelity and couplehood didn’t come up and we wouldn’t exactly have known how to respond to them. Introducing the issue now slightly falsifies the quiet, natural way in which we assumed everyone would have multiple sex partners, that jealousy was definitely not cool, and that new people could be regular fuck buddies or part-time lovers, that one molecule could always annex a new atom.”

White depicts the 70’s art scene as well, including a pungent profile of bad-boy photographer Robert Mapplethorpe: “He certainly wasn’t afraid of being considered gay—on the contrary. He was interested in leather, S&M, scat, pain, blood—all the things that most gay men are careful to exclude in their list of desired activities when they write a personal ad (or now an online profile). … Mapplethorpe, like the good Catholic boy he was, believed in the devil. When he would have sex, he would whisper in his lover’s ear, ‘Do it for Satan.’ … I never understood Mapplethorpe’s sexuality. He would explain it to me and keep correcting with a little smile the wrong conclusion I’d jumped to. He’d say, ‘No, it has nothing to do with fantasy.’ Or, he’d say, ‘No, it’s not a matter of role-playing. Nothing could be realer than what I like. That’s why I like it—it’s real.’”

When White and Mapplethorpe collaborated on an article about Truman Capote for the semi-gay glossy magazine After Dark, they visited the writer in his United Nations Plaza home and found him high on cocaine. Capote told White: “You’ll probably write some good books. But, remember, it’s a horrible life.” Mapplethorpe insisted on taking a photo of White and Capote together, commenting cagily: “You’ll be happy someday that I did so.”

White’s anecdotes embrace many personalities from the New York theatre scene—Larry Kert, Mart Crowley, Robert Wilson, Gerome Ragni—as well as writers like Susan Sontag, James Merrill, Harold Brodkey, William Burroughs, and Fran Lebowitz, who “became a sort of court jester—no, that’s mean, perhaps ‘funny companion’—to different rich gay or bisexual men such as Malcolm Forbes and Barry Diller and David Geffen.” White describes the sphinx-like William Burroughs as looking like “an unsuccessful Kansas undertaker. … Usually I felt some connection with another gay man. With Burroughs, however, there was no conspiratorial wink and his sexuality seemed like something that would take place every hundred years, like the midnight blooming of a century plant.”

Beginning in the mid-70’s, White and six other gay New York writers—Andrew Holleran, Robert Ferro, Felice Picano, George Whitmore, Christopher Cox, and Michael Grumley—formed a casual club known as the Violet Quill. Meeting in one of their apartments, they would read and critique one another’s work, then move on to dessert. (By 1990, Ferro, Grumley, Cox, and Whitmore had succumbed to AIDS, as had White’s two closest friends, the critic David Kalstone and his editor Bill Whitehead.) White ends on an elegiac note: “I suppose that finally New York is a Broadway theatre where one play after another, decade after decade, occupies the stage and the dressing rooms—then clears out. … The actors are forgotten, the plays are just battered scripts showing coffee stains and missing pages. Nothing lasts in New York. The life that is lived there, however, is as intense as life gets.”

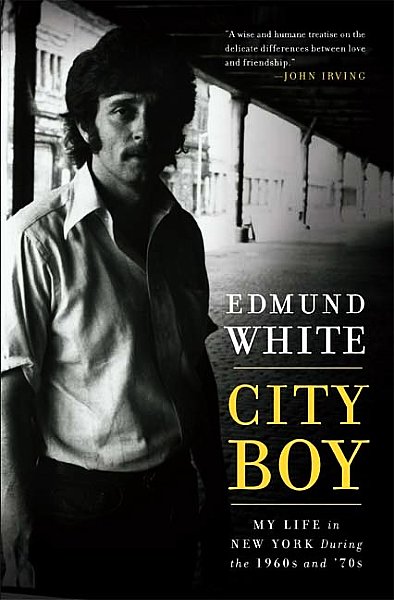

Just before we started our interview, White received a phone call from his editor asking his advice about a blurb for the cover of City Boy. It concerned author John Irving (of The World According to Garp fame), whose blurb we can now read on the front cover: “A wise and human treatise on the delicate differences between love and friendship.” On the back cover he elaborates: “I believe Edmund White is one of the best writers of my generation; he’s certainly the contemporary American writer I reread more than any other, and the one whose next book I look forward to reading most.”

Michael Ehrhardt: You look very soulful in the period photograph on the book cover, like the Knight of the Woeful Countenance. Who took the picture? Edmund White: Barbara Confino, who’s still around and has taken pictures of me recently. That was back around 1973, when my first published novel, Forgetting Elena, came out, and I had just come back from living in Rome. ME: It looks like you’re posing in the meat-packing district. EW: Yeah, that’s where the trucks were, and all the hot action at that time. It was just a half block from where I lived then. ME: In a 2004 interview for the IAPA, you proposed that somebody should write a book on the 1970’s, which was an epochal period in New York gay culture. Did you have your book already gestating at that time? EW: Well, actually I wanted it to just be about the 70’s, but then I gradually slid back into the 60’s. I soon felt I had to acknowledge the 60’s as a lead-up to the 70’s, with the Stonewall movement, to make it more comprehensive. But originally I really wanted to concentrate on the 70’s and then I wanted to end it with the advent of AIDS. I guess I had thought of doing a book like City Boy over the past; I mean, in a way, if you write autobiographical fiction the way I wrote The Farewell Symphony and The Married Man, you’re lucky, because you can also re-do it as a memoir. City Boy is actually more gossipy than anything I’ve ever written. ME: You drop the fictional disguises and name names, as it were. You were somehow right in the swim of 70’s culture, high and low. It was more of a village community then- EW: That’s right. I mean, it was more communal and social because it was cheap to live in Manhattan, and people didn’t have to work too hard to pay the rent. ME: Of course, the downside was high crime, when you had to carry mugger money. EW: Oh, yeah. Gay guys carried whistles so they wouldn’t get bashed. On the Upper West Side, you had Needle Park, which was terribly dangerous. Even here [in Chelsea]in the 70’s, when [author and critic]David Kalstone lived on this block, there were Puerto Rican gangs sitting on the stoops, people throwing bottles out of windows, boom-boxes blaring, and you tended to feel waves of hostility. ME: Needle Park is now Verdi Square; the area’s full of beauty spas, nail salons, and a Victoria’s Secret. Back in the 70’s there was also the infamous Continental Baths. EW: I used to go to the Continental, but I forgot to put that in [the book]. I should have. I mean, I went there and heard Bette Midler and I found her actually irritating, because everybody stopped having sex to listen to her. And I wanted to have sex. If you’re a sex addict, you don’t want a pop singer horning in on your scene. ME: Well there was always the St. Marks, downtown… EW: Yes, which my friend Norm Rathweg redesigned and made chic. Before that, it was seedy and dirty, run by an Armenian, with a masseur in the basement reputed to be the cannibalistic one that Tennessee Williams based his story “Desire and the Black Masseur” on. Norm also designed the Chelsea Gym and the Saint. ME: Your career as a playwright, apart from the recent Terre Haute, is not too well known. Yet you were part of the experimental playwrights working downtown, such as Jean-Claude van Italie. EW: Yes, and his lover [director]Joe Chaikin, with whom I had an affair—but I never remembered it until my love letters turned up in the library at Kent State. One of the points I tried to make in this book is that I never did anything repetitively. I would go to Fire Island, but just a few times. I’d go to the baths, but just a few times. I never went to Studio 54. I wasn’t a scene-maker, per se, and it’s only that I thankfully survived that I can write this book. But, there are probably hundreds of people who know the era much more comprehensively, but just never got around to writing about it. ME: You also write that you had a week-long affair with Mart Crowley on Fire Island. Are you still in touch? EW: No, but Don Weise, who’s the editor of Alyson Books, and is bringing out all of Mart’s plays in a single volume, mentioned that he knows me to Mart, and Mart would like to see me again. By the way, Mart had the biggest cock I ever saw. ME: Considering your sexual exploits during that era, it’s hard to imagine you could hold down a job at Time-Life and at McGraw-Hill and still have time to write plays and novels. Were you on amphetamines or something? EW: That was in the 60’s. I had put on some weight—I was always yoyo-ing with my weight—so I went to a doctor who prescribed speed. You could lose fifty pounds in a month. Of course, I was young and my heart was good, and so what if you didn’t sleep for a week? ME: But, obviously, you had the ambition to follow through. A lot of people would have hit a wall with writer’s block. EW: I could never afford that. I was trained as a journalist, too. And with that training you have to write to deadline; you can’t afford to be word proud, because people are always editing you. But I’ve always been very productive; and yet I’m one of the most disorganized persons on earth, completely distractible; yet, I’ve written 22 books. In the last twelve years I’ve written a book a year. I don’t use the computer very much—I’m writing my new novel by longhand. Anyway, I’ve always been broke, so I write partly for money. ME: At least you’re in the position of a world class writer, so that you have more chances when giving a proposal for a book, right? EW: Well, you’d be surprised. For City Boy, my regular editor at HarperCollins rejected it. And now I want to do a sequel to it, about Paris in the 1980’s, which is when I worked for Vogue for eight years at the height of the fashion period. ME: Then you knew Leo Lerman [editor at Condé Nast Magazines]? EW: Sure I did. He knew everyone. Actually, I found him ten percent dull. I don’t know what I could say about him, except that he was a great tastemaker, that he was prematurely old, that he had the world’s largest collection of glass paper weights, he had a very handsome lover, and a mammoth apartment catty-corner from Carnegie Hall. What else can you say about him? That he knew everybody who was relevant then in the arts. ME: Did you ever meet Lincoln Kirstein? EW: No, I never met him. I just read the wonderful Martin Duberman biography about him. He really was psychotic—in and out—but he achieved such great things, from Hound and Horn [a literary quarterly he co-founded at Harvard]to the New York City Ballet, and is the sole reason we have it today. ME: You knew William Burroughs. Was he a sort of literary grifter putting on a pose, or was he really as alien as he seemed? EW: Maybe, partly. I met him around 1978, and he really didn’t talk much, except once over dinner he explained if he wanted to write about sex, he wouldn’t jerk off for several days, until he was horny enough to do so. In later years, we did correspond rather frequently. Burroughs came to Paris when one of the last social events Michel Foucault organized was a dinner for him, with about thirty persons. But Burroughs was so stoned that he was incomprehensible. What amazed me was that so many straight guys revered Burroughs and [Allen] Ginsberg. I once met a straight guy who put out for Ginsberg, and when I asked him why, he said: “Man, he was Allen Ginsberg, man!” ME: What was Foucault’s interest in Burroughs? EW: I don’t really know. We really didn’t discuss it. You know, he’d oftentimes get dragooned into that role, because he was the most famous person in France after the death of Sartre. I think he’s much more interesting than Sartre, and I think his work will live forever. ME: Do you find the work difficult or sometimes contradictory? EW: Maybe the early stuff is difficult, and he once said to me, “Have you ever wondered why my writing’s gotten simpler as I lived on?” And I replied, “I guess so. Yeah, why?” And he said, “It’s because I’ve learned how to write. When I started writing, I didn’t know how to write. And so all the earlier books, like The Birth of the Clinic and even Madness and Civilization, are really hard to read because I didn’t know how to organize my material and express it clearly.” But The History of Sexuality and the other works are totally lucid. And the weird, sick thing is that in France he was criticized for those books being too clear! ME: When I say that Foucault’s difficult, I mean, for instance, his position on gay identity was ambiguous. He was against the culture of self-avowal. Isn’t that an existential conundrum? EW: No. You have to link it to French universalism. The French are very opposed to identity politics in any of its forms. There’s no Jewish, black, Muslim, or gay novel in France. Everybody denies and dislikes those categories, and they see it as a curtailment rather than an enhancement of human freedom. I feel French universalism was a very progressive thing—in the 18th century. In the light of the French Revolution, this was a tremendous advance in saying that all people are equal in the eyes of the state and the law. After all, revolutionary France was one of the first places to declare the Rights of Man for blacks. ME: And you also knew Charles Henri Ford, who was, in turn, connected to Kirstein and Balanchine through the Russian painter Pavel Tchelichev, who was Ford’s lover. EW: Yes. I have a funny anecdote about Charles Henri Ford. I met him for the first time in Crete, where we were both renting houses, and we shared a secretary, who was a nice Irish woman who introduced us to each other. This was in the early 80’s, when Ford was already quite old. And he lived on the Île St. Louis, where I also lived, so we were on the same circuit. Once I told him: “I know something crucial and interesting about you that you don’t know.” Ford was curious to know, and I explained: “In 1942, you wrote a letter to Tchelichev saying that you had a wet dream about him the night before. And Pavel’s English was so bad, he didn’t know the expression. He thought you meant ‘wheat dream.’ And he did a famous portrait of you with your face superimposed on a field of wheat.” He was absolutely astonished. The reason I knew that was because I was very close to Simon Karlinsky—whom I mention in my book—who was head of the Russian department at Berkeley and a friend of Nabokov’s, who was doing some research on Tchelichev. And being a Russian speaker himself, he was stumped by the expression, and he put all that together himself. ME: It seems it was a lot smaller world among artists and writers then. More collegial? EW: Oh, yes, it was. Fran Lebowitz once said that everybody who reads Interview magazine, and was interviewed, knows each other. They all knew Andy. That was true back then. ME: You tell of the nearly suicidal angst you suffered on getting your first book, Forgetting Elena, published. And then you followed up with Nocturnes for the King of Naples. It’s amazing that you persevered with writing these novels, when you weren’t sure if you had a snowball’s chance in hell for getting published. EW: Well, Nocturnes came out in ’78, the same year a lot of gay novels came out, like Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance, Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, and Larry Kramer’s Faggots. That was almost ten years after Stonewall, but it took that long for people to gear up to publishing gay fiction. ME: Do you feel that gay lit has been pretty much been subsumed into other media, particularly TV, and a whole cosmos of indie films constantly being churned out? EW: That’s true, to some extent. But, there’s always got to be room for stories. In fact, TV and movies cannibalize fiction. I believe that fiction remains the most ambitious account of how we live now, because it includes subjectivity, which movies and TV cannot, unless you have voice-overs, but those never work out. I mean, most of us live inside our heads, and we’re constantly evaluating the situations around us. We act, but not that much. Consider that many movies are about people with guns, while I don’t think I’ve seen more than two guns in my lifetime. Most movies are about something that doesn’t really happen to ordinary people, and what does happen, which is living in your head and processing your own experience, does take place in fiction. So, if you’re interested in reality and how to understand it, fiction’s the place to go. That’s my commercial for fiction. ME: True, it’s hard to imagine Proust on film, though it has been attempted. Yet we’re assuming a younger generation of readers is there, in a so-called post-Gutenberg era. EW: Well, people have been claiming that for fifty years. Actually, more books are sold now than ever before in history. And there are so many different titles, and so many niche markets. So if you’re interested in, say, Wagner and sadism, you’ll probably find a book about it, and if you’re interested in race car drivers and their illicit affairs with midget women, you can find books about them, too. Because of blogging, people now are very used to reading and writing and “journaling.” Creative writing classes now have bigger enrollments than ever before. ME: Also, the Internet has made everyone a critic. Amazon solicits book reviews. You mention once or twice in your book that when The New York Times reviewed your first novels it was important, since they could make or break a book. You don’t think it has the same clout today? EW: No. Perhaps some, but not that absolute stranglehold that it used to have. ME: You had an off-and-on friendship with Susan Sontag, which you write about. You sort of demystify her for readers. EW: Did you think so? I didn’t think it was mean-spirited. ME: No, I think you humanized her. Less of a monstre sacré. But it was interesting to read how careful and studious she was about stage-managing her career and public persona, and about not being openly gay. EW: Well, coming out is still a bad career move. Everybody is going to howl at me for saying so, but I think it’s easier for women like Ellen DeGeneres or Rachel Maddow to come out [than for men], who are very attractive and who all women respond to. Both of those women have a great appeal and charm. ME: Getting back to the subject of gay lit, you write about Christopher Isherwood. His novel A Single Man, published in 1964, is arguably one of the first openly gay novels that isn’t camp or tragic, as opposed to Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room or Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar. Would you agree? EW: Giovanni’s Room is weird, because it’s written by a black man, but there are no black characters in it. I mean, it seems like the idea behind it is that men are desirable as long as they’re straight, but the minute they go to bed with you they become sisters, and therefore they’re bad, like trash, and all you can do is bump pussies with them. I remember when I came out in the 50’s that’s what people thought. And Baldwin just echoes that. Then there’s Vidal’s book, which is camp, with lots of campy dialogue. ME: So, you’d agree that A Single Man was an early avatar of the positive gay novel? EW: Yes, a hundred percent. And why was it so ahead of its time? I’d say because Isherwood was part of the original gay revolution in Berlin and actually lived in Magnus Hirschfeld’s house. Isherwood had tremendous class confidence, and he lived during the war years and afterwards in California, which is one of the great breeding grounds for modern homosexuality, and got all the fall-out of the GIs coming back from the war. Many GIs came out around that time. The army was a great breeding ground for modern homosexuality, because you had all these young men, who were far from home, who thought they would die any day, who were all thrown together in the barracks, so why not seize the moment? And a lot of those guys settled in the beach communities of California after the war, because they didn’t want to go back to Pittsburgh and get married to their childhood sweethearts. ME: Isn’t that what a lot of the phobia is about “Don’t ask, don’t tell”? EW: I think there is a lot of homosexuality in the Army. But I have a theory which you can agree or disagree with, that before homosexuality became so public, so vocal, and so politicized, there was a lot more casual action than there is now. I think that between AIDS and then the high profile of it, it discourages people from experimenting. I mean, I’m old enough to remember the old Mediterranean world of Greece, for instance, where almost any man, if you paid him something, was readily available.