J. C. LEYENDECKER (1874–1951) was an artist of many firsts. With his illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post, he can be said to have invented what the modern magazine cover should look like. He was one of the first popular artists to achieve a kind of greatness, and, as the most widely seen image-maker of his era, he defined the look of the fashionable American male during the first few decades of the 20th century. As a gay man himself, he did all this while introducing a subtly homoerotic subtext into many of his drawings, thereby prying open a crack in the closet door of his era.

In spite of his extraordinary achievements, his name nearly vanished after he died in 1951. Seven decades later, an exhibition at the New-York Historical Society titled Under Cover: J. C. Leyendecker and American Masculinity [reviewed here in the May-June 2023 issue]turned a spotlight on his work when it opened last May, providing a forum for conflicting viewpoints about Leyendecker’s art and life.

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was born in Montabaur, Germany, in 1874, and emigrated to Chicago with his family when he was eight years old. He showed a precocious talent for drawing, studying at the famous Art Institute of Chicago when he was only fifteen. Such was his ability that his teachers encouraged him to study in Paris, which was the mecca for serious artists at this time. As luck would have it, his brother Frank (1876–1924) was also a talented artist—nearly as good but not as disciplined as Joseph. Together they traveled to Paris in 1896, where they enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian, which was headed by the influential William-Adolphe Bouguereau. At this point in their lives, the two brothers were as thick as thieves, but their lives were destined to diverge.

The classical training that Joseph received in Paris strongly shaped his approach to art. His teachers, who looked down on “commercial” artists, made him copy the Old Masters. However, as soon as he hit the Paris boulevards, he found himself surrounded by the publicity posters of artists like Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha, whom he admired and befriended. These artists believed in a revolutionary idea that challenged the art establishment: Great art could be produced for visionary companies that manufacture products for the masses. Inspired by this manifesto, Leyendecker won a contest for the cover of the magazine The Century with an image clearly influenced by Mucha. The cover was so popular that it was sold as a poster, something unheard of at the time. The realization that he could make money and get famous by creating art for the masses, not just for wealthy patrons, stirred his imagination. This trend had yet to reach the U.S., and he saw an opportunity back home, so he and his brother Frank returned to Chicago and opened a studio.

J. C. Leyendecker became a full-time illustrator, creating images for advertising that fulfilled the radical ideal that he’d learned in Paris: “My illustrations introduce art into the details of everyday life, refining and improving them,” he declared. It wasn’t long before he created his first cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, in 1899. His innovative contract allowed the Post only a one-time use of a given illustration, with rights returning to the artist after publication. It was an arrangement that he insisted upon for his whole career.

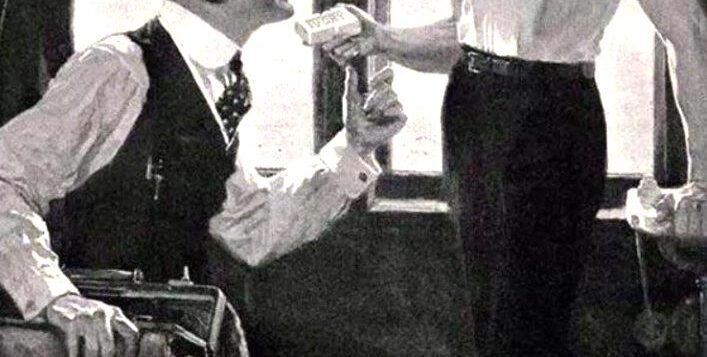

Leyendecker understood that, just as an advertisement has only a split second to catch a potential buyer’s interest, a magazine cover had to communicate an idea instantly, without explanatory text. He achieved both goals with a unique style that was immediately recognizable. Previously male fashion ads were static, its models looking like cut-out dolls. He created a technique for advertising with exaggerated brushstrokes and vibrant colors that grabbed the viewer’s interest with their lifelike, and beautiful, male models. He had burst onto the scene at the perfect time. The “Roaring Twenties” were overturning the remnants of Victorianism, launching a new focus on lifestyles and fashion statements that’s still with us today. Madison Avenue realized that it could cajole consumers into new buying habits with images like the ones that Leyendecker was producing. This is where the story starts to get interesting. Leyendecker found a way to create ads for mainstream American buyers that contained a homoerotic subtext that’s quite apparent to our modern eyes. For instance, his ads for Ivory Soap feature naked soldiers and men checking each other out in the showers. Nor does the copy for these ads attempt to deflect their homoerotic imagery. A 1920 ad showing an ambiguous male encounter on a train features a tantalizing exchange. “There is no other soap that satisfies me now,” one man says. Responds the other: “It’s surprising how many of the traveling men I know carry it too.” The model in another Ivory Soap ad sports what seems to be an erection [at left]. It was Whoopi Goldberg who made the owner of this painting aware of this detail. Since then, the owner has admitted that she can’t see anything else in the picture. Leyendecker was soon inundated with commissions, many of which he would pass on to Frank, who got tired of living in his brother’s shadow. Their destinies changed forever on a fateful day in 1903 when Frank welcomed into the studio a gorgeous Canadian, Charles Beach (1881–1954), who was offering his services as a model. Frank immediately recommended Beach to Joseph, who was blown away by Beach’s beauty and by his skill as a model, never talking or needing to rest. (Leyendecker avoided working from photographs, using live models such as actors John Barrymore and Fredric March, whom he coached to express emotions as a movie director would.) It was a case of opposites attracting. Leyendecker was 29, short, painfully shy, and given to stuttering. Charles was 22, 6-foot-2, and described as “powerfully built and extraordinarily handsome—like an Ivy League athlete, with impeccable manners and always beautifully dressed.” This was the beginning of a fifty-year partnership that would shape both of their lives and careers. Beach became Leyendecker’s manager, negotiating higher prices for his work and helping him to make the transition from a commercial illustrator to a celebrated artist. Meanwhile, Joseph Leyendecker monopolized Beach as a model, which was a source of tension between the two brothers. When their father died in 1916, Beach moved into the family mansion in New Rochelle, replacing the brothers’ older sister Mary Augusta as the family caretaker. She continued to manage Frank’s career but resented being replaced as Joseph’s confidante. Beach posed for sports pictures that college boys would put up in their rooms, and also for patriotic scenes of hunky sailors working with phallic projectiles or, in one case, as the model for Lady Liberty on a poster for “Liberty Bonds.” Their big break came in 1905 when Cluett Peabody & Co. accepted Leyendecker’s pitch to create an icon for their detachable shirt collars: “Not simply a handsome and manly man but the ideal American man, the Arrow Collar Man.” Beach posed for these ads, and the Arrow Collar Man was born: handsome, preppy, and athletic, with a desirable body underneath his clothing, exceptional poise, a chiseled face, and a chin that conveyed confidence and determination. It was this image that in many ways defined not only male fashion trends of his era but an image of a new, confident America. The Arrow Collar Man, the first systematic branding campaign in U.S. history, caught lightning in a bottle by leading the common man to believe that buying these inexpensive collars and shirts would give him an air of civility and wealth. This alchemy between Beach’s looks and charm and Leyendecker’s artistry turned the Arrow Collar Man into a bona fide sex symbol. Beach received more fan mail than movie star Rudolph Valentino. Arrow Collar received some 17,000 letters, many containing marriage proposals, in just one month. Little did Beach’s fans realize that their ideal man was the partner of the artist, who had turned him into a superstar. The Arrow Collar Man became a phenomenon, inspiring popular songs and a Broadway musical, and changing how the clothing industry marketed itself. Arrow Collar cornered 96 percent of the market, destroying its competition with sales of over $32 million in 1918. Leyendecker’s illustrations embodied the elegance of the Great Gatsby era even before Fitzgerald’s novel was published in 1925. When Daisy tells Gatsby, “You always look so cool, like the advertisement of the man,” she must be referring to the Arrow Collar Man. Leyendecker was arguably the most famous artist in America, and Beach’s likeness was so familiar that strangers stopped him in the street. Their movie star lives, with lavish parties at their mansion, personified the Gatsby themes: the lure of the American dream and its symbols of wealth and style, starting with a well-pressed shirt. When gossip columnist Walter Winchell reported on these parties, he never mentioned the hosts’ relationship, probably for fear that he would no longer be invited to these coveted events. However, there were clouds on the horizon. In 1923, Frank and Mary Augusta moved out of the family home after a huge fight with Leyendecker and Beach, leaving them alone and, more importantly, unable to conceal the nature of their relationship. It was around this time when, worried that rumors would destroy their career, Leyendecker tried to set up an arranged marriage with one of his favorite female models, Phyllis Frederic. Despite Beach’s opposition, he asked Phyllis’ father for her hand and even provided a business plan. Her father refused, citing their over thirty-year age difference. This setback didn’t faze the artist, who continued to create ads depicting men gazing longingly at each other—in one case, while admiring a phallic golf club; in another, while one man offers his glove to another, suggesting a proposal of some kind. While many believe that Leyendecker’s work “subverted heterosexual imagery,” his ads reflected the relatively relaxed attitudes of this era (the “Roaring Twenties”). Society permitted and encouraged men to engage in homosocial interaction in spaces such as fraternity houses, locker rooms, sporting events, and men’s clubs, which facilitated male bonding and rituals with a degree of physical and emotional intimacy that is generally out of bounds even today. These were the all-male environments that provided the backdrop for much of Leyendecker’s work. No one questioned these scenes because they simply reflected the reality of male behavior and were consistent with American norms, notwithstanding the sly glances and suggestive poses of some of the men in these depictions. The success of Arrow Collar prompted other men’s companies, such as Kuppenheimer and Interwoven Socks, to hire Leyendecker as well. The ads he produced could only hint at a subculture that was burgeoning in cities like New York. His “metrosexual” men (as we would say), such as the languid males caressing their sheer stockings in Interwoven ads, offered a glimpse into a fashion world that echoed the dandy culture of Oscar Wilde’s time. These men flouted the sexual and gender protocols of mainstream society with flamboyant styles of clothing, mannerisms, and conversation, presenting these affectations as signs of upper-class sophistication. George Chauncey described this dynamic in Gay New York (1994): “The effeminate ‘fairy’ was so visible in New York that it came to represent all homosexuals in the public mind,” blinding people to the true persona of the “refined metrosexuals” depicted by Leyendecker. A contemporary artist, Charles Demuth (1883–1935), portrayed this subculture in sexually provocative watercolors that he was unable to exhibit during his lifetime. In contrast, Leyendecker’s ads portrayed a social world in vaguely homoerotic ads that showcased ambiguous relationships between unambiguously masculine men. An ad for Gillette featured an older and a younger man sharing an intimate bathroom space. Are they father and son, or a “daddy” with his younger lover? The meaning of the scene was in the eye of the beholder. This strategy worked like magic. Women were attracted to these men, men wanted to be like them, and gay men picked up on the intimacy and sexual tension, projecting their own desires into these scenarios.

WHILE LEYENDECKER was helping to shape the zeitgeist, he also reimagined the American magazine with his covers for The Saturday Evening Post, turning it into the main venue for mass market brands to sell a lifestyle to the American public. When he was hired in 1899, magazine covers featured an illustration from a story in that issue. Leyendecker’s approach was to create a stand-alone image that grabbed the browser’s interest and sold magazines. His covers for holidays such as Easter, the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, and Christmas became an event, even shaping the way in which they were celebrated. For instance, the 1914 Mother’s Day cover is what launched the tradition of giving flowers to Mom. Whenever one of his covers appeared—there were 322 all told—the Post’s circulation would receive a bounce, until it became the most popular magazine in the world, with over two million readers and annual ad revenue of $28 million. Leyendecker was soon earning $50,000 a year—nearly a million dollars in today’s currency. It’s fascinating that it took a gay immigrant without a high school education, someone who knew how hard it was to be accepted, to create the images that American men aspired to emulate. Many of these covers used Beach as the model, and, even though the magazine was conservative and family-oriented, many featured what look to us like sexualized queer images. Two striking examples are his 1932 image of the U.S. Olympic Eight and his iconic Lifeguard, the sex symbol of this era, who’s wearing a skintight bathing suit while ignoring the female bathers who are trying to get his attention. When talking about Leyendecker and The Saturday Evening Post, we can’t avoid discussing his complicated relationship with Norman Rockwell, America’s even more famous illustrator. Rockwell went from being Leyendecker’s admirer to being his friend and protégé and eventually his rival, ultimately replacing Leyendecker at the Post. Rockwell devoted a chapter of his autobiography to Leyendecker. As the latter was very private, this chapter has become a key source of information about him. But the chapter is very biased and of questionable reliability. For example, Rockwell states that “Leyendecker could never paint a woman with any sympathy,” an assertion that doesn’t hold up to scrutiny and seems to be a veiled attack on Leyendecker’s sexuality. When he accuses Beach of being a parasite who cut Leyendecker off from everyone else, he was probably resentful of Beach’s closeness to Leyendecker and his own estrangement from his onetime mentor. Rockwell’s style was so similar to Leyendecker’s that Post readers had a hard time telling them apart. Their approach, however, was quite different. Rockwell’s illustrations tended to tell a story, while Leyendecker was more interested in style and composition than in establishing a clear narrative. This is why we’re still wondering about the true meaning of his art a century later. The contrast can be found, for example in the two artists’ representations of the Thanksgiving holiday. Rockwell’s famous Freedom from Want shows a celebration of a traditional family holiday. In Leyendecker’s cover, two square-jawed, all-American icons, a Puritan and a football player, are standing side-by-side and seem to occupy separate worlds, even as they appear to be checking each other out. Leyendecker painted his last cover for the Post in 1943. When the commissions stopped pouring in, he and Beach had to let the house staff go, and they became semi-reclusive. On July 25, 1951, Leyendecker died of a heart attack in Beach’s arms. He left half of his estate to his sister and the other half, the equivalent of nearly half a million dollars today, to Beach, who was described in Leyendecker’s obituaries as friend, model, secretary, or aide, but never as his life partner. Beach stated in his final interview: “I stuck with the Boss for 49 years. He is gone and now I am a ship without a rudder.” Leyendecker had asked Beach to destroy all of his work. Beach ultimately reconsidered, hosting a yard sale at their home in which sketches and finished work sold for a pittance. They are now worth thousands of dollars. After Beach died, Leyendecker’s reputation began to fade. His timeless illustrations, however, are being rediscovered and his reputation rehabilitated. When Ralph Lauren opened a flagship store in New York, they used Leyendecker-style advertising. We’ll never know to what extent Leyendecker deliberately encoded his images with homoerotic desire. What’s undeniable is that his pioneering ads planted the seeds for today’s gay-specific and lifestyle ads from brands such as Calvin Klein and Abercrombie & Fitch. Ultimately, his work proves that the homoerotic imagination has been a key part of American consumer culture since its origins well over a century ago.

Ignacio Darnaude is an art scholar, lecturer, and film producer. He is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight: Breaking the Queer Code in Art.

Discussion1 Comment

There’s an amazing trove of Leyendecker’s work in Stockton, California (of all places), at the Haggin Museum, which also has a great collection of art and historical artifacts. And the museum texts are quite open about his sexuality. Worth a day-trip from the San Francisco Bay Area. Web site is hagginmuseum.org.