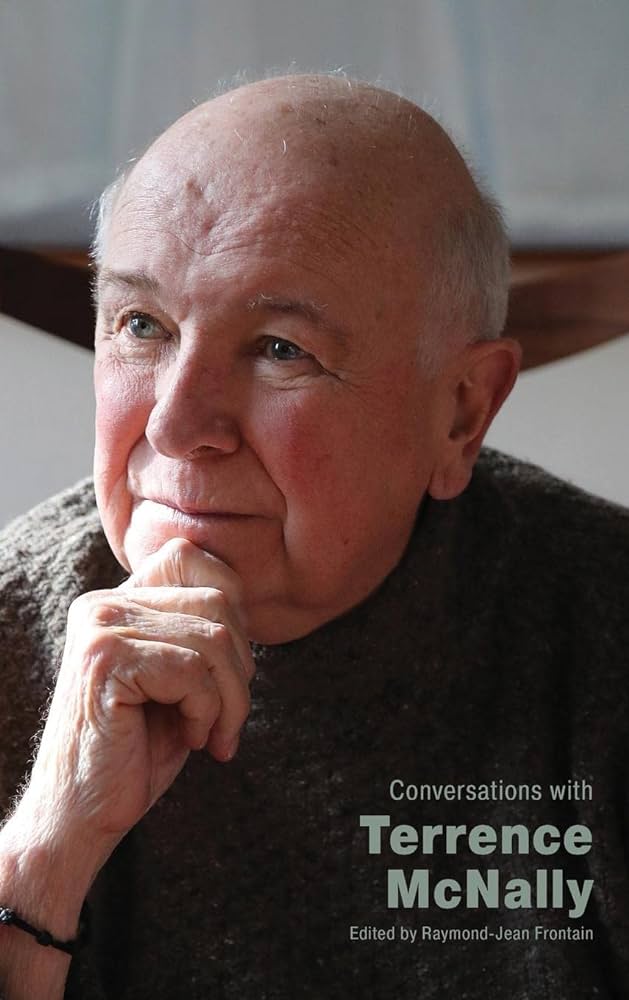

CONVERSATIONS WITH TERRENCE McNALLY

CONVERSATIONS WITH TERRENCE McNALLY

Edited by Raymond-Jean Frontain

Univ. Press of Mississippi

208 pages, $25.

DURING HIS LIFETIME, Terrence McNally saw seventeen of his plays and musicals premiere on Broadway, and along the way he developed a tenacity and maintained a relevance that has eluded most American playwrights in their later years. Conversations with Terrence McNally, edited by Raymond-Jean Frontain, helps to illuminate a writer whose work has not always shown up on the literary radar of critics and tastemakers.

Within these nineteen interviews from 1974 through 2018 (McNally died from Covid-19 at age 81 in March of 2020), there is naturally some repetition of his origin story and certain incidents that serve as landmarks in his development as an artist. Especially memorable is when his parents in Corpus Christi, Texas, decided to listen to Saturday afternoon football games in their car so that adolescent Terrence could hear the Metropolitan Opera on their good radio, direct the operas on miniature cardboard stages, and turn the volume up as loud as he pleased.

While the most famous gay playwrights of the 1960s—Tennessee Williams, William Inge, and Edward Albee—remained professionally in the closet, McNally never hid his homosexuality. In McNally’s first Broadway play, And Things that Go Bump in the Night (1965), one of the main characters, Sigfrid, is a gay man whose sexuality is not a driving factor in the story, but who does go home with a man he meets in a park. Such normalizing of a queer character was radical for a commercial Broadway production at that time. One outraged critic wrote: “It would have been better if Terrence McNally’s parents had smothered him in his cradle.” Sigfrid was but the first in the gallery of McNally’s openly gay characters, most of whom do not suffer because of their sexual orientation but instead cope with life by searching for connection with others.

Because of the persistent presence of his unapologetically gay characters, theater critics have been inclined to refer to McNally as a “gay playwright” or to marginalize him as “the spokesperson for gay writers.” McNally rejected the moniker “gay playwright” in interview after interview, insisting that he was a writer who happened to be a gay man. For McNally, the distinction was meaningful, though he never shirked from acknowledging his sexuality. In a 1997 interview, McNally split the difference: “I’m always accused of saying that I’m not a gay playwright. I’m not saying that at all. I’m a gay man who is a playwright. It’s not just about my sexuality.” McNally never wavered in his insistence that his sexual orientation should not be used as a way to define him as a writer.

This typecasting further perturbed McNally when it came to assumptions about the political nature of his work. “The play Lips Together, Teeth Apart was reviewed as a politically incorrect gay play because I enforced every stereotype … that gay men have promiscuous sex because the guys are having sex in the bushes. Well, gay men have sex. One of the ways you are gay is having sex with another man.” Addressing the often presumed obligation to be the mouthpiece for a cause, McNally added: “I don’t write plays to do service to gays, but I certainly don’t think I’m doing them a disservice either. Theatre is not about writing role models.”

During the first fifteen years of his career, McNally was known primarily for writing political plays and some comedies—most memorably The Ritz (1975), a successful farce that takes place in a gay bathhouse. He began to branch out in 1987 with Frankie and Johnny at the Claire de Lune (McNally’s most performed play), a two-hander about a straight man and woman that, according to McNally, “[e]xamines intimacy and what people who are over forty do about having a relationship. … It’s about love among the ashes.”

With respect to the diversity of his characters, themes, and styles, McNally declared: “I would like to have it said that there is no typical play by Terrence McNally.” In these interviews, he reflects on that variety when he speaks about the public reception of his plays, such as the polemical Vietnam drama Where Has Tommy Flowers Gone (1971); the story of two older women who find their spiritual selves during a trip to India in A Perfect Ganesh (1993); the biting drama of a group of Long Island elites who refuse to swim in a pool after a man who died of AIDS had used it in Lips Together, Teeth Apart (1991); his investigation of the creative process as embodied by Maria Callas, Master Class (1995); his hilarious and compassionate look at a group of gay men living through the AIDS epidemic in Love! Valour! Compassion! (1994); and his contentious recasting of Jesus and his disciples as a group of contemporary gay men in Corpus Christi (1998). The uproar from right-wing and evangelical organizations about the latter prompted his long-time collaborators at the Manhattan Theatre Club to announce they had pulled the production. After an even louder outcry from the theater community, it was produced by MTC with a phalanx of protestors outside the theater every night of the run.

In 2017, McNally published Selected Works: A Memoir in Plays, an anthology of eight plays with essays by the author that provided context for each play’s original production and what inspired him to write it. In all, he wrote 26 full-length plays, over half a dozen one-acts, four teleplays, three films, and four operas. Also a gifted librettist, McNally wrote the books for ten Broadway musicals, including Kiss of the Spider Woman and Ragtime. His only work-for-hire experience was the book for The Rink (1984), after which he decided to work only on musicals as an original collaborator.

McNally held no romantic notions about the workaday aspects of his career. “You learn there’s nothing precious about writing, it’s a job like any other.” And as for the art of playwriting, “[It’s] a craft, and if it’s good, it’s an art, but it’s not some mystical thing. Writing plays is very practical. Theatre is the most practical art form I can think of.” This speaks to McNally’s work ethic, but leaves out his passion: “Write plays that matter. Raise the stakes. Shout, yell, holler, but make yourself heard. It’s for playwrights to reclaim the theatre. We do that by speaking from the heart about the things that matter most to us. If a play isn’t worth dying for, maybe it isn’t worth writing.”

As a reward for writing from his heart, McNally had shelves and walls full of prizes—five Tony Awards among them—and accolades, including his election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2018. Yet the recognition he was most proud of was when Matthew Lopez told the press that his hugely successful play The Inheritance could not have been written without “the influence of Terrence McNally’s lifetime’s work.” Sharing the story with Frontain, McNally declared: “It’s the greatest honor I’ve ever been paid.”

The best advice McNally ever received? “I learned from Elaine May that playwriting is about what characters are doing, not what they’re saying.” For a man who made significant contributions to modern theater, Terrence McNally’s impact has not yet been fully appraised. One thing that these interviews make clear is that within the pantheon of American playwrights, McNally was a modest person and a serious artist who remained unpretentious to the end.

Thomas Keith contributed a chapter on Robert Burns and Frederick Douglass to The Oxford Handbook of Robert Burns (2024).