WHEN REVIEWING a recent book for The New York Review of Books, writer Larry McMurtry opened by indulging in the old thought experiment of deciding what one author’s works he would take with him to the proverbial desert island. His choice was none other than Gore Vidal. Noting that Vidal’s oeuvre encompasses 46 books that cover the gamut from historical novels to satirical plays and screenplays, literary essays, and political memoirs, McMurtry explained that Vidal has “a prose style that should be the envy of the dwindling few who realize that prose style matters.”

Born at West Point Academy on October 3, 1925, the grandson of Oklahoma’s first senator, T. P. Gore, and the son of Eugene Vidal, who served in the Roosevelt administration after founding three airlines, Vidal  grew up in a world of politics and privilege, attending private academies before joining the Army Reserve in 1943. While he contemplated running for office in his early career, the writer side of him won out and —except for an unsuccessful run for U.S. Congress in 1960 and a primary bid for the Senate in 1982 —has continued to trump his hankering for direct political involvement throughout his life. However, his interest in politics —his reliably liberal stance and his radical critique of “the American Empire”—is reflected in many of his novels and plays.

grew up in a world of politics and privilege, attending private academies before joining the Army Reserve in 1943. While he contemplated running for office in his early career, the writer side of him won out and —except for an unsuccessful run for U.S. Congress in 1960 and a primary bid for the Senate in 1982 —has continued to trump his hankering for direct political involvement throughout his life. However, his interest in politics —his reliably liberal stance and his radical critique of “the American Empire”—is reflected in many of his novels and plays.

Vidal’s third novel, The City and the Pillar, which he published at the tender age of 22, is one of the most thoroughly homosexual books he ever wrote and arguably the first overtly “gay” American novel. As such, it was destined to provoke a scandal—the year was 1948—and it helped to launch Vidal’s reputation as America’s literary enfant terrible. That image was bolstered twenty years later when he wrote Myra Breckenridge, whose transgendered title character reappeared in Myron in 1976. By then, Vidal was already well known as a staple on talk TV, notably Johnny Carson’s show, at a time when it was still possible for a “public intellectual” to go on the tube and shock America with the truth about their alienated lives and immoral wars (he was an early opponent of Vietnam).

The book under review by Larry McMurtry (who co-wrote the screenplay for Brokeback Mountain) was Vidal’s latest, Point to Point Navigation, a memoir that finds the author coming to grips with the loss of his companion of over fifty years, Howard Auster, who died in 2003. As always, Vidal’s personal drama unfolds against the backdrop of a larger political and historical tableau, in this case the spectacle of George W. Bush’s America as it sinks deeper into war, debt, and autocratic rule. The book’s title refers to Vidal’s flight service during World War II—a method of visual navigation in which one flies from one landmark to the next—and is apparently meant as a metaphor for his life’s course to date. A follow-up to his 1995 memoir, Palimpsest, the new book returns to Vidal’s early years but focuses mostly on the second half of his life.

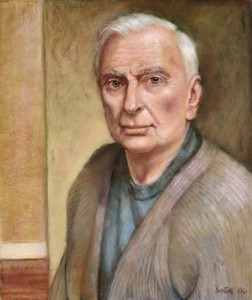

Now residing in the Hollywood Hills, the octogenarian uses a cane to get around a large house filled with books, art, and a very large cat, who sat with us during the interview.

— John Esther

Gay & Lesbian Review: In light of your latest book’s concerns regarding memory, life, love, and death, it is considerably shorter than Palimp-sest, although they cover the same amount of time.

Gore Vidal: Books are as long as they are meant to be. When the subject’s done, the subject’s done. Also, my objection to most American writing is that it’s endlessly garrulous and pointless. So I thought, “Wouldn’t it be nice to be precise and to the point on what I wanted to cover?”

G&LR: You kept your observations about Howard Auster’s life and death to a discreet minimum.

GV: What would be the maximum?

G&LR: What was it about Howard that made your relationship last all of those years?

GV: No sex. But nobody believes that. This is America where everybody must have a full sex life all day long. Fifty percent of heterosexual marriages end in divorce. Where does that come from? Exclusivity. “You’re mine, you’re mine. You swore, Agnes, when I married you, that you’d be true to me.” Come off of it. This is a bunch of BS.

G&LR: You mentioned in the book that you and Howard had completely separate sexual lives. Could there be a balance between exclusivity and playing the field?

GV: I suppose that somebody sixteen or seventeen might conceive that, yeah. Reality does not support it.

G&LR: You’ve often contended that “homosexuality” is not a noun but instead a verb, an act—so one can only be a homosexualist or same-sexualist.

GV: Only a country like this one could have thought up [the idea]that sexual tastes, whatever they may be, dictate identity. Only a bunch of morons would have come to that conclusion.

G&LR: Yet, despite Kinsey’s findings, we continue with that mindset.

GV: Kinsey was not only not right about everything, he was just as puzzled as I am. He and I thought very much alike on many lines. He had come to the conclusion that sex is a continuum. It changes throughout life or doesn’t change throughout life. It’s really no big deal. So he approached it, quite correctly, as an expert on fruit flies [actually gall wasps].

G&LR: In what way can we apply this same principle to other behaviors such as religious beliefs, race, and gender?

GV: I always find that to use religion or race or sex as identification is folly. After all, once you isolate yourself in a category, Adolf Hitler will come along and say, “I don’t like this category. They’re not voting right so we better get rid of them.”

G&LR: I was just about to segue to politics. Most people from your background tend to accept, if not embrace, U.S. dominance in the world, yet you’ve always been critical of “the Empire.” Why did you turn out different from your peers?

GV: I read more books and lived a much fuller life than these people. I was brought up in the engine room of the Republic: the U.S. Senate. I know how we’re governed. I know what the weaknesses are, and I know the things we do very, very badly. One is empire building, nation building, whatever you want to call it. No, we are not suited for any great tasks as a nation. Once we have a civilization —a civilization begins by knowing the difference between an adjective and a noun—then reality starts to intrude. But as long as you go along, “Oh he’s a nice man; I trust him with everything”—this is for the barbarians. Not that we have progressed very far from that state; and we’ve done some regression of late.

G&LR: Now that the Democrats have taken over the House and Senate, what do you foresee in the final two years of the Bush-Cheney administration?

GV: It’s finished. He has the option of attacking Iran, in which case we’ll probably be blown up, since they’re rather mean and extremely competent in things such as nuclear [weapons]and so on. If he’s stopped from that, and this is a big “if,” he’ll do anything because he is a fool. It’s the first time we’ve ever had a president that I can think of who was literally a fool. He doesn’t know what he’s saying. He doesn’t understand what the words mean. “I’m a wartime president.” Well, you can’t have a wartime president without a war. Where are the wars, except the ones he starts? And he has no right to start them. He has no right to preemptively strike another country. But we had a cringing Congress, paid for by all the money on earth. The corporations quite like not having to go through the necessity of bidding [for government contracts]. Halliburton could always get first crack. There’s no reason to talk very seriously about the United States until we have developed a civilization of some kind we can all, more or less, agree on. I find that far, far away.

G&LR: Is there anything positive you can say about the Bush administration?

GV: Yes, it’s all over in a year and a half.

G&LR: Do you think it is the worst administration in U.S. history?

GV: There’s no competition. There are failed administrations. There are wrongheaded ones. There’s never been one that was disastrous to two other countries who had done us no harm and could do us no harm. There’s no example of that. And a few weeks ago, we lost habeas corpus; after 800 years, we lost the Magna Carta. We’ve got an Attorney General who I don’t think has read the Constitution. Or, if he has, he just blanks it out. To come forward with all sorts of rationalizations for getting rid of due process of law, without which there is no republic —forget democracy, we never had it and will never have it. We’re not suited for it. But we did have a very well functioning republic, which saw us through a couple of major wars, victoriously. Now we have nothing.

G&LR: In the book you mentioned the stolen U.S. elections of 2000 and 2004. Why did Gore and Kerry allow the Bush administration to steal both elections? After all, these are powerful, well-connected men, too.

GV: Powerful is not the word. Well-connected is the word—at least they knew how to raise the money. That’s well-connected in a corrupt republic. So we’re looking more and more like Paraguay. You must ask them why; I’ll never know.

G&LR: Your book deals with death quite a bit. Do you feel that the America you leave will be worse off than the one you entered in 1925?

GV: Prevailing evidence convinces me that it will be much worse. And there’s not one sociologist who will not report that upward mobility, which was always our great thing, stopped some time ago. If your father is a garage mechanic, you’re not going to make much more money than he did no matter what you do. So that is gone. We are a stagnant nation.

G&LR: Are there any current politicians you would like to see advance?

GV: Not as much as I would like to see them retreat. The system is totally rotten. How are you going to get good buds on the tree? You’re not going to. You’re going to get the dregs of Eden.

G&LR: What should we do about the inherent corruption in our system?

GV: There’s nothing to be done. It’s like asking somebody in Paraguay, “Why do you keep putting generals in office?” “Well, we put them in because they take the office.” “When are you going to stop the corruption?” “Well, when we stop having generals.” It’s circular. Our politics became totally corrupt with the invention of television and the cost of TV advertising. And the only great art form we ever created was the TV commercial. So everything’s merchandising. Anything that comes out of the Neoconservatives is going to be more lies and more hyperventilating and more and more grotesque details, because that’s all they do is lie. I think that’s what the Bushites learned—how to lie on a grand scale.

G&LR: Looking back, what is your greatest achievement?

GV: Anybody who starts to think along those lines is out of the running. I’m still running. Limping.

G&LR: What do you think about interviews in which you discuss your work—do you think it serves the work or should the work speak for itself?

GV: If you notice, I do that almost never. What have we been talking about? Politics. State of the Union. We haven’t mentioned a novel of mine. Somebody said, “Why, you could read all of Palimpsest—your first forty years—and no one would know you ever wrote a successful novel.” That’s not for me to write about. It’s rather a plus not to do that, but everyone else is braying like donkeys: “Look at me, look at me.” This is not a congenial culture, you must admit—to the extent it is a culture.

G&LR: Do you write for an audience that would discuss your works?

GV: If you think about the audience you’re writing for, you’ve had it.

G&LR: Do you write for yourself?

GV: There’s nobody else around.

G&LR: Yes, but you know others will read your novels.

GV: Well, I know they’ll get most of them wrong, but that’s the educational system. The people who write book reviews, write about the arts —the people who write about these things are nobodies. Often they’re honest enough to know that they are nobodies and they have no right to these opinions. Yes, everybody’s got the same feelings, I know that. And all feelings are equal. [But] when it comes to high culture, everybody’s not equal. Some people know more than other people. If I’m going to be instructed on brain surgery, I’m not going read Stephen King. It’s the first rule of criticism. No one but your mother cares about your opinion. Start with that. You’re a blank slate. Forget the author. He’s at least written on his slate. And you’re going to write about his writing on his slate. And you’re going to pass [judgment]: “Oh, I just hated his work. My god he’s an awful man. I can just tell.” Well, this kind of bogus moralizing goes on. We haven’t had a decent literary critic in my lifetime. We’ve had good critics who bury themselves in the academy and are never seen again, particularly by their students. We occasionally have great explainers like Edmund Wilson, who stopped reviewing novels around 1945. Just when my generation really needed a critic, he’s doing the Iroquois Indians—which is probably far more useful. So we are adrift. Even the worst newspaper in England has better book reviewers than The New York Times. So don’t pass judgment. Now, what do you do if you have to review a book? The most difficult thing on earth, and most people don’t know how difficult it is, because most people can’t do it: describe what it was that you read. If you do that properly you don’t have to throw adjectives around and make cute noises. Just describe it. The words that you use for the description will lead the criticism. Now if you can plow that into some heads, you will have done great work.

G&LR: What current novelists do you admire?

GV: Everybody thinks old novelists go rushing out to get the latest product, to see what the latest models are. I just don’t read them. I’ve never read contemporary fiction unless I realized it was of a very high order, which was not often. But how could you tell? Look at book reviewing. It’s an absurdity. A good review means nothing. A bad reviewer is somebody who feels he’s been cheated and is due by this hustler who’s got ahead of him in line.

G&LR: Have there ever been criticisms that hurt your feelings professionally?

GV: No. What I hate is being misquoted.

G&LR: Robert Altman recently died at the age of 81. As someone of his age and an ardent filmgoer, what do you think of him and his films?

GV: I had dinner with him two nights before [his death]in New York. I trust it was not cause and effect. He was wonderful. His films are great. I’ve never seen a bad one. I’ve seen ones that were not as good as others.

G&LR: You write about power and privilege from what many would perceive as a powerful and privileged viewpoint or position in life.

GV: Well, you write what you know. As Iago says to Othello, who asks why, “You know what you know.” One of the great mysteries of Shakespeare, that line.