In One Person

In One Person

by John Irving

Simon & Schuster. 425 pages, $28.

IT HAS BEEN a while since I read any John Irving, so I was looking forward to his latest novel, In One Person, whose themes of sexual variation and gender identity had been widely reported. Irving is an unrepentant liberal, and although it may not have changed the debate, his novel The Cider House Rules (1985) was a welcome defense of abortion rights. Irving has his detractors, of course, some of whom find him wanting compared to his literary hero, Charles Dickens. Others, who don’t like Dickens’ overly broad characters and penchant for sentimentality, will feel that Irving does not escape some of these very weaknesses.

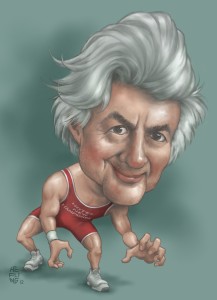

In One Person is certainly as intelligent as Irving’s earlier work, and thematically as serious. The author commented to The New York Times upon its publication: “Gay rights is a civil rights issue. … The sexual backwardness of our country has always fueled my writing—we are a sexually repressive country, a sexually punitive country.” So what’s not to like about a straight man, a former amateur wrestler and wrestling coach, who has the courage of these convictions?

The story is told by Billy Abbott, who’s at the center of a sexual saga with tragic dimensions, yet Billy’s voice as he tells the tale—and in true Irving spirit, it is an epic and picturesque tale, full of asides and jokes, literary allusions and literary argument—is less self-aware than self-consciously arch, often at odds with the adult recalling emotional deprivations and sexual confusions of his youth in the early 1960’s. Living in a small New England town, First Sister, Vermont, Billy is the son of a woman who, like Jenny Garp, has no use for the man who fathered her child. He is mysteriously out of the picture, leaving behind him the myth of a man who worked on “codes” during World War II, was a “notorious womanizer,” married Billy’s mother a year after the boy was born, and divorced her a year later.

The major plots, no one of which dominates, involve a circle of eccentric characters, from Grandpa Harry, who likes to cross-dress in the town’s amateur theatricals, to Miss Frost, the First Sister librarian whose earliest physical description—wide shoulders, large hands, and small breasts—tele-graphs that we are dealing with a woman by choice, not birth. Miss Frost will become Billy’s sexual fixation, literary mentor, and lifetime touchstone. Others populating the story include Richard Abbott, an English teacher at Favorite River Academy, the local boys prep school, where he will direct student productions of Shakespeare and marry Billy’s mother, thereby bringing Billy into the school’s fold; Elaine Hadley, Billy’s best friend and confidant; Nana Victoria, Grandpa Harry’s sniffy wife; Aunt Muriel, Billy’s moralizing aunt; and a short roster of fellow Academy students, most importantly Kittredge, the beautiful wrestler and social superior who walks around with a chip on his shoulder while assuming the airs of a sexually knowing jock lording it over his teammates and lesser mortals. While young Billy is aware of how inappropriate his crush on Miss Frost is, he is mortified that he also has a crush on Kittredge, since “it was not my imagination that every other word out of many of the older boys’ mouths was ‘homo’ or ‘fag’ or ‘queer.’” Indeed, Billy understands that these words were “the worst things you could say about another boy at the prep school.”

The major plots, no one of which dominates, involve a circle of eccentric characters, from Grandpa Harry, who likes to cross-dress in the town’s amateur theatricals, to Miss Frost, the First Sister librarian whose earliest physical description—wide shoulders, large hands, and small breasts—tele-graphs that we are dealing with a woman by choice, not birth. Miss Frost will become Billy’s sexual fixation, literary mentor, and lifetime touchstone. Others populating the story include Richard Abbott, an English teacher at Favorite River Academy, the local boys prep school, where he will direct student productions of Shakespeare and marry Billy’s mother, thereby bringing Billy into the school’s fold; Elaine Hadley, Billy’s best friend and confidant; Nana Victoria, Grandpa Harry’s sniffy wife; Aunt Muriel, Billy’s moralizing aunt; and a short roster of fellow Academy students, most importantly Kittredge, the beautiful wrestler and social superior who walks around with a chip on his shoulder while assuming the airs of a sexually knowing jock lording it over his teammates and lesser mortals. While young Billy is aware of how inappropriate his crush on Miss Frost is, he is mortified that he also has a crush on Kittredge, since “it was not my imagination that every other word out of many of the older boys’ mouths was ‘homo’ or ‘fag’ or ‘queer.’” Indeed, Billy understands that these words were “the worst things you could say about another boy at the prep school.”

The story’s early focus rests on discovering the truth about Miss Frost, and under what circumstances Billy (“William” to Miss Frost) will admit to his attraction to her. Then there is Billy’s father, William Frances Dean, a ghost figure about whom Billy’s mother has nothing kind to say, yet by her wary silence suggests some mysterious mistreatment. Kittredge, too, is enigmatic—a boy capable of petty and large cruelties who blames his beautiful mother for, well, everything, and we’ll eventually find out a dirty Kittredge family secret.

Sex and gender are the meat of the story, and there are times when this reader couldn’t help wondering if 1960’s First Sister, Vermont, and Favorite River Academy housed a kinkier group of eccentrics than live today on my block in Chelsea. Is it possible for a novel to be too queer? Reading In One Person, there were moments when I felt like Joan Cusack in In and Out, who, left at the altar by her suddenly gay fiancé, walks out into the middle of the road and cries to the heavens, “Is everybody gay?” So many characters prove to be sexually transgressive in some way that we suspect Irving of stacking the deck—especially given that the core story takes place in pre-youth revolution Vermont.

But even if we accept a high percentage of this, Billy’s maddening focus on small-breasted women (Miss Frost, Elaine, Elaine’s mother, Martha Hadley—another of Billy’s sexual obsessions), their brassieres, and his mispronunciation of “penis” and “penises” becomes a tiresome series of comic tropes. Likewise the other oddball tics, phrases, and epithets that Irving deploys, like a latter-day Dickens, to remind us of which character is which.

Some may find Irving’s antic sense of humor part of the attraction of this tale. Lavishly plotted, the story occasionally moves in flash-forwards to Europe, first for Billy’s maiden voyage with a Favorite River classmate after graduation, then to his foreign exchange experience in Vienna, where he will take up with both a budding soprano and one of his older male professors, a gay American poet of some repute; and his eventual co-habitation with Elaine (a sass-mouthed angry girl that Irving has invoked before) in New York City. At all stages, Billy’s bisexuality, he reminds us, is regarded as suspect by straight and gay friends, including sexual intimates. As a narrator, Billy assumes a wealth of “insider” knowledge about the gay world, taking us on a brief tour of gay history. Irving has certainly done his homework.

The cataclysm of AIDS touches Billy’s life in the 1980’s and into the 90’s. Here at last, Billy’s voice retreats from wise-acre humor and delves deep inside the emotional pain, the social reverberations, and the indifferent political response. Characters from Billy’s youth re-emerge after long absence from the narrative, so that young men once held near or distant in his affections are now afflicted. Despite his own wide sexual experience, a reasonable explanation is given for his avoidance of the plague.

Of those early plot mysteries that require resolution, only Miss Frost’s personal history is given ample explanation and some resonance in the narrative of Billy’s life. Billy’s mother disappears relatively early. Irving never gives her the chance to speak on her own behalf; her motives and past history remain a mystery. As for Kittredge, Irving allows him to leave the stage rather early, thereafter to be talked about and re-encountered via simulacrum.

And so we are left with Billy, whose absent father, William Francis Dean, finally re-appears at the end after our narrator has matured into a successful writer. The problem is that Billy’s father comes in too late—another sexual outlaw!—and remains a figure of too much emotional withholding to fully satisfy any reader hoping for a father-son catharsis. But Irving does have a few other plot tricks up his sleeve. Suffice it to say that William “Billy” Abbott returns to the scenes of his Vermont youth to settle in First Sister and teach at Favorite River Academy. There, at least one young student will give him the opportunity to defend the principles of sexual tolerance that Miss Frost had personified back in the day.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph, which has just been reissued by Columbia University Press.