Keith Vaughan

Keith Vaughan

by Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings

Lund Humphries. 184 pages, $80.

Keith Vaughan: The Mature Oils 1946-1977:

Keith Vaughan: The Mature Oils 1946-1977:

A Commentary and Catalogue Raisonne

by Anthony Hepworth and Ian Massey

Redcliffe Press Ltd. 208 pages, £40.

IN ONE of his last journal entries, the British painter Keith Vaughan wrote: “Another day nearer the end. Slept rather better during the day. Had several de- lightful dreams lately that I was working again and producing paintings which pleased me. Felt marvelous at the time. Alas only a dream.” Vaughan is known as much for his journals as for his paintings. The journals span nearly four decades from his experiences of World War II, to his successful career in the 1950s and 1960s, through to his bouts with colon cancer and ultimately suicide in 1977. Since their publication in the early 1990s, these journals, with their precise and lyrical details of activities and emotions, have be- come another way of making sense of his creative and sexual life.

Take his description after watching a soccer game: “legs and things of footballers. Watched this evening trying to dis- cover whether a padded crotch covered their genitals. Like to see them play naked—or better to strip naked after the match and stand still. Examine them minutely. Such stamina, skill and vital charm.”

His descriptions of landscapes were equally engaging. In describing the landscape of southern Spain seen from his first airplane ride, he crafted a mixture of observation and sensa- tion: “a basking ochre panorama of incredible subtlety and de- tail, everything conforming beautifully to the geological formations. No trees. Rather pleasant the bumping sensation when going through turbulent passages of air because it gave the feeling, if one didn’t look out, that there was something solid underneath.” These journal entries point to two aesthetic obsessions in Vaughan’s work throughout his life: the impor- tance of male figures and the patchwork solidity of his land- scapes.

While his life and paintings were ignored for some years, interest in Vaughan’s work has been on the incline of late, no- tably last year, which marked the centennial of his birth. Keith Vaughan, by Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings, and Keith Vaughan: The Mature Oils 1946-1977, by Anthony Hepworth and Ian Massey, are two recent books that offer new encoun- ters with this artist. Both books do a fine job placing Vaughan in his rightful place in 20th-century modernism,

Born in Sussex in 1912, Vaughan was the older of two sons. His father, an engineer, traveled far from England during Vaughan’s early life, first during World War I and later in Africa. In the 1920s, his father left his mother for another woman. A few years later, his father died an early death, leav- ing a layered emotional scar on the young Vaughan.

He attended Christ’s Hospital School in the 1920s, and, as he later recorded in his journal, endured bullying and abuse for his lack of enthusiasm for sports and his introspective lean- ings. But it was there that his interest in art began to take shape. After leaving school at the age of seventeen, he moved with his mother to North London. He found work in an advertising agency learn- ing the skills of design and photography.

As war approached, Vaughan registered as a conscientious objector and was drafted into the Pioneer Corps, working both in sol- dier hospitals and later in a German pris- oner of war detainment camp in the south of England. His brother enlisted as an RAF pilot and after only a month of service was shot down and killed in 1940. In remembering their last encounter, in London’s Trafalgar Square, Vaughan wrote: “A casual wave of the hand and a smiling glance was all the ceremony, although we each knew it was unlikely we should meet again.” Vaughan carried this loss through his work in the ambulance service and in the hospitals in Kent, where he struggled through the unsettling rou- tines of caring for seriously injured British soldiers and German prisoners of war. He was once fined for setting up his easel in the fields to draw the men working near the detainment camp. But it was his encounters in the Pioneer Corps that connected him with other writers and artists who expanded his ideas about and enthusiasm for painting.

Hepworth and Massey’s book anchors itself to Vaughan the artist and provides a rich catalogue of all the paintings he created from 1947 to his death in the late 1970s. Ian Massey in his essay “Walled Gardens” notes that the death of Vaughan’s brother and his work in the hospital “were to res- onate in his art for the rest of his life.” Massey maintains that the war experiences are crucial to understanding much of the flat but colorful paintings of male figures alone and assembled that Vaughan would create through much of his life. In con- sidering his works of the 1950s, Massey describes them as “lamentations for the dead,” or as a “commemoration and catharsis” that recaptures the loss of his father in childhood, his brother in the war, the wounded soldiers he tended, and the many lost friends and lovers through the 1930s and ’40s. What Massey gives us is a more private reading of the artist’s paint- ings coupled with the rich details of his journal.

The Vann and Hastings book provides more insight into the historical and cultural context for Vaughan’s art. Vann’s won- derful and extensive essay “The Intimate Figurative Impulse” places Vaughan within a constellation of other modernist artists, paying special attention to the in- fluence of Picasso and Matisse on Vaughan’s æsthetic styles. It was to these pre-war modernists that Vaughan’s art is most tethered, his canvases a constant ex- ploration into the abstraction of figures and landscapes.

Vaughan was never much inter- ested in the Abstract Expressionists. In 1956, he attended the Modern Art in the United States exhibition at the Tate Gallery, finding the work overwhelming and unsettling. In his journal he quoted poet Randall Jarrell’s critique of the art: “A universe has been narrowed to what lies at either end of a paint brush.” Vaughan compared these works, which he saw as lacking depth, to “well-designed posters.” The fact that he embraced forms, that he rejected the power of Abstract Expressionism, might also accounts for some of the neglect that his work has suffered over the years.

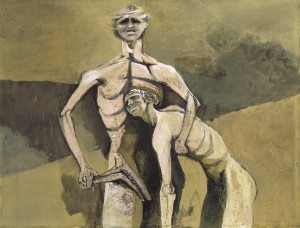

What mattered to Vaughan was the human form, which he often pictured as flat and heavy, and always as male. Indeed, his series of “assembly” paintings in the 1960s creates won- derfully mysterious scenes of men gathered together, in groups or in pairs, inhabiting a landscape that’s bare and empty. They all stand naked in some kind of primordial scene that mixes both quietness and a compelling attraction. Such paintings of men together and alone are the most striking can- vases of his œuvre. Their faceless anonymity in unspecific landscapes underscores their uniqueness as much as their uni- versality. These are figures searching for connection—and often finding it. But they are also male figures presented to- gether for our gaze. It is this element of Vaughan’s work that was so subversive at the time.

Writing in 1951, John Berger described Vaughan’s male nudes as “poetically compelling” and compared their naked- ness to “trees stripped of their bark.” For Berger, the æsthetic naturalism of the scenes held their own powerful mystery. But as Vann usefully reminds us, the paintings and drawings that Vaughan was producing in the 1950s made homoeroticism it- self an affirmative and subversive act. The atmosphere of the era would see the chemical castration of Alan Turing and the arrest and conviction of Sir John Gielgud after a police oper- ation in a Chelsea public bathroom, among other high-profile homosexual panics in post-war London. “In such a climate,” writes Vann, “Vaughan’s redemptive paintings and drawings of the male nude … had an inestimable value and significance.”

These two books provide a much needed reconsideration of the value and significance of an artist whose work has re- mained on the margins for too long.

James Polchin teaches writing at NYU and is the founder and editor of the site Writing in Public.