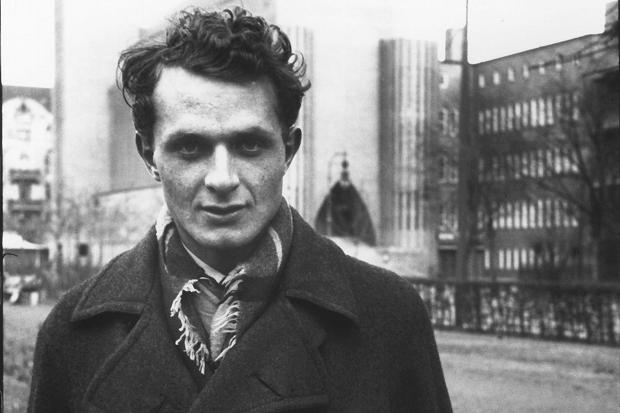

DAVID PLANTE is an Anglo-American writer who is perhaps best known for a trilogy of autobiographical novels—The Family, The Wood, and The Country—that were joined together in a 1983 edition under the title The Francoeur Novels. He has had stories published in The New Yorker, which is like having an Order of Merit conferred on any writer. Plante has also written nonfiction works, among them the well-received personal narrative Difficult Women: A Memoir of Three (1983), an account of his relations with Jean Rhys, Sonia Orwell, and Germaine Greer. He has just come out with a new memoir, a sequel to his 2013 book, Becoming a Londoner: A Diary, which a piece in The London Review of Books makes sound like highbrow literary gossip with the young Plante, a newcomer to the British capital, hanging on to the remnants of the Bloomsbury circle—figures like poet Stephen Spender—as if to bask in their glow by sheer proximity.

Coming out of devoutly Catholic French-Canadian working-class stock, Plante was one of seven brothers. Raised in Providence, Rhode Island, he left in the 1960s and took up the life of an expatriate littérateur, heading first to London. His adventures there are described in the 2013 book. The new memoir, Worlds Apart, picks up with his extensive travels and living stints elsewhere in Europe (France, Italy, Greece, Russia) and in the U.S. (mostly in New York). The structure of the book is not chronological but thematic, drawing from the vast archive that is his lifelong diary, which documents fifty years of his life in many thousands of pages.

Plante’s new memoir is populated by famous artists and writers whose private lives he knew about first- or secondhand, including that of Spender, whom Plante had actively sought out in London and who soon became his close friend and mentor.

Still, if all this suggests something heady and artificial, a roundelay of exhibition openings and book-chat cocktail parties, that would be mistaken. For if we look past the large reputations trading bon mots at dinner parties, what this memoir achieves is a portrait of a sometimes difficult “marriage”—David’s to Nikos—operating within a particularly sophisticated universe where friendships and sexual peccadillos went hand in hand.

Early in the memoir, in a chapter set in New York, David reveals his friendship and comfy sexual relations with the painter Jennifer Bartlett. When Jennifer is planning a trip to London, David frets over whether or not to extend an invitation to her to stay with him—and, presumably, Nikos. Nikos finds out that Jennifer and David are communicating about this, and he admits that he’s furious about “intrigues behind his back.” Unbeknownst to David, an architect friend, Max Gordon, has already asked Jennifer to stay at his place. Gordon tells David that all his friends know his “weakness for … strong neurotic women. Jennifer herself knows it, and we’ve got to protect you from your weakness. … And it’s very unfair to Nikos. I told her that as well.” Later in the memoir, Plante’s weakness for strong neurotic women is amply illustrated when he and Germaine Greer, the witty and voluble Australian feminist who was a talk show staple in the ’70s, share a house while both are teaching at the University of Tulsa. Greer’s abruptness could test many a less self-assured personality, yet Plante takes her in stride.

Although jealousy is a continuing motif in Plante’s portrait of his and Nikos’ “marriage,” on the surface the two men seem to agree that each is free to have outside relations. Yet David in particular seems unhealthily suspicious that a colleague with whom Nikos once had relations is still a threat, despite all assurances to the contrary. Fortunately, David’s appreciation and love for Nikos—and the sense that their carnal relations are satisfying and emotionally resonant—is portrayed with tenderness and an awareness of the complexities, the occasional pettiness, and the eternal mysteries of coupledom.

Although jealousy is a continuing motif in Plante’s portrait of his and Nikos’ “marriage,” on the surface the two men seem to agree that each is free to have outside relations. Yet David in particular seems unhealthily suspicious that a colleague with whom Nikos once had relations is still a threat, despite all assurances to the contrary. Fortunately, David’s appreciation and love for Nikos—and the sense that their carnal relations are satisfying and emotionally resonant—is portrayed with tenderness and an awareness of the complexities, the occasional pettiness, and the eternal mysteries of coupledom.

Balancing the intermittent accounts of this sometimes fraught union spread over holidays and rustic country homes, first in Italy and then Greece, are noteworthy chapters on Stephen Spender and his wife Natasha, along with Plante’s friendship with Philip Roth in the years of Roth’s London residency and marriage to the legendary English actress Claire Bloom. Roth, who early in his career was the author of Goodbye, Columbus and Portnoy’s Complaint, was already a writer whose literary reputation far exceeded Plante’s, and his heterosexual bona fides hardly needed confirmation. Yet in Plante’s characterization, the reader finds himself warming to Roth, who expresses curiosity about his friend’s gayness and embraces him affectionately—plus there’s Roth’s exuberant Jewishness and his Borsht Belt sense of humor, notwithstanding his occasional contrariness, as evidenced when the two tour Israel together.

At lunch one day at Roth’s London club, Roth admits to being “culturally lonely” living in Britain. He suggests that Plante take up this large question in his next novel: “What is your quarrel with America?” Roth then dictates a series of questions to David that might as easily have been David’s questions to Roth: “When did you discover that you were not a member of the great country, but a minority?” and “What were you most ashamed of? … Which of your relatives most embodied the shame?” and “How did you think your possibilities were limited by background?” and “How do you think your expatriate status is a direct outcome of your tremendous cultural marginality?”

Plante’s “Canuck” identity, more than his being gay, seems to have been central to his sense of self, and the marginality of Americans descended from Québécois ancestry remains an especially painful wound. Plante’s visits home, especially when each parent dies, reveal this private, hidden scar beneath his external worldliness. Indeed, after a heady dinner party in New York at which the now married Jennifer Bartlett is present, Catholic novelist Mary Gordon walks with Plante in the East Village. Plante talks about “moments of embarrassment when you recall you did something … [t]hat made you think you had been and were still a fool.” Gordon ascribes such feelings to “class” and shares a further insight with Plante, her literary and Catholic compatriot: “Those moments of recollected embarrassment come to us because we’re working class.”

Plante’s account of the aging Spender, a perennial absent-minded professor type, and the somewhat forlorn Natasha, aware of her husband’s sexual penchant, is at once touching, endearing, and

perplexing. We might consider that in 1993-94, when the young American novelist David Leavitt published While England Sleeps, a fictional account of Stephen Spender’s Spanish Civil War episode with a man he called “Jimmy Younger,” Spender railed against Leavitt for having used his own 1951 autobiography, World Within World, as the basis for his novel, charging copyright infringement. More to the point, even though the book was offered as a work of fiction, the aging poet was furious about Leavitt’s sexual explicitness. He wrote in a 1994 letter to The New York Times that Leavitt had added a new, distorting dimension to World Within World by introducing into the story of an upper-class English writer and his working-class friend lubricious accounts of homosexual lovemaking between them. … I resent my biography being mixed up with David Leavitt’s pornography. … [I]f he wanted to write about his sexual fantasies, he should write about them being his, not mine, for by his use of my copyrighted book, his central narrator was made clearly identifiable.

In Britain at least, Leavitt was raked over the coals and the original version of the book withdrawn, forcing an expurgated version to be produced.

Without going into the weeds of this literary scandal, we can be sure that Spender was not one to “let it all hang out.” Thus, it strikes me as curious that Plante exposes Spender’s ongoing, long-distance romance with Bryan, a much younger American student of his, in some of its most intimate dimensions. The publication of the student’s letters to Spender, to which Plante had access, hints at confidences betrayed, especially if we consider that Spender had arranged for his American boyfriend to send his correspondence poste restante to David and Nikos in order that Natasha not discover the evidence of her husband’s deep and continuing love affair. Of course, had we not the evidence of these letters, the young man would have remained a shadow figure; the few quoted letters show him to be mature beyond his years, thoughtful and precise, even elegant in his expression, and genuinely in love with Spender, who was surely old enough to be his grandfather. In light of the earlier Leavitt scandal, it begs the question if Plante had some agreement with Spender about using them for publication.

Late in the book, Plante recounts a phone call from Spender, whom he had “never known … to weep.” By this time, Spender and his American friend were no longer lovers, though each remained emotionally loyal to the other. Bryan had died of AIDS. Confided Spender to David: “I loved him more than I have ever loved anyone else in all my life.”

Plante’s Worlds Apart, the very title an echo of Spender’s World Within World, is in nearly all respects a satisfying, enriching memoir. We feel close to its narrator, who admits his faults and portrays those close to him with both sympathy and a cold observer’s eye. Yet while much of the narrative has the feel of immediate lived experience, based as it is on Plante’s diaries, Plante has removed chronological signposts—chapters are titled by where things take place (e.g., New York, London, Providence, Paris), not when they occurred. This timelessness has its particular beauty—an enduring sense of life lived in time out of time—yet it also gives the narrative a certain shapeless quality.

This absence of historical context also deflects issues about which Plante is either uncomfortable or not interested. There are no overt politics in the book (despite Nikos being a professed Communist), and the catastrophe of AIDS is so gingerly introduced that one would have no sense that the gay community was under medical, social, and political siege. Plante’s distance from the gay community is sometimes addressed, yet the gay people who inhabit his circle are mainly there because of their membership in that milieu. Once in a while, he drops in on the gay subculture with a friend, such as a trip to a gay bathhouse. But he goes as an observer, like a socialite slumming at a party in an ethnic ghetto. So, don’t go to Worlds Apart looking for gay history. Go there for a trenchant account of a sensitive, reflective transatlantic American author who in all senses lives between worlds—alas, standing apart from and outside of them, as he never quite roots himself.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph and a frequent contributor to these pages.