IN Transliberation: Beyond Pink or Blue (1998), the late writer-activist Leslie Feinberg, who preferred the gender-neutral pronouns hir and ze, described hirself as “a masculine feminine”: “I do not identify as a male, so I don’t believe that I should have to change my body to ‘match’ my gender expression so that authorities can feel comfortable. … Being a masculine female means I am uni-gendered, not bi-gendered.”  Feinberg, who died at the age of 65 in Syracuse, New York, on November 15, 2014, really just wanted to be Les Feinberg. Hir spouse, the poet Minnie Bruce Pratt, who stated that Feinberg was the “first theorist to advance a Marxist concept of ‘transgender liberation,’” died of complications from multiple tick-borne co-infections, including Lyme disease. Earlier in hir life, Feinberg had been near death from endocarditis, an infection of the heart valves. Transphobic health care providers offered only contempt, and the condition was left untreated for too long, leading to other medical problems.

Feinberg, who died at the age of 65 in Syracuse, New York, on November 15, 2014, really just wanted to be Les Feinberg. Hir spouse, the poet Minnie Bruce Pratt, who stated that Feinberg was the “first theorist to advance a Marxist concept of ‘transgender liberation,’” died of complications from multiple tick-borne co-infections, including Lyme disease. Earlier in hir life, Feinberg had been near death from endocarditis, an infection of the heart valves. Transphobic health care providers offered only contempt, and the condition was left untreated for too long, leading to other medical problems.

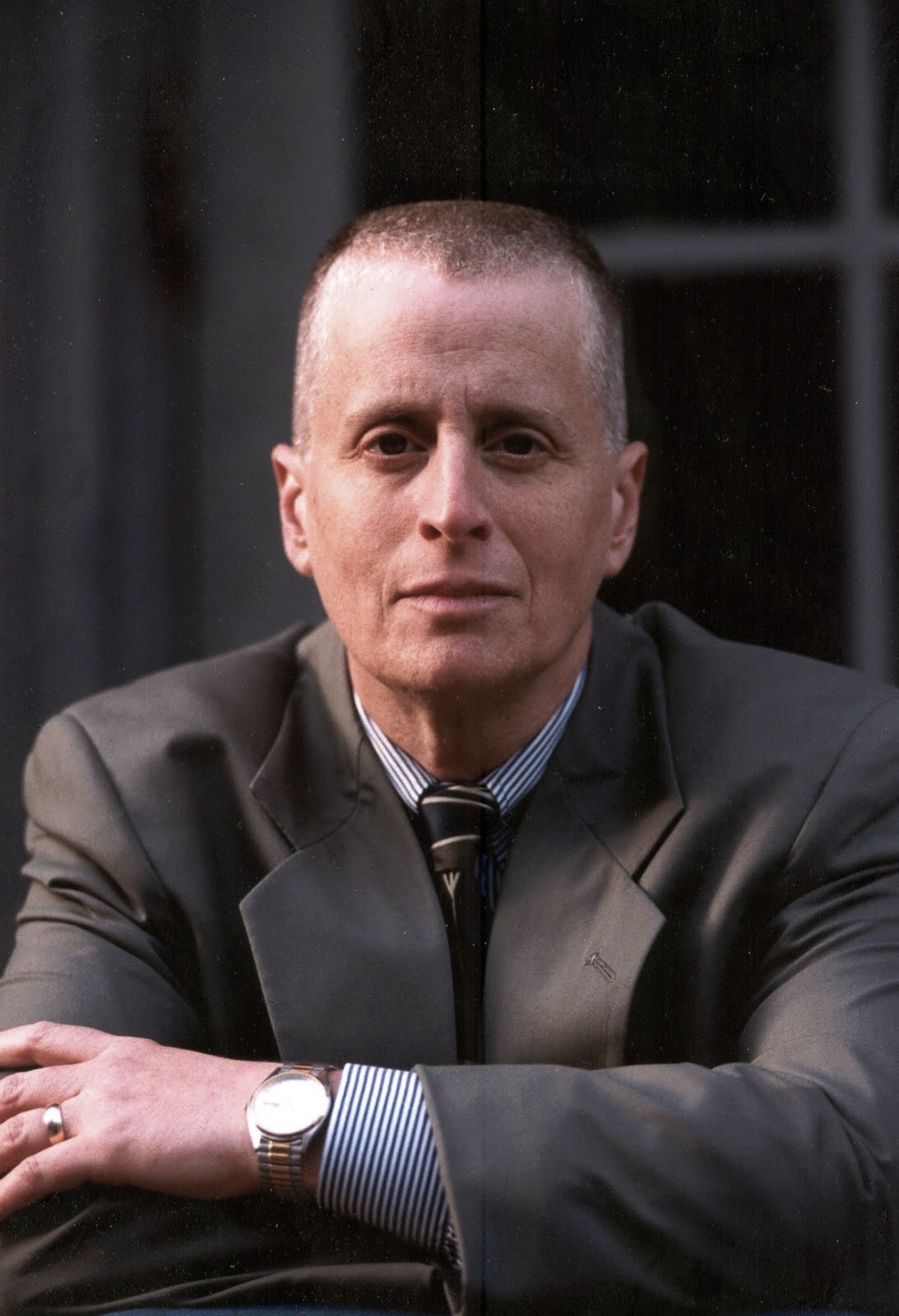

Born Diane Leslie Feinberg in Kansas City, Missouri, ze recounted a few anecdotes of hir childhood in Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman (1996), a well-researched history of transgender people through history and across cultures. Transgender Warriors includes a slightly blurred photo of Feinberg, around age seven, looking as forlorn and hopeless as any child in a war-torn country. The family later moved to Buffalo, the setting for part of Stone Butch Blues (1993), Feinberg’s first published and best-known book. In this semi-autobiographical novel, butch lesbian Jess Goldberg tells the story of growing up in Buffalo in the 1950s and running away at the age of sixteen. Feinberg goes into chilling detail about police brutality that butches, femmes and drag queens faced when captured in bar raids. In the 1960s, Jess decided that she “can’t survive as a he-she much longer” and decided to start taking male hormones to “pass as a guy.”

In 1994, Stone Butch Blues, which was reviewed in the in the Fall 1994 issue of this magazine, won the American Library Association’s (ALA) Gay and Lesbian Book Award (now known as the Stonewall Book Award), as well as the Lambda Book Award for lesbian fiction. One member of the ALA awards jury vividly recalls a celebratory dinner on Ocean Drive in South Beach. This group of librarians had been waiting half an hour for Feinberg to show up, and finally the author arrived, breathless, direct from the airport, where ze had flown in from New York after speaking at a twenty-fifth anniversary commemoration of the Stonewall Riots. Feinberg, who was a powerful, dynamic speaker, had a deep and unwavering love of libraries and the librarians who helped give voice to the powerless.

Drag King Dreams, Feinberg’s second novel, was published in 2006 and was reviewed in the September–October 2006 issue of this magazine. Set in the days just after 9/11, it is narrated by Max Rabinowitz, a butch lesbian, and is populated by Max’s friends: drag queens and kings, immigrants falsely accused of terrorism, and unlikely friendships that arose among them all. Through political activism, Max—who works off the books as a bouncer in an East Village drag bar—is able to find hope for the future.

As a young adult, Feinberg fell in with congenial people who happened to be communists and became involved in Workers World, an American Marxist-Leninist party that, since 1959, has protested against racism, sexism, war, and imperialism. Feinberg became managing editor of Workers World newspaper, a position ze held for many years, and wrote a 120-part series from 2004 to 2008 exploring the links between socialism and LGBT history and politics. Hir last book, Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba (2009), is a collection of 25 essays that originally appeared as a series of articles, “Lavender & Red,” in Workers World.

Author’s Note: Thanks to John DeSantis for his assistance in preparing this article.