Henry James and Queer Filiation: Hardened

Henry James and Queer Filiation: Hardened

Bachelors of the Edwardian Era

by Michael Anesko

Palgrave/MacMillan. 110 pages, $69.99

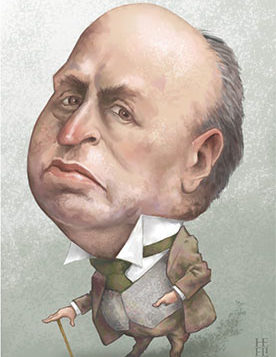

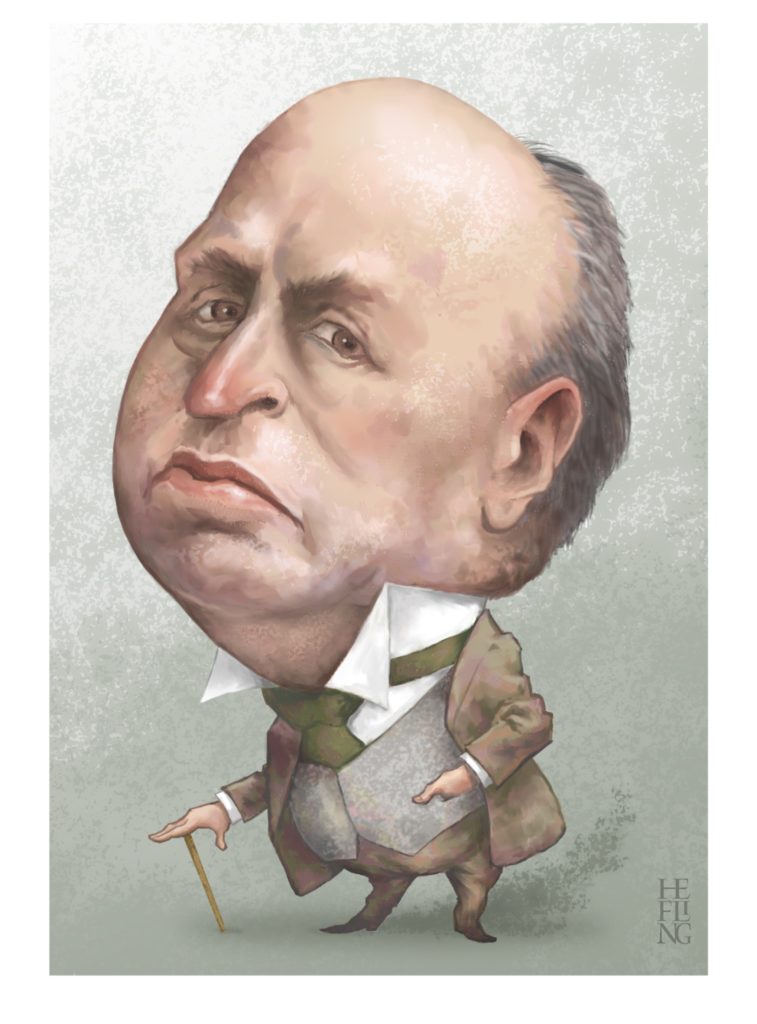

HENRY JAMES and Queer Filiationis sort of a sequel to Penn State professor Michael Anes-ko’s 2012 book, Monopolizing the Master, which is an account of how Henry James’ family tried to bowdlerize the Master’s letters after he died so that no one would think he might be homosexual.

In this new book, the fear that James might be outed centers on a less likely object: the chiseled stone inscription memorializing him in Chelsea Old Church in London. The inscription reads: “In memory of henry james: o:m./ novelist/ born in new york 1843: died in/ chelsea 1916: lover & interpreter of the fine amenities/ of brave decisions & generous/ loyalties: a resident of this/ parish who renounced a/ cherished citizenship to give/ his allegiance to england in/ the 1st year of the great war.”

The words on the inscription were composed by an American architect named John Borie, who offered his services to Mrs. William James, Henry’s sister-in-law, who had gone over to England to take care of Henry after he had a stroke, in fulfillment of a promise she’d made to her husband William before he died a few years earlier. Borie was not only an expatriate Anglophile like James but, unbeknownst to the James family, a homosexual happily living with a society pianist and voice coach named Victor Beigel. Still, one line in the inscription—”lover and interpreter of fine amenities/ of brave decisions & generous loyalties”—led Henry’s nephew Harry to worry that it might be vulnerable to perverse interpretation. Indeed, given the rather abstract nouns that echo the later style of the Master, one wonders what the phrase does mean—amenities of what kind, brave decisions to do what, and loyalties to whom?

Anesko doesn’t speculate. He uses Borie to begin a long chain of connections that lead ultimately to Henry James himself. It includes Thomas Eakins, who painted Borie; Robert Allerton, a Midwestern millionaire for whom Borie designed an enormous country house called The Farms in the middle of rural Illinois; Victor Beigel, the voice coach and pianist who became Borie’s life companion, and other “hardened bachelors” such as John Singer Sargent and the composer Percy Grainger. Not included, except in passing for some reason, is the perfect exemplar of the type, a half-English, half-American writer named Howard Sturgis, at whose house, Queen’s Acre (nicknamed by its familiars Qu’acre), many of these men gathered. Indeed, it’s not until Chapter 12 that James himself comes onstage, and we return to the drama of the book—which is basically the same as Monopolizing the Master: the family’s determination to manage James’ reputation after he died, especially in light of the letters James wrote to the sculptor Hendrik Anderson, the writer Percy Lubbock, and other young men in whose admiration James basked toward the end of his life—letters with such effusive salutations and sign-offs that Harry feared (with justice) that they might imply that his famous uncle was not so very different from Oscar Wilde, whose trial had occurred only a decade earlier.

John Singer Sargent, who gets a chapter of his own, lived across Tite Street from Oscar Wilde, where he liked to play the piano in his studio with the composers Percy Grainger, Léon Dellafosse, and Gabriel Fauré. If Harry James was afraid that his famous uncle might be exposed as a nance, what would he have made of the musical salons arranged by Sargent, who was called by one critic James’ “mirror image”? According to a fellow painter, Jacques-Émile Blanche (whose portrait of Proust is often reproduced), Sargent’s sexual exploits “were notorious in Paris, and in Venice positively scandalous. He was a frenzied bugger.” Nothing has ever been discovered to confirm this, but when Sargent was still living in Paris, he wrote a letter to Henry James introducing three French friends about to visit London; one of them was Robert de Montesquiou, the inspiration for Proust’s great homosexual character Baron de Charlus. In other words, in those days it was a very small world, of which the New England branch of the James family had no experience. It was a question—as it is in so many of James’ novels—of American innocence versus European sophistication.

John Singer Sargent, who gets a chapter of his own, lived across Tite Street from Oscar Wilde, where he liked to play the piano in his studio with the composers Percy Grainger, Léon Dellafosse, and Gabriel Fauré. If Harry James was afraid that his famous uncle might be exposed as a nance, what would he have made of the musical salons arranged by Sargent, who was called by one critic James’ “mirror image”? According to a fellow painter, Jacques-Émile Blanche (whose portrait of Proust is often reproduced), Sargent’s sexual exploits “were notorious in Paris, and in Venice positively scandalous. He was a frenzied bugger.” Nothing has ever been discovered to confirm this, but when Sargent was still living in Paris, he wrote a letter to Henry James introducing three French friends about to visit London; one of them was Robert de Montesquiou, the inspiration for Proust’s great homosexual character Baron de Charlus. In other words, in those days it was a very small world, of which the New England branch of the James family had no experience. It was a question—as it is in so many of James’ novels—of American innocence versus European sophistication.

This is a book in which one must read between the lines, and sometimes under the lines (when a sentence has been scratched out in a letter), a book of small but delicious pleasures, many of which can be found in the footnotes, which take almost as much space as the short chapters themselves. It’s a picture of a time and place and social set whose interest lies primarily in minor characters, even if the reason we’re reading about them is their relationship, however peripheral, to the James family.

Harry James was on pins and needles over the disposition of his uncle’s literary effects because of what, Anesko writes, “Jacques Derrida has diagnosed as ‘archive fever’: a compulsion to record and preserve shadowed by a competing desire ‘to burn the archive and to incite amnesia.’ Uncle Henry’s notorious bonfires of his incoming correspondence were just the beginning. A similar impulse seems to have resided in his family’s conservative temper, the evidence of which is everywhere.”

To his credit, Harry wrote to his mother that if Percy Lubbock’s editing of the letters “was not faultless … no one else’s would have been faultless either. Nothingwould have been so wrong and so contrary to all Uncle Henry’s beliefs and literary instincts as for you or me or any member of the family to have stood over Lubbock’s elbow, or for any of us to set out now to patch and ‘remedy it.’” But, Anesko continues: “The Jameses may not have stood over Lubbock’s elbow, but they certainly went over his proof sheets with watchful eyes and, previously, had carefully edited the typescript copies of letters sent to him from America to ensure that he would not even see anything they deemed personally compromising.”

To be fair, this desire to maintain a façade ran in the family. In Monopolizing the Master, we learn that Harry had to stop Uncle Henry from revising his own brother’s letters after William James died—though it’s not clear whether Henry did that for reasons of style or privacy. But it’s part of a pattern on Henry’s part. Years before his brother’s death, Henry had rushed to Venice to make sure that no embarrassing correspondence might have survived the apparent suicide of his friend Constance Fenimore Woolson, a woman whose amorous potential Henry ignored much the way Sargent ignored that of Charlotte Burkhardt, the woman everyone at one point thought he was going to marry. This is not simply a case of hardened bachelors; Sargent and James seem to have been hard-hearted bachelors as well.

Anesko’s book starts with a nod to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, but there’s no jargon in his book or the dreaded Queer Theory, though the word “queer” is used often to describe these people. And why not? About the composer Percy Grainger, “whose adrenalin-fueled performances at the keyboard were the public counterpart to the ferocious acts of auto-erotic sado-masochism that consumed him in private,” we learn in a footnote: “Whenever he went on tour he took a selection of several dozen whips with him,” and he laundered his own shirts to conceal the blood-stained evidence of his self-abuse. Even Allerton had his stable at The Farms repurposed to hold the large collection of costumes he wanted to have available for his guests so they could “discard societal conventions and become whoever, whatever, their fantasies could conjure”—“kimonos, cloaks, togas, hats and headdresses, shoes and sandals, as well as costume jewelry and other accessories.” (Sounds like drag to me.)

Anesko’s book is illustrated with portraits of some of these young men; they haunt the reader as much as anything in the text. Several of them were artists themselves. The most interesting is probably the youngest nephew of Henry James, the dyslexic, handsome, fair-haired athlete and portrait painter Alexander Robertson James, the “black sheep” of the family who disappointed his father William by not getting into Harvard, and fled his social class by becoming a painter who lived in rural New Hampshire among the farmers and workingmen who were the subjects of some of his portraits. Alexander went to art school with a man named Frederick Demmler. Lucien Price, the Harvard-educated art critic for The Boston Evening Transcript, spoke of the close friendship between Alexander and Demmler in the eulogy that Price wrote for his lover after Demmler was killed in World War I: “The two young painters proceeded to form an offensive and a defensive alliance. Where one was, there was the other also … it was good to see the pair together: two thoroughbreds. Both athletes, both artists, one dark, the other fair, both about the same height and build.” Of Demmler himself:

There had been two years in Cornell before he came to Boston. He had rowed in his class eight on Lake Cayuga. Hence that physical self-respect which betokens the young man accustomed unconcernedly to strip in a college boathouse or gymnasium. But to eyes grown impatient with the college athlete’s all-too customary intellectual torpor and social complacency it was a holiday to find this well-made body, tall, broad in the shoulder, narrow at hips, lean and muscular, housing also the brain of the thinker and the spirit of the pioneer.

One could scarcely find a more homoerotic text; Demmler sounds, in Price’s evocation, like another athlete-scholar who sprang from the Harvard boathouse—Oliver Alden, the fictional hero created by George Santayana (colleague of William James, cousin of Howard Sturgis) in his novel The Last Puritan. Henry James saw the young man differently. Demmler, while handsome and intelligent, was apparently not a big talker, which made him a debit at the dinner table. When Alexander arrived in London with his friend, James found the beautiful athlete “a dreadful impossibility for any social use whatever.” To introduce him among James’ circle of acquaintances “would be anguish for Alec & great discomfort for everyone else—like having the newspaper boy to dine.” In other words, it wasn’t enough to be good-looking: one had to be conversant with “the fine amenities”—a small glimpse of the, shall we say, hardened snobbery that characterized James’ circle of hardened bachelors.

This web of musicales, teas, gossip, and badinage among mostly male gatherings at country houses like Qu’acre (to which Edith Wharton drove Henry in her brand new motorcar) is one that the modern gay reader will easily recognize. Henry’s niece Peggy, however, found herself baffled by the scene during her visit with her uncle. In James’ novel The Ambassadors, a New England family sends an emissary to Paris to persuade their bohemian son to come home; but the emissary makes discoveries about European life that make him realize he has wasted his life in the United States. Peggy was a product of Cambridge, Massachusetts—the household of her father, the philosopher Williams James—so it’s not surprising that we get, in a letter to her mother, this report of the world in which Uncle Henry was sure Frederick Demmler would not fit:

I miss any of Dad’s quality in Uncle Henry, especially any spiritual or speculative turn. Speculative about people, yes, but of any abstract occupations of mind I can see no glimmer. We talk about people until I am sickened of the subject. … Of course it is amusing, most of it, and it is fun to hear Uncle Henry talk with others, of people where his range does not have necessarily to be so limited, but it all seems to me very shallow. For the first time Uncle Henry seems to me to be a thoroughly unreal person. All that he says, and his manner of saying it is pirouetting and prancing and beating the air, very charmingly, but still once in a while you crave a strong simple note. And yet strong it certainly is too. I don’t know. I give up—it is all too strange and wonderful for me to be able to put into words. He said himself the other day, “I hate the American simplicity. I glory in the piling up of complications of every sort. If I could pronounce the name James in any different and more elaborate way I should be in favour of doing it.”

As in The Ambassadors, so in real life: the New Englanders who came over to London to take care of Henry had no idea that the family of friends who wanted to help them in memorializing and editing their famous relative’s letters were themselves something Cambridge, Massachusetts, could not imagine. John Borie, the designer of the inscription in Chelsea Old Church, was partnered with another man. Percy Lubbock was one of the young men to whom James wrote the effusive letters toward the end of his life that worried his nephew Harry (and which were published years later in a volume called Dearly Beloved Friends). Theodora Bosanquet, the devoted typist to whom James dictated his last great novels, was shunned by the family when she offered to help with her employer’s papers, because even they realized she was a lesbian. (And, in the department of You Can’t Make This Stuff Up, Harry James’ first wife, Olivia Cushing, would turn out to be a lesbian as well.)

Although Anesko’s book is about a network of “bachelor couples” and their relationship with the James family, the irony is that neither James nor Sargent ever lived with a male partner. James famously confessed that he wrote out of his own “essential loneliness.” Sargent kept a portrait of a fellow painter, an aristocratic young man he was probably in love with, in his dining room in Chelsea all his life, but of Sargent himself a contemporary critic said: “He has met almost everybody in his day, but few people have really known him. Who has ever heard a Sargent story, and who has not heard scores of Whistler stories?” One reason for the lack of a sexual smoking gun in both men’s lives may simply be that they were married to their careers. Sargent’s sister said he “worked like a dog” from morning to night, and James never stopped writing. Another is that both Sargent and James clearly valued privacy. James thought privacy essential to civilization itself. There are sentences in his later novels that one has to read three or four times without ever quite understanding what the central metaphor is referring to, as if James were wrapping himself in a prose style so convoluted it amounted to a protective screen.

In the preface, Anesko says that “closeted secrecy” was almost a necessity for Edwardian homosexuals living in the shadow of the Oscar Wilde trial, that their domestic partnerships and quiet social lives were “a visible rebuke to the reductive stereotypes of homosexuality that circulated and were reinforced in the culture of the period.” But one senses that these were love matches as well. Victor Beigel, devastated by the death of John Borie, was buried beside him five years after Borie died, Howard Sturgis was so closely attended by The Babe while he was dying that he apologized for taking so long, reminding his companion that “a watched pot never boils” (surely one of the funniest deathbed remarks ever). Robert Allerton adopted the young man he met at a fraternity Father-Son banquet as his son and left him his entire estate. And there could scarcely be any text more loving than the eulogy Lucien Price wrote for Frederick Demmler. Which leaves the two exceptions. Sargent died in London, in bed, next to the book he’d been reading. James was seen out by Alice and Peggy James and so many other women that he confessed he was “perplexed by the absence of the male element in my entourage.”