ONE OF THE INSPIRATIONS for this issue’s theme was a recent book by Jeffrey Escoffier titled Sex, Society, and the Making of Pornography: The Pornographic Object of Knowledge(Rutgers, 2021, reviewed in this issue), much of which focuses specifically upon gay male pornography from the postwar era up to the 1970s. As the book’s title suggests, Escoffier is not looking at porn in a vacuum but in relation to changes that were taking place in sexual behavior and attitudes in society at large—changes that were indeed revolutionary in their sweep and rapidity.

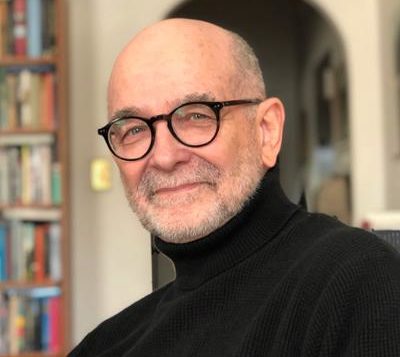

Jeffrey Escoffier has a long history of LGBT activism and scholarship. He cofounded two important LGBT magazines— The Gay Alternative, in 1972, and out/look, in 1990—and cofounded the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project in 1977. From 1995 to 2015, he served in the NYC Dept. of Health and Mental Hygiene as deputy director of the Office of Gay and Lesbian Health and the director of the Health Media and Marketing Group. His other books on sexual history in the U.S. include Sexual Revolution(2003) and Bigger Than Life: The History of Gay Porn Cinema from Beefcake to Hardcore(2009).

This interview was conducted by phone in early November.

Gay & Lesbian Review: So, we’re putting together this issue with the theme of “sexual awakenings,” about the origins of gay sexual culture in the postwar era. Your new book deals with precisely this period, tracing the origins and development of sexually-oriented movies and especially gay pornography. The key chapter for our purposes is titled “From Beefcake to Hardcore,” which traces the arc from the physique magazines of Bob Mizer in the 1950s to the full-penetration movies of the early ’70s. Maybe the signal moment was when the performers went from being models and actors to being essentially sex workers. What made that transition possible?

Jeffrey Escoffier: Well, a couple of things are going on at the same time. One is that in the mainstream culture, there’s a shift toward more sexual frankness in general. A lot of that was driven by changes in the legal status of pornography. Straight porn was going through a major shift, from softcore, which featured female crotch shots (the so-called “beaver films”), and then to more explicitly open legs, and eventually hard penises and penetration. Gay porn moved along at roughly the same pace. Bob Mizer and the “physique” magazine people were also beginning to film hardcore, though it wasn’t shown in theaters. It was mostly sold directly to individual subscribers. That was all happening at around the same time. It became possible to make porn if it had an alibi—some kind of “socially redeeming importance,” following the 1957 Supreme Court ruling [Roth v. United States], which basically just meant that you had to have a plot.

G&LR: That sets the stage for how we go from the beefcake and the physique magazines, which are softcore, to the beginnings of hardcore in the early ‘70s.

JE: Actually, it almost happened overnight. It was in 1969 that the first straight hardcore porn was shown in a theater in San Francisco. At around that time, gay porn made the same transition.

G&LR: Which happens to be the same year as Stonewall. Obviously, a lot was happening culturally at that time. You circle back a number of times to the idea of “sexual scripts” as central to the creation of porn. This seems to be especially true in the early days, when there had to be a “socially redeeming” story. But a script means something different in porn than it does in a mainstream movie. You talk about how these scripts came from a variety of different sources. Where are these scripts coming from? Where are people getting their ideas for the early porn?

JE: It’s interesting because the whole notion of a sexual script originated in this period. It was a theory developed by sociologists John Gagnon and William Simon, working at the Kinsey Institute. It was partly a shift from thinking of pornography, or sex in general, as something that’s not strictly biological but is also culturally and socially shaped. Every one of us in any of our sexual encounters has some sort of story that we’re acting out, whether it’s a love story or a sexual fantasy. In pornography, there are scripts at a number of different levels. One is just at the level of every individual who engages in sex having some sort of script in their head that they’re trying to act out. Basically, when you have a sexual encounter, the two of you are working out a script together. Pornography draws on that fact, that social fact. We all have sexual scripts that we’re basically playing out. But a lot of different people have a hand in pornographic scripts—the editor, the director, as well as the participants. One of the strange things about pornography is that it doesn’t seem to be very interesting or convincing to us unless actual sex takes place. In a murder mystery, there doesn’t have to be a real murder. But in a sex film, there has to be real sex. I feel like the beefcakes were really about admiring beautiful male bodies, but the hardcore films are actually about gay male sex.

G&LR: You also point out that the actors in porn are active agents instead of just being passive objects of desire, as they were in beefcake. Now they’re doing something and interacting with each other, engaging in an activity that you were never told about in school.

JE: Yes, I just know for myself, when I was in my twenties and I saw one of my first pornographic movies—it was kind of a homemade film by an artist who wanted to make art films that showed someone being fucked with an erection and ejaculating—I thought I had never imagined anything like that. That suddenly seemed to me a very vivid kind of sexual thing that I had not encountered in my very limited young life, and this was well before Stonewall.

G&LR: You raise an old question about the relationship between culture and art. On the one hand, these scripts seem to reflect what people are actually doing in the real world, but they’re also shaping how people thought about sex and giving them ideas about what to do in bed.

JE: I think that for gay men—and this is probably more true for gay men than it is for straight men—pornography was a very important thing for us, because we learned things about sexuality that we would not have gotten any other way. We didn’t have brothers and fathers talking about their gay sex to us. You had to figure it out for yourself.

G&LR: Another issue that you raise is that of gay identity. You point out that in early porn the guys onscreen, whether they’re highway hustlers or Kansas City truckers, are not identified as “gay men.” Indeed sometimes they’re expressly identified as straight men who just happen to enjoy sex with other men. In a way, that seems not very liberating. But you also point out that just witnessing these sexual activities gave them some legitimacy to viewers. In this way they played a role in the formation of a gay identity for many men.

JE: What’s interesting about that period was that, before Stonewall, sometimes you weren’t sure whether you were straight or gay or whatever. So you ended up having sex with people who might have been interesting. You experimented, but not much more. I think that exists nowadays even more than it did throughout the ’70s. I have younger friends who talk about having sex with their straight friends or even having threesomes with a straight friend and a girlfriend. There’s still a lot of talk about trying to figure out exactly what it means that you’re doing this, whether you’re gay, straight, bisexual, or what. I think it’s that period and that idea of not having a firm identity. I know for myself, my sexual preferences have changed over the course of my life. I’ve had crushes on women; I had this period when I was very attracted to young butch lesbians.

G&LR: Something that I’ve thought about before: is there a sense in which the wheel has come full circle? I’m old enough to remember the ideology back in the early ’70s was that we’re all basically bisexual; we are simply sexual beings. Nowadays young people resist labels and the whole idea of a fixed identity, and we talk about sexual fluidity. Do you think the arc has come full circle?

JE: I do. I have a young friend who told me how he identified as gay by watching pornography, because at first, he was only interested in the men. But now he’s having sex with women and men, and the men he’s having sex with are sometimes straight, sometimes gay. So there’s a lot going on. He’s always saying: “Well, am I gay?” He’s also kind of femme. Does this make him trans? These questions are out there, and I personally think it’s a good thing. I had a ten-year relationship with a straight man who was a gay-for-pay porn star. It was a great relationship, much better than my last gay relationship.

G&LR: Perhaps the idea of not having a fixed identity served us well in the struggle for equal rights, but now we have the luxury of going back to a more fluid concept. One thing you mentioned along these lines is that a lot of the performers in gay porn are straight— I think you said it could be forty to sixty percent.

JE: This was in the ’90s when I was working on my book. I asked people in the business, like the directors and producers, who would report these numbers. In my travels I met lots of men who identified as straight but enjoyed getting fucked. This shows me that sexuality is a much more fluid thing than the concept that you’re either gay or straight. Those identities are much less sharply drawn nowadays.

G&LR: We haven’t actually talked about the filmmakers themselves, such as Wakefield Poole or Joe Gage. How did they get their start? You talk about the fact that gay men were frequenting straight porn theaters in the late ’60s before there was gay porn, so it seems there was an existing niche just waiting to be filled. But someone had to take the first step.

JE: Wakefield Poole died very recently. He tells a story of going to a porn theater with some friends of his. They would go just as a lark, mostly. The lights were on because the police would be raiding the place and looking for people having sex. The porn was so boring that there was even someone reading a newspaper while the movie was showing. He and his friends fell asleep, and he thought that he could make something better, so he made Boys in the Sand [1971], basically with a home camera and a few thousand dollars.

G&LR: You also discuss the documentary aspect of gay porn, because there’s this element of realism. They’re low-budget films, and they’re being filmed in real places, like people’s bedrooms, so you can get a flavor of what gay life was like. You talk about that and how it’s possible to go back and look at these pornos to figure out what was happening in gay culture and gay life in the background.

JE: Well, gay pornography is only archived in a few places, among them the ONE Institute in Los Angeles and the San Francisco GLBT Historical Society. But I think pornography is also a historical archive and tells us something about the flavor of the times. That’s one of the things that I’m interested in. In some ways I’m more interested in the history of sexuality than in the history of pornography.

G&LR: The second half of your book is about the production of porn. We learn that there’s a lot of artifice even though it may look like people are just having sex. People think you just let the camera roll and voilà, but of course it’s much more complicated. The action is highly scripted, and there’s a lot of editing. I think you said it might take six hours to produce a fifteen-minute scene. So, how much can it really tell us about what people were doing sexually in the real world?

JE: You’re right. That is the difficult question. In the essay on sex in the ’70s, I try to think about that a little. I don’t think there’s one solid rule that you can follow that makes it totally clear. What’s interesting about the early stuff shot in New York is that sometimes it was shot in a bathhouse, sometimes it was shot at the Hudson River piers, and sometimes at a fictional setting. I don’t really have a hard-and-fast rule for evaluating the level of realism. You just have to judge. It’s one of those things that you kind of know when you see it. You can just tell because of the low-budget aspect that the real world is just creeping in. Here’s a guy who needs to make a few hundred bucks and he’s really a straight man. Often they look like hippies, this being the ’70s. They have long hair, and you know that the counterculture is going on in the background. You can infer a lot from that.

But on the question of what men were doing sexually, there are a couple things about the history of sexuality and gay men that I’d like to bring up, because I don’t really know the answer. First, there’s lots of evidence for a sexual subculture flourishing before Stonewall. Second, one of the big questions that I think is very historically significant was raised by filmmaker David Weissman, who’s doing a series of interviews with gay elders. He asked me this question: “Was there a shift from oral sex to anal sex at some point?” I think there was, and I think it took place either during or right after World War II. I think some of it had to do with how people lived. If you lived with your family, it was much more likely that you were going to have a lot more oral than anal sex. You have to have a comfortable or a secure kind of place to have anal sex. I know in less developed countries, anal sex is always an issue for people needing a private place. A lot of oral sex took place in public before Stonewall, so that was a big shift. That’s important because anal sex was one of the main reasons that AIDS spread so quickly among gay men. Not only that, but also because people went back and forth.

G&LR: Right, because people didn’t identify so strongly as tops or bottoms. There was more “flipping.”

JE: When I was a young man, it was part of the etiquette of gay life that you didn’t insist on topping or bottoming. I think that’s a key issue in a sexual history of gay men. But there isn’t a lot of evidence. I asked Martin Duberman, and he said: “Oh my God, it’s always been anal sex.” Yes, but I just don’t believe that it was that common. And I have heard of lots of other things and seen lots of other evidence that suggest that’s not the case. Even in A Night at the Adonis, which portrays sex at the Adonis Theater, most of the sex is oral, though there is some anal sex, to be sure. Certainly in public, oral is just a lot easier. I just think this is interesting. What is the dominant paradigm of our sexual scripts, anyway?

G&LR: I remember chuckling when I read in your book that a movie that was filmed at the Adonis and titled A Night at the Adonis was then shown at (where else?) the Adonis Theater. That’s getting pretty “meta,” isn’t it?

JE: It gets better! At the moment I’m working with a friend on a musical version of A Night at the Adonis. It has a script at this point that’s just a draft. It will include some of the real-life background about the making of the movie. Stay tuned.