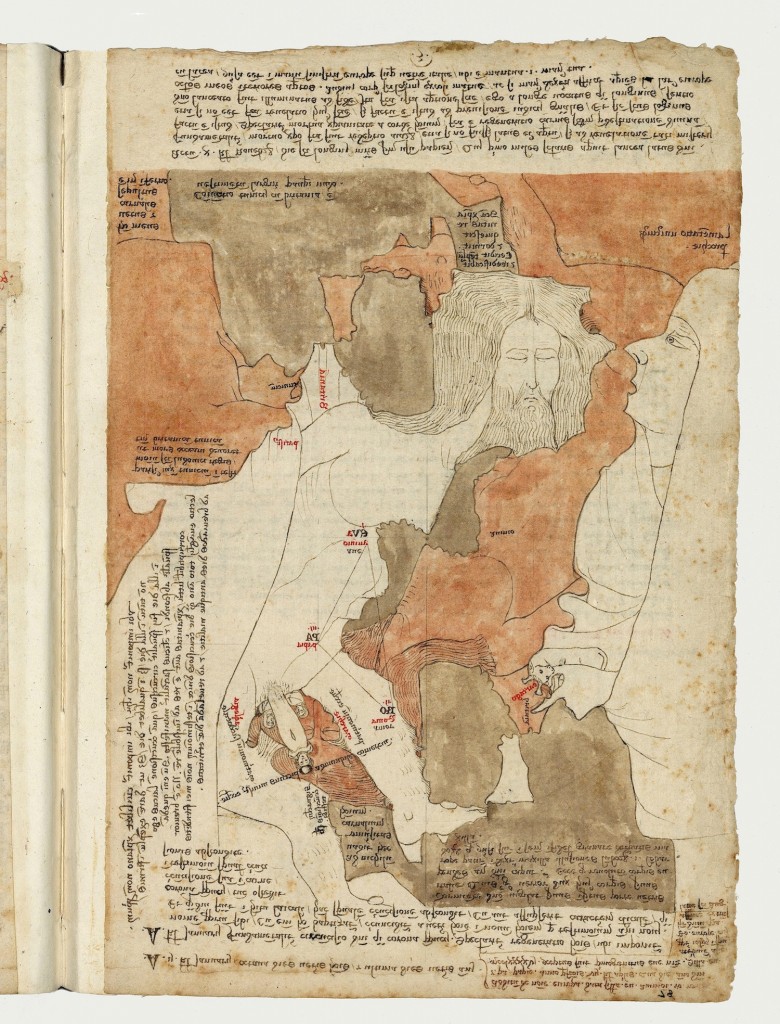

THE INTERSECTION of sex and the Catholic priesthood has long been fraught, and recent scandals involving priests and choirboys have revealed to the modern public that there’s considerable overlap between the two. But clerical celibacy and its effects have been long debated. That vows of celibacy do not automatically extinguish thoughts about sex (or actions on its behalf) has been an open secret of the Church and an occasional but recurring topic of public discussion since the Middle Ages, as witness this example: the image  reproduced here was drawn in the 1330s by an Italian priest named Opicinus de Canistris. Originally from Pavia, a small university town south of Milan, Opicinus lived at the papal court in Avignon, where he worked in the scriptorium by day and created drawings by night.

reproduced here was drawn in the 1330s by an Italian priest named Opicinus de Canistris. Originally from Pavia, a small university town south of Milan, Opicinus lived at the papal court in Avignon, where he worked in the scriptorium by day and created drawings by night.

The drawing before you is likely to be one of the strangest you’ve ever laid eyes on; it will take a moment just to explain what you are seeing.

So much for the drawing’s form; what about its content? The sleeping male figure of Europe is a personification of the Church. A label above his head identifies him, reading “Holy Christianity reposes and sleeps.” We can further identify this figure as Christ himself: we see nails in the figure’s two feet in Italy and Greece. Thus, the figure is a two-part personification: the Church has become a body, and this body is identified with that of Christ. That much is not so unusual, apart from its cartographic framing. Christian images had long used personifications and larger allegories to enliven and embody abstract ideas. But what actually happens when an idea becomes embodied? Opicinus, following a long line of other thinkers, believed that when a concept was given a body, the metaphor could then be elaborated to explain the meaning of that body’s parts. In a common medieval example, the “body politic” was read anatomically: the head was the king, the heart his counselors, the hands his knights, the legs his merchants, and the laborers his feet. Opicinus, however, takes this metaphor in an unexpected direction: at the drawing’s center, between Europe’s legs at the top of the Adriatic coast near Venice, he depicts himself as the penis of the Church!

The shock of this representation takes a moment to register. A medieval priest, making drawings at night in his room, has created a complex self-portrait as the penis of the Church, or, even more directly, a self-portrait as Christ’s penis. If everything in the world needed to be imbued with a higher meaning, as Opicinus believed, then the sexual anatomy of a male personification of the Church was no exception. When we look closely, we see the small figure emerging near Venice, between Europe and Christ’s legs. His body is streamlined and made phallic, with no arms and legs visible; his loose collar resembles a foreskin, his head making up the “head” of the penis, and two figures peeking out by his feet adopt the shape and scale of testicles.

If we stopped here and ignored the traditional academic protocol against wild speculation, we could have a field day with this image. Could this be the queerest image in Christian history—a portrait of the artist/priest as the object of his desire, his longing for Christ and hunger for cock merged into a single, shocking fantasy? Or is it an identification with what Opicinus may have seen as a straight symbol of phallic power? Are both of these speculations just a modern bias; could 14th-century viewers have seen the image nonsexually? As we will see shortly, Opicinus does explain himself, giving the image a kind of “meaning,” but let us pause for just another moment and appreciate its visual queerness before allowing a “responsible” interpretation to enter the picture.

The meaning that Opicinus found in this incredible representation will lead us in several directions, but ultimately to the question of what a metaphor like this one can reveal about the intersection of sexuality and the Church. But let’s first follow the logic of the drawings as Opicinus explains them. He offers two reasons for depicting himself in this way: one has to do with the way internal spirituality becomes marked on the body, and the other with the act of conversion, which he casts in sexual terms.

Like many medieval thinkers, Opicinus believed that one’s external appearance must mirror an interior state, a historical stance often used to justify exclusion and violence to the disabled, the deformed, or the ugly, whose souls were presumed to be as corrupt as their bodies. In the case of a priest, Opicinus thought that his internal goodness must be manifested on the outside of the body. To this end, for example, he crafted an elaborate argument related to circumcision. Despite the fact that medieval Christians were rarely circumcised, Opicinus wrote that a man’s circumcision could take place both physically—in the flesh—and spiritually. The “spiritual” circumcision was the sign of a covenant with God; Opicinus tells us that before becoming a priest his “spiritual” circumcision remained invisible to those around him, as there was no outer sign on his body that revealed his covenant with God. However, when he took holy orders, this internal “circumcision” was marked on his body through the external sign of the tonsure—the round patch of hair that monks and priests commonly shaved away on their heads. According to this logic, the priest who had a tonsure was a walking image of a circumcised penis. We see this reflected in the drawing: his loose collar appears as the cut foreskin, while the “head” bears the mark of the tonsure—the circle formed by the “O” of Opicinus’ name that is written above the figure. By wearing the tonsure, Opicinus—and all priests of his time—bared their heads as a sign of allegiance to God, a marker in the flesh analogous to circumcision.

Yet beyond this specific meaning, explained in the captions around this and other images, how can we understand the underlying concept of the priest as Christ’s penis? This question has far broader implications than those explained above in Opicinus’ narrow metaphor of circumcision. Medieval preachers and theologians often used the metaphor of the seed to describe the way faith takes root in the human heart—a common biblical metaphor. Christ was the original sower of the seed of faith in the human heart, but the priest assumes this role only after Christ’s death. What Opicinus has done is to take a common Christian metaphor—faith as a seed—and to literalize it with breathtaking directness. If faith is like a seed implanted in the body or heart, the priest is analogized as the farmer. And what part of the body plants the seed? Depicting the priest as the penis of the Church emphasizes and elevates the role of the priest in spreading faith through the word of God.

It is within the context of this metaphor—the priest as the sower of seed—that Opicinus makes his most shocking statement. In a short text alongside this drawing, he writes about the role of the priest in converting and creating the Christian people. Creating new Christians, he writes, requires reproduction, and the priest takes on this seminal role. He writes: “Behold the member [penis]of Christ in the Christian people. … I approach the stomach or womb, the mistress of her God (that is to say, the individual parish and servant of the universal Church). … Intending to generate a people in the name of my Lord, swollen with the knowledge of preaching, I entered through violence” (emphasis mine). In this incredible passage, Opicinus alludes to a situation described elsewhere in his work: arriving in an unfriendly and unfamiliar town or parish and needing to convert or lead people who didn’t want him there. Within the sexual metaphor he has created, he is saying that the priest, as the Church’s penis, must sometimes metaphorically rape his flock in order to create new Christians. He has moved us from a conventional metaphor (faith as a seed) to a highly unorthodox one (conversion as rape) as enabled by the swelling of the penis with the blood of knowledge.

IN THE FACE of all of this strangeness (which does follow a kind of logic), generations of scholars have claimed that Opicinus was mentally ill. Was he? I don’t think it particularly matters. His drawings reveal something elemental about the power of the sexual metaphor in medieval Christianity. It starts small and expands outward, moving across boundaries of convention and safety until we arrive somewhere… uncomfortable. It starts, perhaps, through a core feature of celibacy: that many of the creators of these sexual metaphors probably never had actual sex.

What’s more, it was not only the men of the Middle Ages who created these metaphors; countless sources survive in which female mystics characterize their spirituality in sexual terms. The delight of union with God is described in ways that relate it to the pleasures of sexual intercourse (which, presumably, most nuns had never experienced). Men, too, described union with a male God in sexual terms: a German monk named Rupert of Deutz, who lived in the 12th century, describes a vision in which he embraced and kissed a sculpted image of Christ, which responded by coming to life and opening his mouth so that they might kiss more deeply.

Still, the question remains: why have so many celibate Christians throughout history explained aspects of the religious experience—appearance, conversion, union—in sexual terms? Certainly a cynical argument would point to the heightened interest (even obsession) sparked by the sexual deprivation of celibacy. But it might be argued that such metaphors were part of a strategy to cast meaning in ways that non-celibate readers or audiences would understand, sex being a nearly universal human experience. Regardless of how we view their intent, they did sometimes get the sex thing stunningly wrong, which I think is the case with Opicinus’ use of rape as a metaphor for Christian conversion.

I opened with a reference to recent scandals involving priests having sex with underage boys, which seem related to priestly celibacy but otherwise so hard to explain, and I wonder if the creation of these sexual metaphors within Christian discourse could have a role to play in how we think about these issues. What happens when sexuality is removed from the lived experience of human bodies and translated into metaphorical or allegorical images or ideas? What becomes of sex when it’s removed from the realm of experience and treated as a discursive subject—as a tool for talking about something else entirely? To begin with Opicinus, it’s hard to say whether his symbolic notions—the priest as a penis on a mission, swollen with self-importance, conversion as an act of rape—ever crossed the boundary from thought to action. But if we believe that these are more than the eccentric musings of a man who clearly thought about sex, we might see that a total lack of experience with sex could lead to some unfortunate results.

Our experience with sexual abuse in the contemporary Church revives this fundamental question. Do those for whom sex is purely hypothetical rather than something experienced fundamentally misunderstand the complications and consequences of sexual actions between real bodies? In Opicinus, at least, we see a kind of play with the words and metaphors of sexuality such that one imaginative claim leads to others, with meanings piling upon meanings. There’s an imaginative joy to it, to be sure, a sense that he’s having fun playing with images and ideas. One can only imagine the consequences of mistaking these phantasmagorias for sex in the real world and endeavoring to act upon them. About Opicinus we will never know, but the recent, very real sexual abuses by priests, as inexplicable as they are, can perhaps be explained in part by a similar lapse into fantasy and delusion.

Karl Whittington is assistant professor of history of art at Ohio State University. His first book, Opicinus de Canistris and the Medieval Cartographic Imagination, was published in 2014.

Discussion3 Comments

I believe that the passions of Christ go deeper than the prohibitions laid down as dogma. I don’t believe it would have been Christs intent to preach celibacy as a form of oppression. It seems that we are missing his sole relationships with the apostles when we view it this way. It may be that to expose Christs genitalia was very much in modern day thinking with the expression “Bless My Soul” It seems that the hidden sexuality would also have to be sacred. It is interesting to inquire on what the reaction would be if we were ever truly exposed to God’s genitalia. I feel the response maybe more diverse and in keeping with the salvation we need in our climate today in the twenty first century. Surely this view of the body would not be oppressive and may even show some grace for those who feel sexuality and same sex relationships are have been exploited by a corrupt or perverted form of sin.

Am I viewing the illustrations to this article correctly or have they been printed in reverse? Spain appears to be to the East of Italy and Greece. The triangulation between Avignon, Pavia and Rome is in the wrong orientation and the abbreviated names of these cities are backwards. Even the name of Opicimus himself centered on Christs penis is only readable when viewed in a mirror!

The illustration is backwards – hold to a mirror and you can see the map of southern Europe clearly, as well as making the writing legible (albeit in the language chosen by the illustrator).