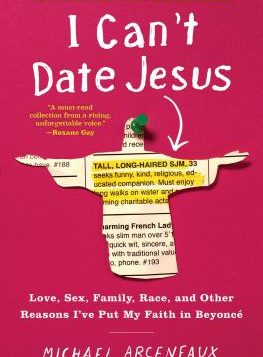

I Can’t Date Jesus: Love, Sex, Family, Race, and Other Reasons I’ve Put My Faith in Beyoncé

I Can’t Date Jesus: Love, Sex, Family, Race, and Other Reasons I’ve Put My Faith in Beyoncé

by Michael Arceneaux

Atria/37 Ink. 256 pages, $17.

MICHAEL ARCENEAUX, born in Houston to a family originally from Louisiana, is a self-described country boy. He was raised Catholic but by his twenties had stopped attending church, much to the chagrin of his devout mother. Arceneaux, who now lives in Harlem, is black and gay. Since graduating from college more than twenty years ago, he has made his living as a writer of essays that have appeared in print publications, social media, and now in his first book, in which he writes, often quite humorously, about his personal life. His take on what it means to be a gay, African-American ex-Catholic from Texas often defies expectations and forces readers to confront their comfortable but misguided assumptions on any number of topics. I Can’t Date Jesus can be both funny and unsettling.

The book’s essays constitute a disjointed autobiography. Arceneaux writes about his childhood sexual experiences, his early religious indoctrination, his love for female recording artists (particularly Beyoncé), his struggle to make a living as a writer, coming out, and dating. He frequently makes fun of himself. There are disastrous first dates where he drinks too much, his struggle to live in Los Angeles without a car, and his fear that a man he met online has infested his apartment with bedbugs. His humor, however, cuts both ways. He doesn’t hesitate to call one of the men he dates a stupid, superficial jackass. Forced to ride the bus in L.A., he complains: “On top of the bus being crammed full of people who needed to better familiarize themselves with manners and strong deodorant, it was a wonderfully shitty way to get around the city.” It is not surprising that a blog he wrote is called “The Cynical Ones.” He refuses to express sympathy he doesn’t feel, whether toward dysfunctional members of his own family or poor people riding the bus.

He’s equally uncompromising in his use of black vernacular. Words such as “nigga,” “ho,” and “bitch” appear frequently, usually in a benign if not humorous context. Confronted with homophobia in a class at Howard University, he writes that he “promptly raised my hand to shut the dumb shit the fuck down.” Here the comic effect of the language underscores the seriousness of the situation. All of the essays in I Can’t Date Jesus have profoundly serious things to say about being gay and black in America. Remembering the time Fr. Marty, an African-American priest who must have sensed that the young Michael was not likely to date girls, approached him about becoming a priest, he does comic riffs on confession and vestments. It was this encounter that prompted him to ask fundamental questions about embracing a religion that expected him not to act on his sexual desires.

The strongest essays deal with Arceneaux’ conflicted relationships with his mother and father, with the man currently occupying the White House, and with the power of “whiteness” to oppress black people. When Michael was young, his paternal uncle died of AIDS. His father’s drunken reaction, “Fuck that faggot,” caused Michael to fear both AIDS and his own burgeoning sexual impulses. Combined with his father’s abusive treatment of his mother, this experience initiated difficulties with sexual and emotional intimacy that continue to plague him. He acknowledges that his mother is the strongest person he has ever known and that she’s responsible for his drive to succeed. But the Christian doctrines that she lives by make her unable to accept that her son is gay. There is no happy ending to this story, only a declaration of “how much we love each other.”

The short essay on the 45th president is called “Sweet Potato Saddam.” The title is one of Arceneaux’ substitutes for “that jackass’s name.” In blunt terms, he calls out the undeniable racism in America that determined the outcome of the 2016 election, a racism that surprised everyone but black people. “The Pinkprint” is a powerful essay that addresses the tremendous gulf between black and white America. Arceneaux is unflinching in his comments about the real reasons for the high rate of HIV infection among black and Latino gay men and about our delusional discussions concerning sexual racism among gay men. It is a defiant essay, written by a country boy who gave up on Jesus and, with Beyoncé’s help, put his faith in himself.

Daniel A Burr, a frequent contributor, lives in Covington, KY.