AFTER A BRIEF HIATUS, here resumes my annual roundup of some of the films I saw at the Provincetown International Film Festival (PIFF) in June. While not an LGBT festival, there are always plenty of suitable entries for this magazine. Here are four.

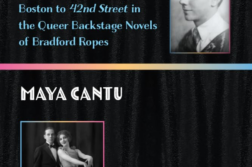

HIGH TIDE

HIGH TIDE

Directed by Marco Calvani

L. D. Entertainment

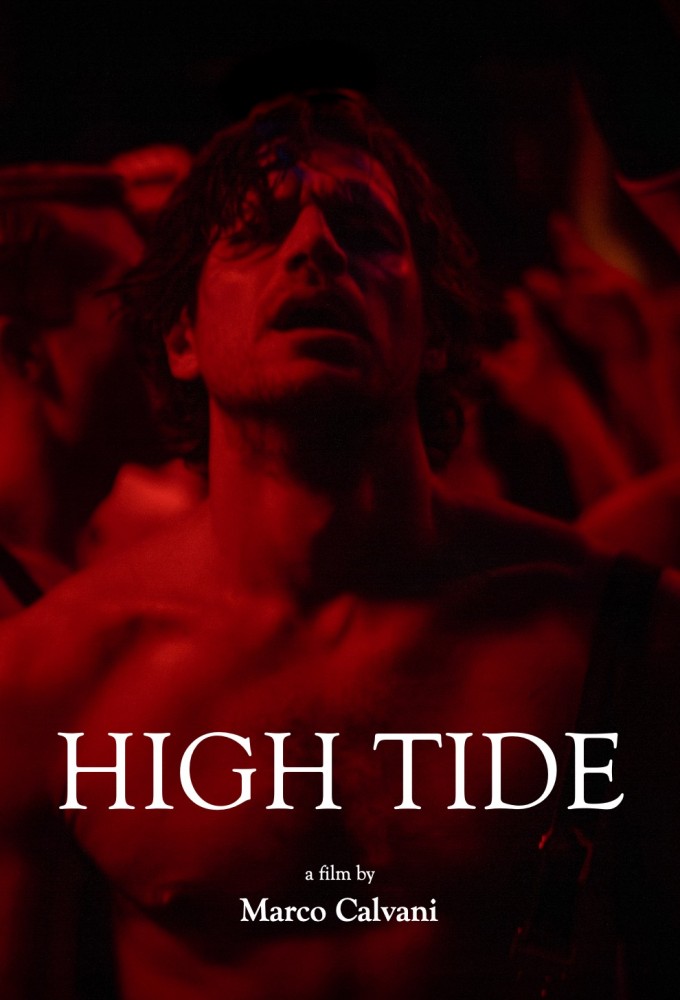

SEBASTIAN

SEBASTIAN

Directed by Mikko Mäkelä

Kino Lorber

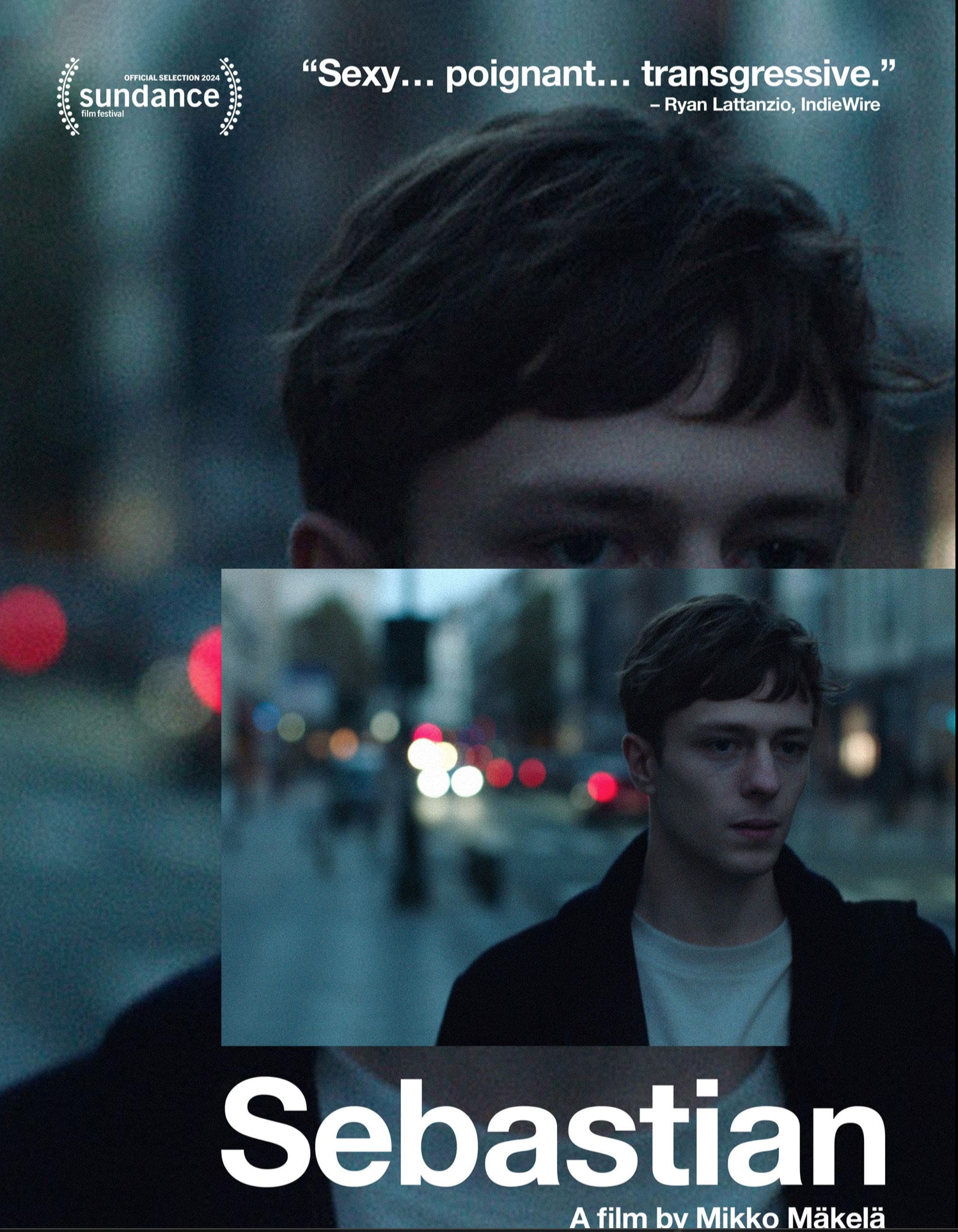

MAD ABOUT THE BOY

MAD ABOUT THE BOY

The Noël Coward Story

Directed by Barnaby Thompson

Altitude Films

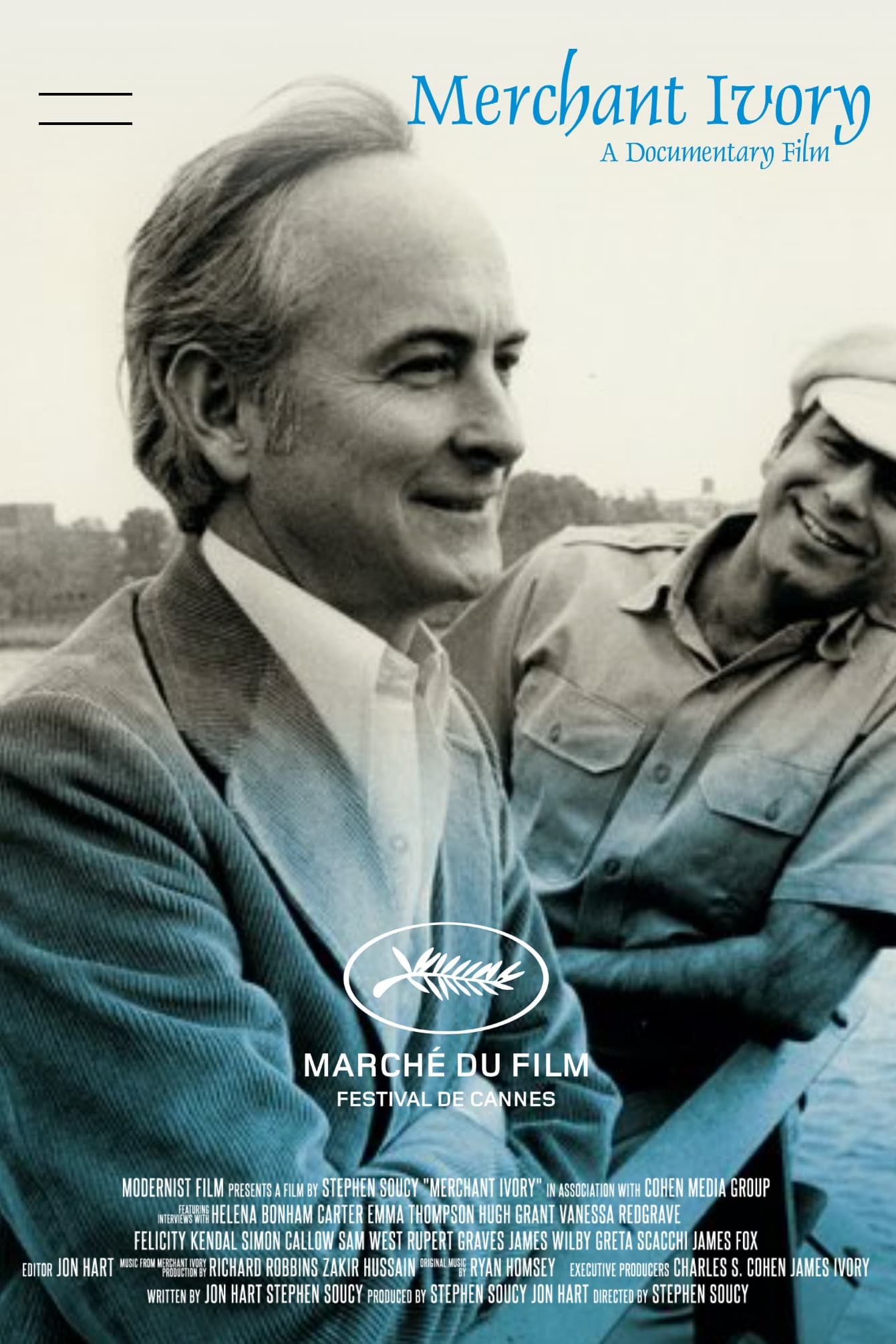

MERCHANT IVORY

MERCHANT IVORY

Directed by Stephen Soucy

Modernist Film

Filmed in Provincetown, High Tide evoked cries of recognition from the PIFF audience, which was primed to love this boy-meets-boy, boy-loses-boy romance. Nor is this the first time a film set in P’town has been screened at the festival (a “meta” moment?). That Provincetown is location bait for filmmakers is not hard to explain. There are those lingering sunsets over the water and the quaintness of Commercial Street, but there’s also an intensity that makes for high drama, or comedy. Start with the high concentration of LGBT people in a small area and add one crucial ingredient: the clock is ticking. Almost everyone you meet is there for a limited stay, whether a weekend or a week or even the season, which is all too short. A relationship can move through the entire arc from meeting to falling in love to saying goodbye in just the allotted time—or at least that’s how it works in the romcoms. Real life, of course, is never so simple. As their time winds down, decisions will have to be made. Where do we go from here?

In High Tide, the meeting of the two principals doesn’t occur until we’ve established that Lourenço, an undocumented Brazilian immigrant, is a young man living on the razor’s edge, getting by on odd jobs at the whim of his erratic bosses. We learn that his former boyfriend, who was also his U.S. sponsor, recently walked out, leaving him with a visa that’s set to expire. The taciturn Lourenço spends his free time alone on the beach, but the outgoing Maurice, who’s there with friends, calls out as he passes by and insists on talking. They make a date and it goes well; they spend the night together; they seem to be falling in love. But the clock is ticking—on the visa, on Maurice’s time in town (he works as a nurse in New York City). The film allows us, as it must, to hope that all the obstacles to their staying together can somehow be overcome.

One thing the two men share is a sense of victimhood—Maurice as a Black gay man, Lourenço as an exploited immigrant. And yet, their connection remains a fragile one; a single incident could throw everything into jeopardy. When it comes, it involves a simple misunderstanding, and here is where an ongoing source of frustration with this film rises to the fore. Lourenço is one of those brooding, silent types whose unwillingness to explain himself is undoubtedly part of his “rizz.” But sometimes this reticence means leaving an awful lot to chance.

Sebastian is a film of dualities. The title refers to the assumed identity of Max, a successful short story writer who’s trying to write a novel and works as a hustler (okay, sex worker) to get material for his fiction. After each encounter, he quickly writes down exactly what was said and done—Sebastian’s latest escapade for his thirsty readers. But Max also has a regular gig as a freelance writer for a magazine—the kind of job that comes with deadlines and staff meetings, which can really get in the way when a client is demanding a booty call.

So Max aka Sebastian is a man leading two lives, which interpenetrate in complicated ways. As a writer, Max wins prizes and critical acclaim, but no one suspects that “Sebastian” is the author himself. His old Mum doesn’t know quite what to think. She couldn’t be prouder when Max pops up on the telly for an interview, but then there’s the matter of what he actually writes about. Sebastian, too, has trouble staying in character. After every sexual encounter, he turns back into Max and sneaks off with his laptop to write it all down. When one of his clients discovers what Max has written about him, he flies into a violent rage.

The counterpart to this tyrannical client is an educated gentleman who sees through the Sebastian routine and recognizes Max as an intelligent young man who’s able to talk about the books he’s reading or has read. The Manichean contrast between these two clients—one a savior, the other a destroyer—sets the stage for the film’s exciting conclusion. It won’t be a battle between good and evil so much as a struggle to end the dualism and learn to live, and write, as a whole person: as oneself.

Throughout his life, which covered the first three-quarters of the 20th century, Noël Coward did everything in his power to conceal his homosexuality from his adoring public, and for the most part he succeeded. Yet to watch his public performances or to read his arch dialog and cheeky lyrics,

surely no one was shocked when the truth came out. If ever there were a case for a “gay sensibility” independent of one’s preferences in bed, Coward would seem to be its poster boy. His plays, mostly comedies in the tradition of Oscar Wilde, are long on style and repartee and short on message or “deeper meaning.” The wonder is that his public gave him a free pass; for a time he was even seen as a heterosexual heartthrob (but so was Liberace!).

Mad About the Boy—the title refers to a song in the 1939 musical Set to Music and almost seems too gay to describe “the Noël Coward story”—takes us through his long career with scenes from his many live appearances (both as an actor and as a stand-up performer), clips from interviews on the telly (especially one with David Frost in 1968), and fragments from his diaries as read by Rupert Everett. Alan Cumming narrates the film with personal reflections on “the Master.” While Brits of a certain age may find much of this to be old hat, the film provides a lively, at times a gushing, introduction to Coward’s extraordinary range of talents. A number of his fifty plays are still performed today (Blithe Spirit, Private Lives, et al.), and some of his 500 songs can still be heard.

As the presence of Alan Cumming might suggest, Mad About the Boy doesn’t hold back on Coward’s gayness and treats his double life as a leitmotif. In his diaries, he made no attempt to conceal his homosexuality and, unlike many a closeted gay man of his age, showed no sign of guilt or remorse. There’s even some expressly gay material in his œuvre, notably a 1966 play titled A Song of Twilight, which featured a homosexual character. But who needs gay characters when the whole project was in many ways an exercise in high camp?

One can think of a few artistic collaborators who were also LGBT partners in real life: Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears; Merce Cunningham and John Cage; the editor and publisher of this magazine (!). But never has there been a collaboration as long-lasting or productive as that of Ismail Merchant and James Ivory, the producer and director of such great films as A Passage to India, Howards End, A Room with a View, and The Remains of the Day, many adapted from novels by E. M. Forster and Henry James, featuring such marquee actors as Anthony Hopkins, Vanessa Redgrave, Emma Thompson, Hugh Grant, Simon Callow, and Maggie Smith. To tell their story from soup to nuts, Stephen Soucy’s new documentary, Merchant Ivory, moves at a somewhat breathtaking pace, incorporating interviews with dozens of the stars and a slew of clips from their major films.

Merchant Ivory films are known for their brilliant production values and gemlike surfaces, a level of perfection that belies the often “chaotic” scene behind the scenes. It was Ismail Merchant who both created and managed the chaos through sheer force of will and personal charisma, doing whatever was required to keep the machinery running, whether coaxing emergency funds from investors or cooking a memorable Indian repast to appease a restive cast and crew. Ivory, on the other hand, who’s still alive and was interviewed by Soucy, is described as understated and unflappable—an asset when dealing with the volatile Ismail. We learn that Ivory was the kind of director who gave his actors free rein to create their characters and enact their scenes without a lot of intervention. The secret was in the casting, for which Ivory had such a knack that he needed only to release the actors onto a set and allow the magic to happen.

While a wide range of material came in for adaptation by Ivory and writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, the attraction to James and Forster is noteworthy. Both were gay men who had to tread carefully in their professional and personal lives. Recent critics have found revealing subtexts in their fiction, but it was Forster who wrote an explicitly gay novel, Maurice, which was completed in 1914 but suppressed until his death in 1970. Merchant Ivory turned it into a film starring Hugh Grant and James Wilby in 1987. Soucy stresses the boldness of this release at the height of the AIDS epidemic. It could have ruined the franchise but was so damn good that both the critics and the box office gave it two thumbs up. Forster had been determined to give Maurice a happy ending, and the film version did not deviate from this plan—a novelty for a gay film at the time.