KEITH HARING

KEITH HARING

Art Is for Everybody

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

April 27–September 8, 2024

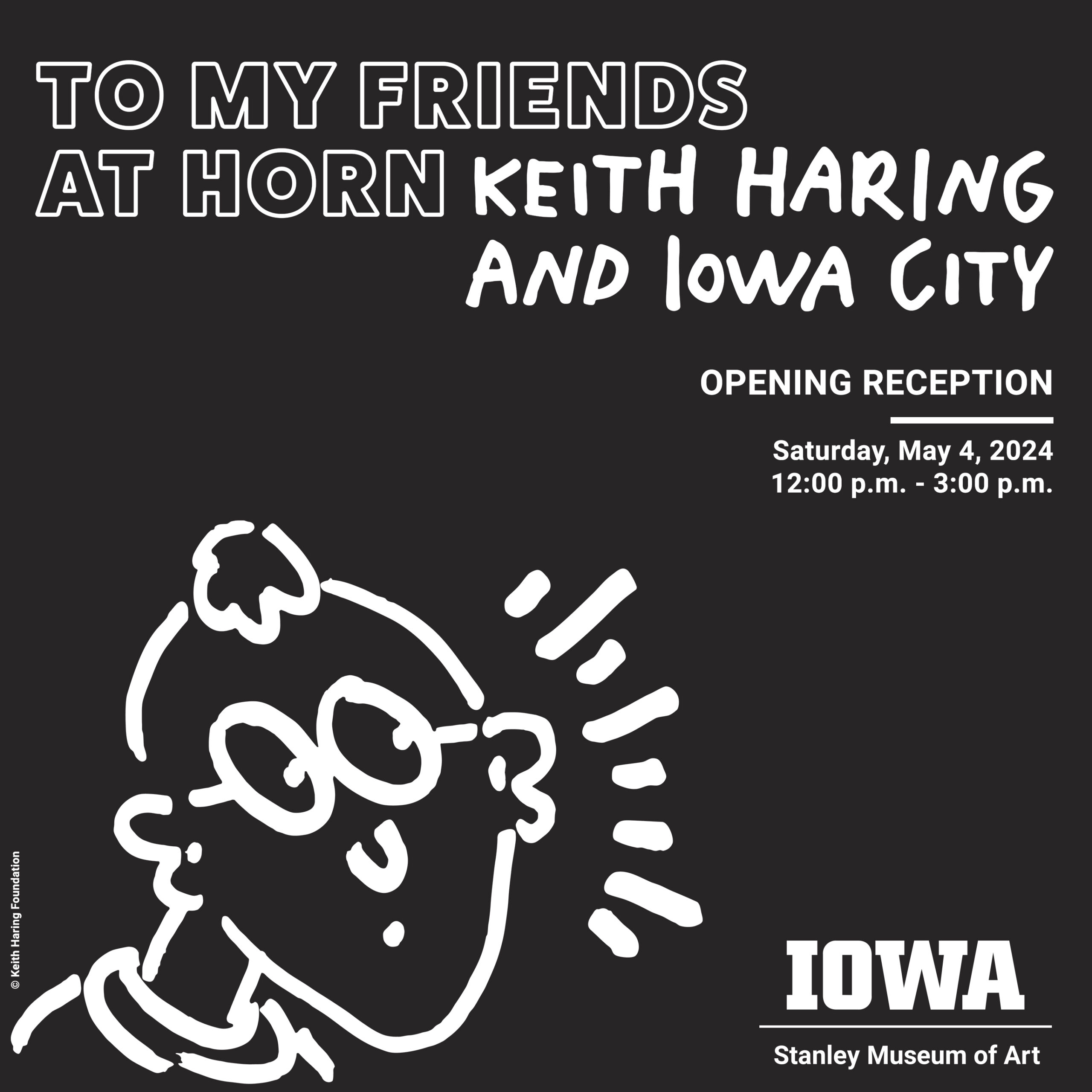

TO MY FRIENDS AT HORN

TO MY FRIENDS AT HORN

Keith Haring and Iowa City

Stanley Museum of Art,

The University of Iowa

May 4, 2024–January 27, 2025

IS ANY OTHER ARTIST simultaneously as well-known and as little understood by the general public as Keith Haring? Viewed out of context, the simplicity of his iconic characters—the crawling baby, the barking dog, the stripped-down and gyrating human form—makes them easily digestible, even to non-art lovers. Through the work of the Keith Haring Foundation, they are also ubiquitous in marketing, from T-shirts to branding for organizations like Best Buddies International. The small-town boy from Kutztown, Pennsylvania, certainly did make it big.

This leads, however, to the main criticism lobbed at Haring’s work:artwork that’s this popular cannot be “great” art. As a friend of mine told me when reading Brad Gooch’s recent biography of Haring, he has always seen Haring as “lightweight” and “a Johnny One Note—same palette and images again and again.” Fortunately, two exhibits appearing this past summer in stellar Midwestern museums—the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the University of Iowa’s Stanley Museum of Art—help blunt this critique. In tandem, they deepen and reinforce an understanding of Haring’s role as an art populist, while also highlighting the ferocity of his political messaging.

Haring’s populism, his desire to bring art to the masses, serves as the most prominent theme in both shows. This is captured most succinctly in the title of the show Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody (which traveled from Los Angeles and Toronto to arrive in Minneapolis, and features an expansive catalogue). The statement in the title is drawn from a journal entry early in Haring’s career, where he also declared: “The public has a right to art.” The show promotes Haring’s commitment to this ideal in an early room featuring life-sized, multi-screen slideshows of Haring creating his famed chalk drawings in the New York City subways of the early 1980s. Numerous works, from posters to videos to photographs of Haring’s many site-specific murals, demonstrate their origin in his desire to bring art out of its predictable gallery setting and into spaces where the public would be more likely to experience it.

A cynic might say that all this was spurred by Haring’s desire for greater fame, an argument perhaps buoyed by the opening of the Pop Shop in 1986, where the artist’s icons were affixed to every imaginable piece of merch. Indeed, the curators miss an opportunity to discuss more fully the tension between marketability and messaging in Haring’s art, beginning with how, in the wake of his death from AIDS in 1990, Haring’s social and political messages have often been sidestepped in favor of more commercial uses of his images.

Fortunately, the exhibit gives great emphasis to Haring’s political consciousness and its role in his art. Even before Ronald Reagan contributed, through his silence, to the decimation of the gay community by AIDS, Haring saw the danger in his administration’s right-wing reactionism. Using a series of cut-up newspaper headlines in 1980, Haring collaged messages like “Reagan: Ready to Kill” (juxtaposing a headshot of the president and a photo of a Ku Klux Klan grand wizard burning a cross) or “Reagan Slain by Hero Cop.” Haring’s desire for his art to contribute to social change is everywhere in evidence, from anti-drug messages, such as the famous “crack is wack” mural along a New York City highway, to safe-sex flyers, from anti-apartheid posters like 1985’s Free South Africa series to numerous works warning against nuclear proliferation and environmental degradation. The work can still disturb and provoke. The massive painting Michael Stewart—USA for Africa links graffiti artist Stewart’s brutal death at the hands of the New York City Transit Police to the ongoing destruction of human life in mid-1980s Africa. Numerous figures cover their faces, refusing to look either at Stewart’s strangulation—foreshadowing more recent deaths, from Eric Garner to George Floyd—or the river of blood gushing from a severed globe. Anyone believing Haring’s art to be “lightweight” has not delved deeply enough.

To make good on his “art is for everybody” dictum, Haring made a concerted effort to bring his work to audiences of children. This forms the main focus of the Stanley Museum’s show To My Friends at Horn: Keith Haring and Iowa City. In 1984, Haring traveled to Iowa City at the invitation of Colleen Ernst, a teacher at Ernest Horn Elementary School who had introduced his art to her “fascinated” fifth- and sixth-grade students. While much of Haring’s three-day visit was geared to adults, completing a large painting at the Old Capitol building and lecturing at the Stanley, he also gave workshops to the schoolchildren. This led to a return invitation in 1989, less than a year before Haring’s death from AIDS, where he gave a one-day painting demonstration to the children, incorporating their ideas extemporaneously into the mural A Book Full of Fun in the school library.

Both paintings are included in the Stanley exhibit. In the 1984 work created at the Old Capitol, headless human figures ride a centipede, its own head replaced by a computer monitor whose screen is filled by a massive dollar sign. On one edge, a man attempts to run away, but is about to be trampled by the monstrous insect. This commentary fits into a larger anti-materialist motif within Haring’s art, but it doesn’t touch on sex or race in a way that might have made an artist invited to an elementary school persona non grata. Letters from Haring surrounding his 1989 visit show that he was sensitized to his position as a gay man and a person with AIDS coming to work with children, knowing that parents aware of either of these statuses could be hostile. Being an art ambassador required code switching. To My Friends at Horn includes Haring’s AIDS poster Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death, also from 1989, alongside A Book Full of Fun’s colorful cartoons of scattered letters and numbers, dancing animals, and tumbling humans. (Five days after Haring completed this mural, to the evident delight of the schoolchildren, he put the finishing touches on Once Upon a Time…, his sexually explicit mural in the men’s bathroom of the Lesbian & Gay Community Center in New York City.)

Philip Clark, who lives near Washington D.C., is completing a biography of the gay publisher H. Lynn Womack.