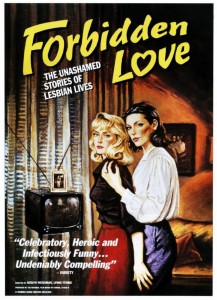

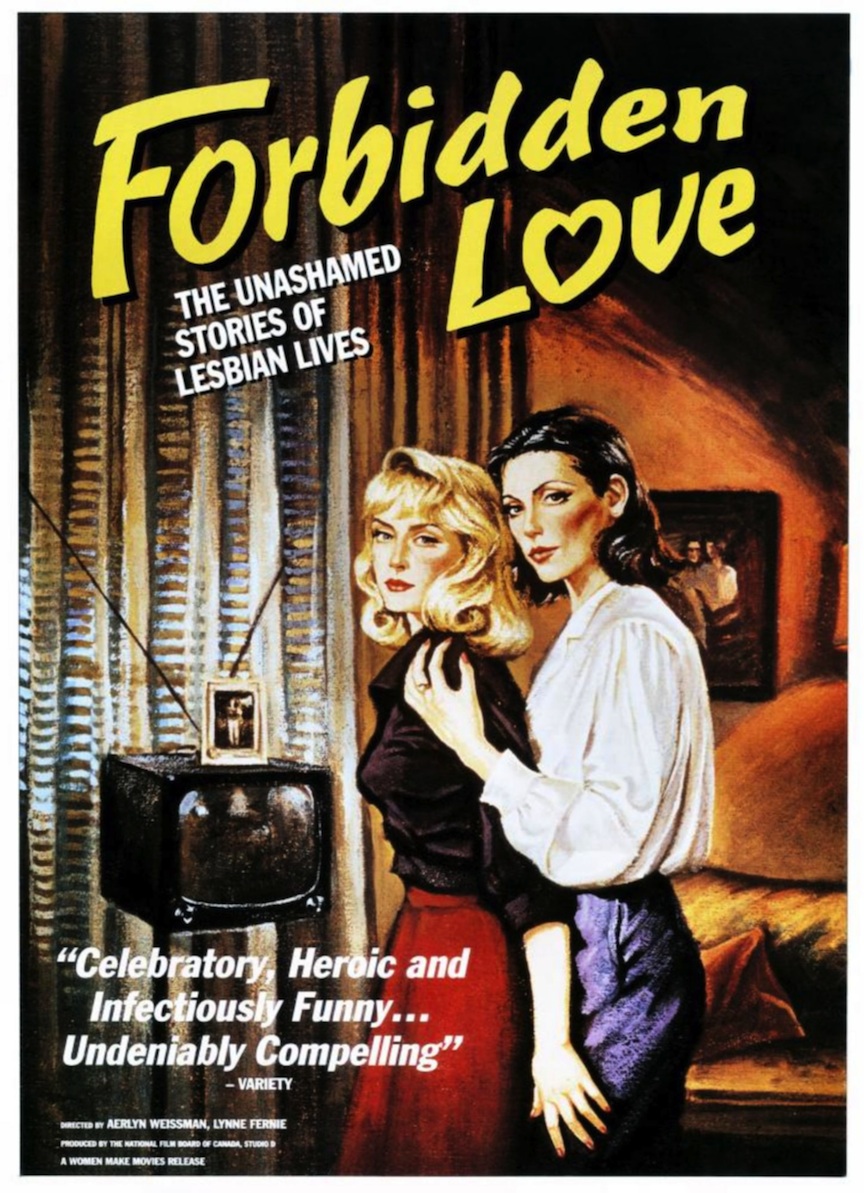

I’LL NEVER forget the first time I saw Forbidden Love: The Unashamed Stories of Lesbian Lives. It was the fall of 1992, and the documentary was premiering at  Image+Nation, Montreal’s queer film festival. Four years in the making, Forbidden Love featured interviews with a number of older lesbians from across Canada, each telling her own story about how she lived as a lesbian through a much more conservative era, roughly the 1940s through the ’70s.

Image+Nation, Montreal’s queer film festival. Four years in the making, Forbidden Love featured interviews with a number of older lesbians from across Canada, each telling her own story about how she lived as a lesbian through a much more conservative era, roughly the 1940s through the ’70s.

The women in the film are all smart, intriguing, brave, and above all funny, and their stories are full of revelations large and small. Their sense of humor was clearly part of their survival strategy in the bad old days. They speak of leaving bad marriages to take the risk of finding “lavender” love. They describe raids on lesbian bars by police. They recall unforgiving parents and co-workers.

But for all the hardship they describe, filmmakers Lynne Fernie and Aerlyn Weissman managed to make a movie that was beautifully uplifting. When I saw the film in 1992, the audience of about 1,000 gave it a standing ovation that lasted for many minutes. Since then, I’ve screened Forbidden Love at each and every opportunity I could as a university instructor, as a generation of younger cineastes have no idea it even exists. Sadly, for the past fifteen years Forbidden Love has been out of circulation due to various copyright expirations. But that’s about to change: Canada’s National Film Board (the NFB, which produced the film) has spent the hard cash needed to renew the necessary copyrights, and Forbidden Love is again out on DVD.

Forbidden Love is not striking only for its content but also for its formal originality and ingenuity. Interwoven with the women’s testimonials are a series of fictional vignettes performed by two actresses, based on the pulp lesbian fiction of the day. At the end of each vignette the actresses look directly into the camera, creating what could be a pulp fiction novel cover. They also take some liberties with the pulp novels they enact, allowing their heroines a happy ending. How’s that for radical filmmaking?

Weissman says a big part of their strategy was to avoid playing the victim. “When you’re making a film, you’ve got to think about where the focus is,” she told me from her Vancouver home. “The victimization? The resistance? I personally always took issue with the idea that I was marginal. I wasn’t marginal; I was in the middle of things. For many people in the queer community and many of the women in Forbidden Love for example, their resistance is characterized by a remarkable sense of humor and irony, that sense of the disjunction between the way our institutions say things should be and the reality on the ground, which they know in their own lives is so different than the hetero norm.” Justifying the use of humor in the film she observed that “resistance is not mean-spirited; it is not stupid; it is smart and funny. Laughter in some sense is the best revenge.”

The filmmakers’ archival research led them to understand how homosexuality had been seen and categorized historically. “The NFB library didn’t have the categories ‘gay’ or ‘lesbian’ or ‘homosexual,’” noted Fernie. “You had to look under ‘crime’ and ‘police’ because it was only covered under deviance or criminal activity.” Added Weissman: “This led us to be more adamant about having the word ‘lesbian’ in the subtitle. We were so out and in your face about it. This is something we learned from Jane Rule: you have to put ‘lesbian’ in the title or it will be buried.”

As exhilarating as Forbidden Love is for queer audiences, it has had huge mainstream success, winning the Genie (the Canadian equivalent of the Oscar) for Best Documentary. “As much as the film might be empowering for a community group,” said Fernie, “it also inserts a missing component of Canadian history, and it shows in the fact that it had crossover success, playing at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) and other mainstream festivals, and being broadcast on CBC [Canada’s national TV network], PBS, and other mainstream broadcasters.”

When I think back to that Montreal screening in 1992, I can’t help remembering what I was experiencing as a gay man. It was the worst of times for gay men, when AIDS was being referred to as a holocaust by Larry Kramer and there were no life-saving drugs in sight. The other landmark film premiering at that year’s festival was The Living End, Gregg Araki’s brilliant meditation on living with HIV in the U.S., a feature understandably soaked in grief and anger.

Fernie and Weissman concede that having the film in legal limbo was agonizing, and they’re grateful and relieved that it’s set to be re-released. “It was a funny feeling,” Fernie told me, “because we worked so hard to allow those women to tell their stories of liberation on the big screen. And then, for quite some time, it felt like they had been silenced again. Now most of the women in the film have passed away, of course. But it kind of felt like we were liberating them all over again.”

Discussion1 Comment

I’m delighted to learn that this wonderful documentary film will finally be available on DVD. It might be of interest to your readers to know that the two actresses providing scenes between the interviews were based on my characters, Beth and Laura, from my series of pulp novels, “The Beebo Brinker Chronicles.” I was invited by producers Lynn Fernie and Aerlyn Weissman to participate in “Forbidden Love” as the author of some of the well-known lesbian pulps from the era. Just a year ago, Aerlyn Weissman and I appeared together, along with a few of the surviving women featured in the film, at Pat Hogan’s Bold Fest in Vancouver, B.C. At the time, Aerlyn despaired of getting “Forbidden Love” out on DVD because of the cost of the copyrights on music used in the film. So it’s a pleasure to see that that hurdle was finally overcome. And it’s certainly heartening to know that people have so enjoyed and valued this bit of our history. Perhaps now more of them will be able to appreciate it. Please sign me Ann Bannon