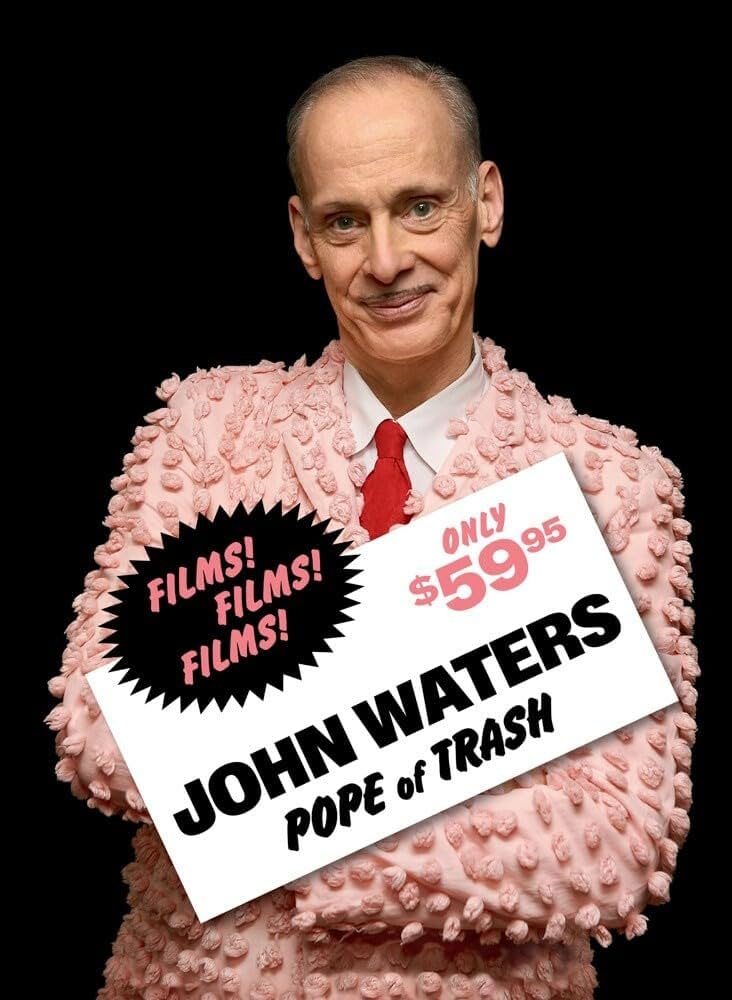

JOHN WATERS

JOHN WATERS

Pope of Trash

Edited by Jenny He and Dara Jaffe

DelMonico Books. 255 pages, $59.95

IN THE SUMMER OF 1981, my father took me and my brother to see a double feature of two John Waters movies: Female Trouble and Pink Flamingos. I was fourteen, and my brother was three years older. My family had recently seen Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert review Pink Flamingos on their weekly TV show, and when my father learned that two Waters films were playing at the Nickelodeon Theater in Boston, he decided to take me and my brother to see them. My mother was not a fan of art films and declined to join us, perhaps wisely.

Female Trouble (1974) was shown first, and this campy tale of juvenile delinquent Dawn Davenport’s journey from teenage runaway to hideously disfigured and murderous performance artist appealed to my budding (but still closeted) gay sensibilities. As a fourteen-year-old gay boy, I was thrilled to see the titanic and terrifying drag queen Divine play a Catholic school girl, and the eccentric Baltimore actress Edith Massey strut around in a lace-up leather catsuit and Frederick’s of Hollywood heels. But despite its gory ending and freaky sex scenes, Female Trouble still didn’t quite prepare me for Pink Flamingos (1972), the second film that day. Technically a comedy, Pink Flamingos is also an onslaught of shocking imagery. Two people kill a live chicken on-screen by crushing it between their bodies during sex. A creepy manservant masturbates into his hand, and then uses a syringe to impregnate women imprisoned in a pit with his semen. The protagonist, played by Divine, fellates her adult son as he moans “Oh, Mama, I should have known you’d be better than anyone.” And, most famously, after tarring and feathering her enemies and executing them with a gun, Divine eats actual dog excrement, rolling it around on her tongue like a delicious treat. All of these atrocities were performed by nonprofessional actors in cheap, garish costumes, delivering their lines in loud, declamatory style.

I suppose some parents would have grabbed their kids and walked out, but my father didn’t. He had driven us all the way into the city and paid for our tickets. No cinematic atrocities could outweigh those sunk costs. We sat through both movies, back to back, but there was little conversation in the car ride home. I think we were all in shock at what we had seen.

I’m grateful that my father took us to see the double feature, both for the experience and for the cultural capital it gave me as a high school freshman. Certainly, I was the first of my friends to see those films. Despite my appreciation, though, I would have laughed if anyone told me John Waters would someday receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, which he did in September 2023. The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in L.A. is also hosting “John Waters: Pope of Trash,” a year-long exhibit honoring Waters and his films. The Museum is affiliated with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the same people who bring us the Oscars every year. Along with the exhibit, the Museum has issued a handsome hardcover catalogue, also titled John Waters: Pope of Trash, which has essays from scholar B. Ruby Rich (the current editor of Film Quarterly) and David Simon (the award-winning producer of The Wire), among others. The book is large, full of beautiful photos, and suitable for displaying on a coffee table. It is downright tasteful. The Hollywood star, the museum exhibit, and the book are huge honors for John Waters. It’s been a long, strange trip to mainstream acceptance for Waters, an auteur who specializes in what he calls “art-exploitation” films and who was dubbed the “Pope of Trash” by William S. Burroughs in 1986. Waters was born in 1946, in Baltimore, and grew up in that city’s suburbs. The city has remained central to his work and his life. Unlike many queer people who leave their hometown to find freedom, Waters has kept his Baltimore roots and filmed all of his movies there. His parents were supportive of his creative endeavors, despite occasionally being horrified by them, and some of his earliest films were shot at their home. His father even helped him create some props, including a narcotics-dispensing vending machine for the short film Eat Your Makeup (1968). Born Harris Glenn Milstead, Divine befriended Waters during high school and appeared in several of his early shorts. Waters soon made Divine his preferred leading lady and gave him starring roles in Multiple Maniacs (1970), Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, Polyester (1981), and Hairspray (1988). Divine became notorious for the shocking things he did in Waters’ early films, like eating that infamous dog poop, being raped by a giant lobster, and bouncing on a trampoline while shoving dead fish in his crotch. (Note that Divine identified as male and used he/him pronouns.) Divine used his notoriety to launch a mainstream show business career, but unfortunately it was cut short. The night before he was to start filming a recurring role on the popular sitcom Married with Children, Divine died of a heart attack at age 42. Divine’s death was a huge emotional shock for Waters, but he continued on and made five more feature films. Much like Divine, Waters used his own notoriety to go mainstream and attract bigger-name actors to his films. This process began even before Divine’s death, with 1950s heartthrob Tab Hunter starring in Polyester as Divine’s love interest, and Debbie Harry, Sonny Bono, and Jerry Stiller appearing in Hairspray. These performers may not have been the biggest Hollywood stars, but they were still better known than Waters’ usual stable of Baltimore actors. After Divine’s death, Waters began to attract and cast even bigger stars in his movies: Johnny Depp in Crybaby (1990), Kathleen Turner in Serial Mom (1994), and Melanie Griffith in Cecil B. Demented (2000). In minor roles, he cast cult figures like rocker Iggy Pop, celebrity hostage Patty Hearst, and Warhol superstar Joe Dallesandro. Waters didn’t ask any of these actors to eat dog poop or have sex involving live poultry, but that’s because his style began to change after Desperate Living (1977). His films of the 1960s and ’70s were deliberately made to shock audiences. In addition to the disturbing scenes in his well-known movies like Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble, Eat Your Makeup includes a re-creation of the JFK assassination with Divine as Jackie Kennedy, while Multiple Maniacs features a carnival sideshow of fetishists and a sex scene in a church involving Divine, a rosary, and visions of the life of Christ. And, in Desperate Living, a dog eats a dismembered penis and prisoners eat maggots. The film ends with a cannibalistic feast. But beginning with 1981’s Polyester, Waters reduced the shock value and tried another approach. Its plot does include murder, a violent foot fetishist, and teenage abortion, but Polyester, a parodic homage to Douglas Sirk-style women’s films, is much less graphic than his previous movies. Also unlike his previous movies, which were X-rated or unrated, Polyester received an R rating and wider distribution. Critics took note of this new approach, with Janet Maslin writing in The New York Times that Polyester’s “comic vision is so controlled and steady that Mr. Waters need not rely so heavily on the grotesque touches that make his other films such perennial favorites on the weekend Midnight Movie circuit. Here’s one that can just as well be shown in the daytime.” The film did feature Odorama, a scratch-n-sniff promotional gimmick with scents like skunk and flatulence, but Polyester was a big step towards mainstream acceptance. Most of his subsequent films took the same approach by tackling controversial subjects, but in a relatively acceptable way. As John Waters: Pope of Trash points out, certain themes and topics run through all of Waters’ work, from his first shorts to his more mainstream features. His later films may be less overtly shocking, but they are still easily recognized as “John Waters movies” because they humorously explore and critique the same aspects of American culture as his earlier ones. Waters is gay, but queer characters and culture are not the main focus of his work (with the exception of Desperate Living, which has lesbian protagonists). Rather, he applies a queer or camp sensibility to examine and parody heterosexual social norms, particularly the nuclear family. It’s an approach that has won him a wide audience. Queer people go to John Waters’ films to see movies made by one of their own, while straight audiences attend to laugh at how their lives are portrayed onscreen. The American family, particularly in its suburban mode, is subverted, stressed, and stretched to its breaking point in many of his works. For example, in Pink Flamingos Divine’s mother (Edith Massey) spends her days in a playpen eating eggs, and Divine’s character has sex with her son, while in Female Trouble, teenage schoolgirl Dawn Davenport assaults her parents on Christmas morning for giving her the wrong type of shoes and runs away from home to have a daughter out of wedlock, whom she eventually murders when the daughter grows up to be a surly adolescent. In Polyester, Waters flipped the script, this time casting Divine as Francine Fishpaw, a long-suffering suburban housewife who’s married to a cheating, abusive spouse while raising violent adolescent children. And, in Desperate Living, Waters’ longtime collaborator Mink Stole plays Peggy Gravel, a wealthy suburban housewife who incites her maid to murder her husband, comes out as a lesbian, and murders the outcast denizens of a small village with a man-made rabies epidemic. Another murderous housewife is the focus of 1994’s Serial Mom, where Beverly Sutphin murders neighbors who don’t meet her high standards of behavior. As you might guess from those brief plot summaries, Waters is also fascinated by crime. The director used to attend courtroom trials for entertainment and has a large collection of newspaper clippings about serial killers. Criminals appear in almost all of his films. He has a particular fondness for juvenile delinquent characters, whether the aforementioned Dawn Davenport, Johnny Depp as Crybaby Walker in Crybaby, the Fishpaw siblings in Polyester, shoplifting sidekick Matt in Pecker, or Tracy Turnblad and her friends in Hairspray. Many of these characters are broad caricatures of the dangerous teenagers the media warns us about, but in Hairspray, Tracy Turnblad breaks the law and defies her parents for a good cause: to integrate The Corny Collins Show, a racially segregated TV dance show similar to American Bandstand. She’s a juvenile delinquent with a political agenda. Waters based The Corny Collins Show on The Buddy Deane Show, which aired in Baltimore when he was a teenager. In Hairspray, Tracy’s rebellion successfully integrates the show, but in real life The Buddy Deane Show was canceled, possibly due to protests from both pro- and anti-integration activists. Perhaps because of its feel-good message, Hairspray has become the most popular of Waters’ films, spawning a Broadway musical and, in turn, a film version of the musical. The renegade filmmakers who kidnap actress Honey Whitlock (Melanie Griffith) in 2000’s Cecil B. Demented are perhaps too old to be juvenile delinquents, but they’re still young enough to think they can destroy the Hollywood system. They’ve tattooed their arms with the names of their favorite directors, including Fassbinder, Otto Preminger, and Kenneth Anger. Waters’ deep love of cinema—from the exploitation films of Russ Meyer and Herschell Gordon Lewis to the highbrow art films of Pasolini—is on display in many of his movies. Todd Tomorrow, the handsome hunk played by Tab Hunter in Hairspray, owns an artsy drive-in movie theater showing a Marguerite Duras triple bill. Movie posters, including one for Pasolini’s Teorema, decorate the home of the villainous Marbles in Pink Flamingos. The title character in 1998’s Pecker ends the film resolving (or threatening?) to become a filmmaker himself, but most of Pecker is about how his amateur photography garners the attention of the New York art scene. Art and the art world are another of Waters’ obsessions. Artists of all kinds appear in his films: painters, singers, dancers, performance artists, musicians, even fiber artists like Lulu Fishpaw in Polyester, a delinquent teen who finds redemption through macramé. Waters has a rich knowledge of cinema history, but where does he fit into that history? B. Ruby Rich’s essay, “From Underground Movies to the New Queer Cinema,” positions him as an important bridge between America’s early underground gay filmmakers (like Kenneth Anger, the Kuchar Brothers, and Andy Warhol) and the filmmakers of the 1990s who are considered part of the New Queer Cinema (a term Rich herself coined), such as Todd Haynes, Cheryl Dunye, and Gregg Araki. Waters has acknowledged the influence of George and Mike Kuchar, the twin Bronx filmmakers who made hundreds of often tawdry shorts starring their friends. In turn, Waters’ own influence can be seen in the work of the New Queer Cinema directors, whose films often focused on similar themes: crime, social outcasts, the American family, and troubled teenagers. After reading Rich’s essay, I thought of how Gregg Araki’s films, such as The Doom Generation (1995) or Nowhere (1997), with their garish costuming, deliberately stagey dialogue, and troubled young people, take aspects of Waters’ work and use them in a more æsthetic and erotic way. And, much like Waters, Todd Haynes made his own Douglas Sirk-inspired film, Far from Heaven (2002), while Haynes’ most recent film, May December (2023), is focused on a dysfunctional suburban family with a monstrous mother. Julianne Moore’s character in that film, a quietly psychotic cake-baking mom who’s married to the man she seduced when he was only thirteen, is clearly a cousin to the serial moms and abusive mothers Waters featured in so many of his classics. Like Waters, Haynes is a gay man using a camp sensibility to examine straight social norms. The New Queer Cinema directors didn’t shy away from portraying sex, and sex, particularly of the fetishistic variety, is also a subject Waters has returned to repeatedly. Waters has spoken often about his fascination with sexual fetishes, and fetishists of all kinds appear in his movies, including voyeurs, foot fetishists, adult babies, and leathermen. Multiple Maniacs features Lady Divine’s Cavalcade of Perversions, a carnival sideshow of sexual fetishists, including bicycle seat sniffers, puke eaters, and armpit lickers. These fetishes may not be your thing, but that’s okay. Sex scenes in John Waters’ movies are played either for laughs or for shock value, not for erotic impact. Waters made his first film, the short Hag in a Black Leather Jacket, in 1964. His last, the feature-length A Dirty Shame, was made in 2004. In total, he’s written and directed sixteen films over his forty-year career, twelve of them feature-length, and all them have included actors and designers from Baltimore. His childhood friend Mary Vivian Pearce has appeared in every Waters film, with lead roles in Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble. Waters dressed and styled Pearce to look like 1940s actress Jean Harlow, but far more famous than Pearce was Waters’ muse, whom he envisioned as Jayne Mansfield and named after a character in a Jean Genet novel: Divine.

Waters made his first film, the short Hag in a Black Leather Jacket, in 1964. His last, the feature-length A Dirty Shame, was made in 2004. In total, he’s written and directed sixteen films over his forty-year career, twelve of them feature-length, and all them have included actors and designers from Baltimore. His childhood friend Mary Vivian Pearce has appeared in every Waters film, with lead roles in Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble. Waters dressed and styled Pearce to look like 1940s actress Jean Harlow, but far more famous than Pearce was Waters’ muse, whom he envisioned as Jayne Mansfield and named after a character in a Jean Genet novel: Divine.

Peter Muise is author of Legends and Lore of the North Shore (2014) and Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts (2021).