UNRULY DESIRES

UNRULY DESIRES

American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail

by William Benemann

Independently Published

356 pages, $15.95

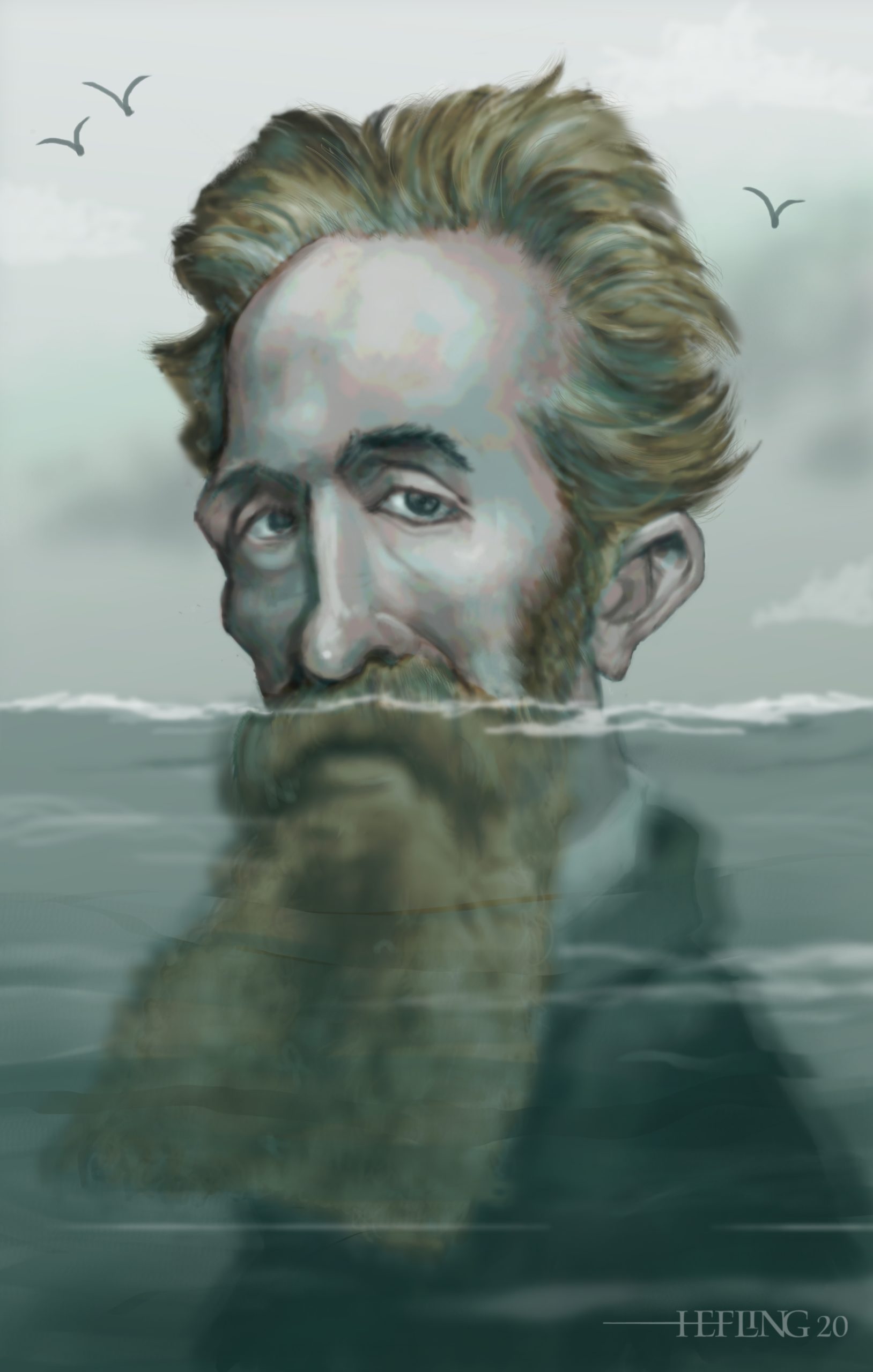

ANYONE who has read Moby- Dick will recall the scenes of Ishmael and Queequeg sharing a bed, or Ishmael giddily squeezing the hands of his fellow sailors in the sperm oil chapter, and wonder if Herman Melville was hinting at something more between Ishmael and his shipmates than mere camaraderie. An even more suggestive dynamic emerges in Melville’s Billy Budd involving the title character, Claggart, and Captain Vere, who describes Billy as “”the young fellow who seems so popular with the men—Billy, the Handsome Sailor.”

In William Benemann’s insightful study, the driving urge for Ishmael and many others to take to the sea may have been about more than depression or adventurism. It just may have been because sailing ships offered one of the few places where one can express same-sex desire.

Even in the 19th century, sailing ships were known to be places in which men could have sex with other men. Indeed, he cites one source which indicates that mutual masturbation—commonly referred to as “going chaw for chaw”—was so frequently indulged in that solitary masturbation came to be viewed as suspect. Similarly, in an institution known as “chickenship,” a younger sailor would provide sexual services to an older sailor in exchange for various favors. There are numerous examples given where an especially good-looking boy would have two or even three men on board with whom he was engaged.

One of the main arguments of Benemann’s study is that such male intimacy is not merely an accident of life at sea but instead an important draw for many who chose sailing as a profession. The author’s case for this is convincing and enlightening. He begins, for instance, by noting that the sites for naval recruitment were saloons and boarding houses for transients—precisely the venues frequented by the marginalized—and that this placement was strategic. By visiting sites frequented by society’s outliers and then parading attractive young men in smart blue uniforms in front of them, recruiters were engaging in a highly effective kind of target marketing.

One of the main arguments of Benemann’s study is that such male intimacy is not merely an accident of life at sea but instead an important draw for many who chose sailing as a profession. The author’s case for this is convincing and enlightening. He begins, for instance, by noting that the sites for naval recruitment were saloons and boarding houses for transients—precisely the venues frequented by the marginalized—and that this placement was strategic. By visiting sites frequented by society’s outliers and then parading attractive young men in smart blue uniforms in front of them, recruiters were engaging in a highly effective kind of target marketing.

Benemann next looks at the romances of the times—tales of sailors held captive by Barbary pirates and the like. He notes that “the homosexual bent of the men of Barbary was an established tenet of nautical lore” and suggests that, far from acting as cautionary tales, these lurid stories of sexual slavery and same-sex attraction were actually a draw for some men. In this sense, men who felt trapped by the values of American society may have flocked to an exotic locale such as the Barbary Coast or Polynesia, where Western prohibitions against homosexuality did not apply.

The sexual implications of flogging are also examined in detail. As an official of the time reports: “The sailor prefers whipping to other punishments.” Tellingly, a visiting Englishman wrote: “It is a strange fact that a considerable portion of the sailors, and more especially that portion who oftenest suffer the infliction, believe that the service would be ruined if the custom of flogging were abolished in the Navy.” Even after other branches had abolished it as a form of punishment, the Navy was the one remaining branch where a man could get whipped. Benemann points out that floggings can be experienced as an eroticized public performance in which a nearly (or even fully) nude person is subjected to another man’s power. The author cites a study indicating that much of the erotic material consumed by sailors of the time involved scenes of flogging, and he reports that in all English pornography between 1840 and 1880, nearly half of it centered on scenes of flagellation.

Benemann also takes on the myth of the sailor with a woman in every port, which he debunks by arguing that, since whaling ships and other vessels did frequently stop at various places and were not often that long at sea without touching land, why would so many of the men choose to have sex with other men, were it not a matter of preference? He also highlights items such as the design of naval uniforms, which have always glorified and eroticized the male body, and points out that designating parts of the ship as “queer space” was as prevalent in World War II as it was in the War of 1812.

Benemann’s study is a very readable and insightful look at how—for at least a fair number of recruits, anyway—the Navy afforded a romance of the seas in more ways than one.

Dale Boyer is the author ofThe Dandelion Cloud, Thornton Stories, andJustin and the Magic Stone.