ON SEPTEMBER 26, 1957, West Side Story premiered on Broadway at the Winter Garden Theater and was instantly hailed as a milestone in the history of American musical theater. Arthur Laurents’ script presented an updated version of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Julietin which the star-crossed lovers were placed in Manhattan in the 1950s. Shakespeare’s Romeo became Tony, the son of Polish immigrants, and Juliet became Maria, a teenager who had recently emigrated from Puerto Rico. The feuding Capulets and Montagues had their counterparts in the rival gangs known as the Jets and the Sharks.

Infused throughout West Side Story is a gay sensibility that’s expressed subtextually in the relationship between the hero Tony and Riff, the leader of the Jets, and choreographically through the homoeroticism of the all-male dance sequences. Equally bold is the inclusion of the character named Anybodys, a teenage girl who identifies as a male and longs to be accepted as a full member of the Jets. Anybodys is Broadway’s first transgender youth.

Along with Arthur Laurents, composer Leonard Bernstein, director-choreographer Jerome Robbins, and lyricist Stephen Sondheim were all in various stages of coming to terms with their homosexuality in the oppressive atmosphere of 1950s America. With the exception of Sondheim, the creators of West Side Story had narrowly escaped professional ruin during the anti-gay and anti-Communist witch hunts of the McCarthy era. By 1957, the persecutions were essentially over, the far Right was in retreat, and West Side Story afforded four gay men an opportunity to create a work of art that challenged prejudice and affirmed the power of love in defiance of social norms.

Reviewers praised West Side Story for its sociological boldness and for changing the face of the American musical theater, but they did not comment, at least publicly, on the gay subtext of character relationships or the homoeroticism of the dancing. Sixty years after its premiere in New York City, the musical deserves to be revisited, including the gay elements that tiptoe through the story along with an overall gay sensibility that shows up in the story, the lyrics, and the dancing. The sexual proclivities of the four collaborators, far from being irrelevant, served as a rich source of creative inspiration.

Jerome Robbins: Origins of the Musical

Robbins is credited by his collaborators with the original concept for the musical. In 1948, he enrolled in the famous Actors Studio, where “The Method” was taught. One of his peers was actor Montgomery Clift, who was playing the part of Romeo and sought Robbins’ assistance in making the role more relatable to audiences. Clift and Robbins were lovers for several years. His idea for a modern-day Romeo and Julietemerged at this time and was thus intertwined in Robbins’ psyche with a homosexual relationship.

The result was a scenario about two young people in love, one Jewish and one Catholic, which would take place during the celebrations of Passover and Easter. The play would be called East Side Story. In 1949, Robbins approached Arthur Laurents and Leonard Bernstein about creating a musical based on this concept. From its inception, the play was connected with intolerance and social barriers, subjects that resonated with the three men, all of whom were Jewish as well as gay (or at least struggling with being gay).

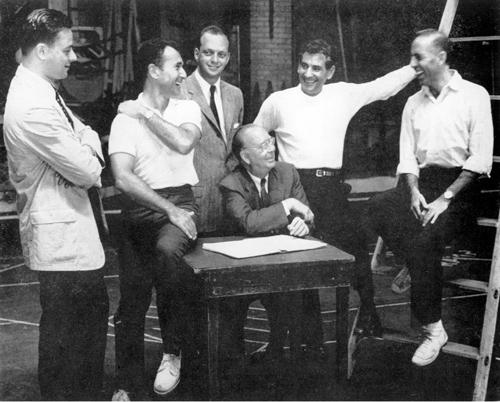

In 1955, after a long hiatus, the project came back to life, but the story was radically recast to focus on racial rather than religious prejudice. Shakespeare’s senseless feud between the Capulets and the Montagues was transmuted into gang rivalry underpinned by racism. Jerome Robbins agreed to be director as well as choreographer, and when Laurents recruited the virtually unknown 25-year-old songwriter Stephen Sondheim to be co-lyricist with Bernstein, the creative team was complete.

Few figures in the history of Broadway musicals have engendered more controversy than Jerome Robbins. Tormented by inner conflicts related to his homosexuality, he routinely abused and humiliated the large cast of singers, actors, and dancers. At times he even berated his three collaborators in front of the production team.

Robbins had a tumultuous life history. In 1943 he joined the Communist Party, attracted by the party’s promotion of minority and workers’ rights, apparently unaware of the party’s hostility towards homosexuality. His left-wing politics made him a target for reactionary forces in the McCarthy era. Ed Sullivan, a columnist for the New York Daily News, threatened to expose his affairs with men if Robbins did not cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The outcome damned Robbins eternally in the eyes of many in the entertainment industry: On May 5, 1953, Robbins testified voluntarily before the House Un-American Activities Committee, giving the names of colleagues he said were communists. That Bernstein and Laurents were willing to give Robbins a second chance by working with him on West Side Story testifies to the deep bond among the three men. Robbins himself may have seen West Side Story, with its progressive social message, as a chance to redeem himself after his act of betrayal.

As West Side Story’s choreographer, Robbins came into the fullness of his genius and emerged as the most innovative American choreographer of his generation. The play’s first scene relies entirely on dance and music to convey the history of the Jets, a gang of white youths. In this all-male “Prologue,” Robbins subverts macho stereotypes by having the street-tough, violent young men engage in graceful, balletic movements. The sensual dancing establishes the bonds of love among the gang members and radiates a distinctly homoerotic sexual energy.

While Robbins’ perfectionism yielded memorable results on stage, the pressures that mounted in the months before the premiere also brought out the worst in him. While tyrannical with the company as a whole, he singled out the male lead, Larry Kert, for particular cruelty. Cast as Tony, Maria’s lover, Larry Kert was a rarity in the 1950s: an openly gay actor. Robbins clearly knew Kert was gay when the role was cast, but at some point before the premiere his attitude towards his leading actor changed. One day during rehearsal of the rumble scene in which Bernardo kills Riff and then Tony retaliates by killing Bernardo, Robbins became frustrated with Kert’s movements. Arthur Laurents recounts the painful scene in his memoir: “’Faggot!’ Jerry shouted at him over and over. ‘Do you have to walk like a faggot? Can’t you move like a man, you faggot!’”

Depressed by his abusive director, Larry Kert nevertheless went on to triumph on the Broadway stage as Tony. His full-bodied, lyric tenor voice is preserved on the original cast album. Kert’s characterization of Tony as a sensitive dreamer, weary of macho violence, has set the standard for interpretations of the role in the many revivals since 1957. The show ran for 732 performances on Broadway and was viewed by critics as Robbins’ particular triumph. At the 1958 Tony Awards, Robbins was the only one of the four to be honored with a Tony Award for his work on the musical, winning in the category of choreography. When it came to the award for Best Musical, West Side Story lost to a feel-good show about marching bands and wholesome Americana called The Music Man.

Arthur Laurents’ Social Realism

Updating Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the most famous love story in the English language, was a creative challenge that might have defeated a playwright with less talent than Arthur Laurents. Born in 1918, making him the same age as Robbins and Bernstein, by the 1950s Laurents was one of America’s most renowned playwrights and screenwriters.

His first play, Home of the Brave, premiered in New York in 1945 and won critical acclaim. The autobiographical hero, Coney, is a Jewish soldier who’s embittered by the anti-Semitism around him. In Original StoryBy, Laurents’ memoir, he characterizes the relationship between Coney and his buddy Finch as psychologically homosexual. Both Home of the Braveand West Side Story were informed by Laurents’ experience of prejudice as a gay man and a Jew. He writes: “My first play and my first musical center on prejudice. Possibly a coincidence, probably not, but no matter: a decade after the play, I still had more than enough anger to fire the musical.”

In 1955, when East Side Storybecame West Side Story and Laurents began writing in earnest, the author was grappling with prejudice on a daily basis due to his decision to move in with his lover, Tom Hatcher, a handsome, blond actor whom he had met in Hollywood. Living as a male couple in the 1950s meant the daily risk of harassment and professional ruin. Thus forbidden love was very much on Laurents’ mind as he was writing West Side Story. The relationship between Riff, the leader of the Jets, and his best friend Tony is central to the plot. Riff has lived with Tony and his family for four years, and while Tony is drifting away from the Jets, Riff is determined to hold onto him.

The erotic nature of the bond between Riff and Tony is conveyed in Act I, scene II in an exchange of internally rhyming phrases that is a pattern in their conversation. In pleading with Tony to come to the dance and maintain his connection with the Jets, Riff invokes their history together when he says: “Because it’s me asking. Womb to tomb!” “Sperm to worm!,” replies Tony, sexing things up. Running through the relationship between Riff and Tony is a subtext that’s romantic and sexual, reminiscent of Coney and Finch in Home of the Brave. Viewing Tony as a bisexual man, in love with both Riff and Maria, intensifies the dramatic tension in the play and augments the theme of love that defies social norms.

The tragic turning point in West Side Story is the rumble scene, Act I, scene 4, in which Tony’s attempt to stop the fighting between the two gangs has fatal consequences. Riff is killed by Bernardo and Tony retaliates by stabbing Bernardo, Maria’s brother. His killing of Bernardo is a crime of passion, a response to losing the man he has loved for so long. Tony is a tragic victim, and the real culprit is a culture defined by racism, homophobia, and macho violence.

The atmosphere of sexual rebellion is reinforced by Laurents’ invention of a character named Anybodys, who is not based on any character in Romeo and Juliet. Anybodys is a teenage girl who dresses in the male uniform of the Jets, talks tough, fights effectively, and longs to join the gang. Laurents’ sympathetic portrait of Anybodys as a transgender youth is a Broadway milestone. As the play progresses, Anybodys grows in stature. She saves Tony from being arrested after the rumble, and later that night she bravely infiltrates the Sharks’ territory and learns that Chino is searching for Tony with a gun. If Anybodys were empowered by the Jets, she might have assisted Tony in his plan to leave New York with Maria, thus saving him from being murdered.

Drawing upon his own experiences as a gay, Jewish man in the 1950s, Laurents sends an emotionally resonant, socially subversive message in West Side Story. The deaths of three major characters by the end, including the hero Tony with whom Arthur Laurents so strongly identifies, is a scathing commentary on the misguided traditions that ruin lives and destroy love.

Leonard Bernstein: Composing the Dream

Of the four gay men who created West Side Story, Bernstein was a genuine celebrity of the era. For many years the conductor of the prestigious New York Philharmonic, Bernstein’s classical compositions included three symphonies, but it was ultimately his music for West Side Story that would come to be regarded as his masterpiece.

Love and sexuality were as important to Bernstein as his passion for music. He first acted on his sexual feelings for men in his youth, most likely during his years as a musical prodigy at Harvard University. In his early twenties he forged connections with luminaries in the classical music world such as Aaron Copland. He scored his first triumph in New York when he composed the music for the ballet Fancy Free(1944), which was choreographed by Jerome Robbins, with whom Bernstein may have had an affair.

Bernstein’s years in New York were a time of sexual freedom and intense creative output, with writing the music for hit musicals such as On The Townand Wonderful Town. But his growing fame and, very likely, the FBI’s knowledge of his sexuality resulted in Bernstein being blacklisted by CBS Radio and TV in 1950. The fear of being destroyed professionally may have contributed to his decision to try to counter his homosexual nature by getting married to Felicia Montealegre, an actress. Be it noted that Bernstein was the only one of the four collaborators to be married. His sexual relationships with men did not end with his marriage, however. By the mid-1950s, the truth of his sexual nature had become apparent to Felicia, as indicated in a frank letter she wrote to her husband in the early years of their married life.

Conforming to an outwardly traditional role did not diminish Bernstein’s charisma or attractiveness. At the time of West Side Story, he was in his late thirties, extroverted and ebullient, with a zest for life and a passion for political causes, including the new nation of Israel. Photographs reveal a strikingly handsome man with a shock of hair over his forehead, blending the image of the wild maestro with the debonair charm of Cary Grant. He once described the relationship between himself as a conductor and the members of his orchestra as follows: “One rides on something like waves of love which are dictated by the composer. It is sort of sexual.”

Bernstein’s musical score for West Side Story is considered by many musicologists to be the finest ever composed for a Broadway musical. The sound is youthful, modern, jazzy, and erotic, as exemplified by the “Prologue,” the all-male opening that introduces the Jets and the Sharks. The finger-snapping that punctuates the dance, the use of musical dissonance, and the brassy explosions of sound create a sexually charged musical texture which, accompanying Robbins’ sensual choreography for the male dancers, conveys a homoerotic feeling.

In composing the score, Bernstein became very close to the young Stephen Sondheim, his co-lyricist. When the show opened in Washington, the reviews completely ignored Sondheim, and he became despondent. In an extraordinarily magnanimous gesture, Bernstein offered to remove his own name as co-lyricist, giving Sondheim the full writing credit in order to boost his career. How many of Bernstein’s lyrics survive in the musical that opened in New York is a matter of conjecture.

A song that is quintessential Bernstein for its romantic qualities may well contain lyrics he wrote for Tony and Maria after the deaths of Riff and Bernardo. The ballad is called “Somewhere” and expresses a yearning of the lovers to be free from their hostile surroundings. “There’s a place for us,/ A time and place for us./ Hold my hand and we’re halfway there./ Hold my hand and I’ll take you there./ Somewhere.” It might be supposed that Bernstein’s dream of finding “a new way of living” has personal overtones related to his longing for the freedom to express his true sexual nature. Writes Bernstein biographer Allan Shawn: “He had no personal experience of gang violence, but he certainly knew anti-Semitism and surely, like all his collaborative team, understood sexual intolerance and the risk of admitting to a love that violated social norms.”

Stephen Sondheim: Something’s Coming

A theatrical neophyte compared to his three collaborators and twelve years their junior, Stephen Sondheim was also in an early stage of understanding his homosexual identity. Since his youth, when he was mentored by Oscar Hammerstein II, who became a surrogate father to him, Sondheim had nurtured the seemingly impossible dream of having a musical produced on Broadway by the time he was thirty. Writing the lyrics for West Side Story was the break of a lifetime. The daily collaboration with three gay men whom he admired deeply must have been amazing, a hint of things to come. Tony’s opening song, “Something’s Coming,” captures this spirit of anticipation. The song is a musical soliloquy in which Tony expresses an all-consuming desire to meet someone who will change his life forever. “With a click, with a shock,/ Phone’ll jingle, door’ll knock,/ Open the latch!/ Something’s coming, don’t know when, but it’s soon—/ Catch the moon,/ One-handed catch!” The yearning is expressed in gender-neutral terms, allowing for an open interpretation of Tony’s sexuality. The “something” he awaits could be anything—something unprecedented, perhaps taboo, that might turn out to be wonderful.

Many of Sondheim’s lyrics in West Side Story are rich with sociological implications and psychological darkness. In depicting the lives and thought patterns of gang members and alienated youths, Sondheim’s lyrics are sardonic, hip, and surprisingly graphic for the late 1950s. The song “Gee, Officer Krupke” is a blistering, hilarious attack on socially defined concepts of normality. Riff and the Jets thumb their noses at a range of social authorities: the agents of the law, psychologists, social workers, and the family. An oddly suggestive passage goes like this: “Gee, Office Krupke,/ We’re down on our knees,/ ‘Cause no one wants a fella with a social disease.” The youths’ anger at the buffoonish Officer Krupke perfectly expresses the anger felt by homosexuals in the 1950s at a society that reduced them to criminals.

Sondheim’s original ending to the song was intended to shock audiences and be a Broadway first: “Gee, Officer Krupke—Fuck you!” However, the salty language was nixed by Columbia Records, the producer of the original cast album, on the grounds that obscenity laws would make it illegal to ship the album across state lines. Bernstein saved the day by coming up with the phrase “Krup you!,” which was more subtle and delighted the creative team.

The sensational success of West Side Story launched Sondheim into Broadway’s stratosphere, and doors were opened by producers and directors everywhere. Sexual fulfillment, however, did not come quite so rapidly or spectacularly, though things were moving in that direction, however slowly. It would be several more years before he had his first affair with a man.

Sondheim never again worked with Bernstein, whose kindness towards the younger man had been so crucial. But immediately following the success of West Side Story, he was again working side-by-side with Arthur Laurents and Jerome Robbins, this time on the musical Gypsy, which premiered on Broadway in 1959 and starred Ethel Merman. Once again it was Laurents, who by now had become an intimate friend, who brought Sondheim on board. Sondheim’s interest was piqued when he learned that Rose, the central character and the mother of the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, was a lesbian who had had many affairs with women in the early 1900s.

The Legacy of West Side Story

West Side Story’s status as one of the most enduring works of the American musical theatre was enhanced by the release of the film adaptation starring Natalie Wood and Richard Beymer on October 18, 1961. Co-directed by Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins, the film received reviews that were even more laudatory than those for the stage production. The movie won ten Oscars, a record for a musical, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actress for Rita Moreno, the only Hispanic actor in one of the leading roles.

Of the four gay men who were responsible for the stage play, only Jerome Robbins had any involvement with the movie, but before filming was complete the producers decided to fire Robbins. This setback did not, however, stop Robbins from showing up at the Oscars ceremony to collect his shared Best Director award along with Wise. West Side Story on stage and screen cemented Jerome Robbins’ status as a brilliant modern choreographer and made him a rich man. But fame and financial security did not enable his personal demons to subside, and he never fully accepted his gayness. He died in New York in 1998, only a few months before the opening of a London revival of West Side Story.

Arthur Laurents never received the adulation accorded to Robbins and Bernstein for their contribution to the Broadway musical, though his book reads even more brilliantly with the passage of time. West Side Story was Laurents’ first involvement in a musical, and he followed up by directing I Can Get it For You Wholesale, which starred a young actress who was in fact his discovery: Barbra Streisand. The social realism of his book for West Side Story continued to animate Laurents’ work for decades to come. He scored a professional triumph in 1983 when he directed the hit musicalLa Cage Aux Folles, which celebrates gay characters who are out, proud, and on the cutting edge of social change. Laurents’ personal life evolved over the decades, and his life partnership with Tom Hatcher became publicly known. Laurents published several frankly written memoirs in his later years and died in 2011 at age 93.

It would be an understatement to say that Stephen Sondheim achieved his dream of writing both the music and the lyrics for Broadway musicals. To mention only a few of his better-known Broadway musicals—A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Company, Sweeney Todd, A Little Night Music—there’s little doubt that West Side Story was formative, his first opportunity to write the edgy lyrics that would become his trademark. By the 1970s, former mentors such as Leonard Bernstein were participating in tributes to Sondheim, sometimes pronouncing him the greatest creative force in musical theater of the 20th century. Today Stephen Sondheim is still going strong at the age of 87, and he is open about being a gay man.

Of the four collaborators, Leonard Bernstein came to be the most closely identified with West Side Story. His score is regarded as a uniquely brilliant and complex work for the musical theater. His Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, an orchestral overture based on the stage songs, is now performed in classical concert halls along with other of Bernstein’s more formal works. Paradoxically, it was Bernstein, the only one of the four collaborators who ever married, who did the most to break the silence about homosexuality in the arts. His wife died in 1978, leaving him grief-stricken. But in the 1980s, he embarked on a new phase of his life, which included public appearances with a variety of male lovers in support of gay causes.

When Leonard Bernstein died on October 14, 1990, Jerome Robbins, Arthur Laurents, and Stephen Sondheim gathered for an intimate funeral service with Bernstein’s closest friends and family. It was the last time the four men were together.

David LaFontaine is a professor in the English Department at Massasoit Community College in Massachusetts.

Discussion5 Comments

Anyboys is a girl! it is so beyond offensive to take a character that is a tomboy and say she is really a boy. I will be sticking to the 1961 version where tomboyish girls are not being told that they are trans.

Agreed.

Agree I was a tomboy in the 1960s and 70s. I was just good at running climbing fences etc. I was better than some boys.

I could not agree with you more, Ivy! Thanks for some good points that are well taken.

Riff is bi I believe I haven’t read the whole article sorry if you already mentioned it