James Merrill: Life and Art

James Merrill: Life and Art

by Langdon Hammer

Knopf. 912 pages, $40.

JAMES MERRILL (1926-1995) was that rare breed: a 20th-century poet who had money. His father had founded Merrill Lynch and provided a lifelong income for his son. Merrill had extraordinary talent too, and, if this marvelous, comprehensive critical biography showcases every jewel of social incident, glamour, fame, travel, and sexual adventure, it also brings home the sheer size of Merrill’s poetic achievement—and also, on occasion, comparable ones in prose and drama. Merrill published two ludic but charming novels, The Seraglio (1957) and The (Diblos) Notebook (1965), and, near the end of his life, a memoir titled A Different Person (1993).

But Merrill was a born poet: driven, as he insisted, to “make song” out of the otherwise senseless “empty hive” of the poet’s day-to-day existence; to make sense of stasis; to make good of loss; above all, to make meaning out of chaos.

The contrast between Merrill and the emerging Beat movement, or rock-and-roll music, or the arrival of the teenage rebel in the 1950s, could not have been greater. Later, there would be fellow travelers, such as Thom Gunn, but Merrill’s cool, inexpressive qualities, while securing critical recognition, struck many reviewers as aloof, or too knowing, or obscure. Writing verse was a desk job for Merrill, requiring specific tools—in particular, a rhyming dictionary—and mental aptitude. Though he did read his own verse in public, he could never have “performed” it à la Allen Ginsberg. Nor was there a “personality” which it contrived to impose on the reader. When asked once if he longed for a wider readership, Merrill recoiled: “Think what one has to do to get a mass audience. I’d rather have one perfect reader.”

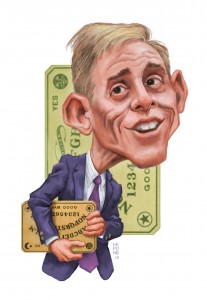

The second part of Merrill’s career saw not so much a reversal of direction as a sharp tangent. The three volumes that came to constitute The Changing Light at Sandover—The Book of Ephraim (1976), Mirabell: Books of Number (1978), and Scripts for the Pageant (1980)—emerged out of Merrill’s consultation, along with his partner of four decades, David Jackson, of otherworldly spirits during Ouija sessions that they hosted. The deployment of messages from beyond allowed Merrill a thematic and dramatic freedom that would extend across more than 17,000 lines. This was still poetry, but apparently written at the behest of forces outside of the author. Just as the “different voices” in The Waste Land had liberated T. S. Eliot, the spirits in Merrill’s work structure, offer commentary on, and render coherent, the three parts of his epic. Liberated from any mortal coil, they speak freely, wittily, bitchily, irreverently. The poet himself could select, while not being seen to select, from among the voices of the deceased. One recurrent voice is that of the recently deceased English poet W. H. Auden. Wallace Stevens also intrudes. But Merrill also ventriloquized close friends who had died, plus larger figures such as archangels and prophets. The result is a sustained, idiosyncratic, visionary poetic universe—a “homemade cosmology as dense as Blake’s,” as one critic recently put it; an “occult splendor” in Harold Bloom’s succinct summary.

Sandover remains Merrill’s outstanding achievement, its breadth and porousness allowing it to seem paradoxically replete: a sort of achieved, personal mythos. At the same time, its eclectic cultural, social, personal and even political allusions seem consonant with prose experimentation we might describe as “postmodern”; Samuel Beckett is a key touchstone here. Above all, its apocalyptic thrust came to articulate, uncannily early, the growing concerns of an American, and also a global population, sensing the slow senescence of Planet Earth, ravaged and terminally endangered by its exploitative occupants and their mindless material pursuits.

porousness allowing it to seem paradoxically replete: a sort of achieved, personal mythos. At the same time, its eclectic cultural, social, personal and even political allusions seem consonant with prose experimentation we might describe as “postmodern”; Samuel Beckett is a key touchstone here. Above all, its apocalyptic thrust came to articulate, uncannily early, the growing concerns of an American, and also a global population, sensing the slow senescence of Planet Earth, ravaged and terminally endangered by its exploitative occupants and their mindless material pursuits.

Among the longest and most challenging of literary epics in any language, Sandover continues to beguile and challenge readers precisely because of its arcane references and its elliptical and obscure qualities. In life, Merrill was contrastingly immediate and direct. He and Jackson may have traveled frequently, but wherever they settled, they lived modestly. They made their American home in the unlikely redoubt of Stonington, Connecticut, far from any metropolis. For over a quarter century they spent winters in Athens, where both partners had recourse to a succession of Greek gigolos, party boys, and soldiers, as well as a series of more serious lovers. Merrill relished witnessing the real hardship and life choices facing those with uncertain careers, limited income, and changeable circumstances. He never consorted with the social elites.

Reflecting on his pampered upbringing in an interview with fellow poet J. D. McClatchy, Merrill recalled how, unlike the members of his family, their servants had “lives [that]seemed by contrast to make such perfect sense. The gardeners had their hands in the earth. The cook was dredging things with flour, making pies. My father was merely making money, while my mother wrote names on place-cards, planned menus, and did her needlepoint.” Later, when Key West came to replace Athens as the couple’s second home, they lived equally frugally, entertaining and being entertained by other writers, artists, and academics—among them Alison Lurie, whose memoir of their friendship, Familiar Spirits (2002), provides an animated complement to Hammer’s biography.

One thing Lurie could never quite do, perhaps, was explain fully the Merrill-Jackson bond. The couple tired of one another but stayed together. For Merrill, this seems to have stemmed from a personal ethic: this was loyalty, plain and simple. For Jackson, it was perhaps more materially circumscribed. An aspiring novelist when he and Merrill first met in 1953, Jackson found himself invariably blocked. Still worse, when he did write, the results struck both himself and Merrill as mediocre. He turned to painting, interior design, decoration, hosting, and entertaining by turns, all without particular distinction. But in his prime (before his drinking took hold), Jackson was evidently a stabilizing influence on his partner, and also a great social force. He seems brasher than Merrill, someone who allowed the poet to adopt the reflective, responsive, if still gregarious role he needed to create.

Other lovers and friends continued to appear in Merrill’s shorter verse, which retained a highly distinctive lyricism while vaguely echoing the subtle and allusive homoerotics of some of Auden’s verse, or indeed much of Constantine Cavafy’s. Merrill ruminated on the allure of beauty, but just as much on the pull of intellectual ideas, belief systems, word play, number games, and the logical cut-and-thrust of intellectual debate. His last two volumes, The Inner Room (1988) and A Scattering of Salts (1995), offered a set of codas to the expansiveness of Sandover. Mortality, physical decline, and the transience of worldly pleasure loom large. Although Merrill never declared it publicly, he knew he was HIV-positive, and his health saw consequent acute peaks and troughs. Key friends he lost and elegized included David Kalstone, the critic who first, and perhaps best, recognized Merrill’s gifts, placing him among American poets like Elizabeth Bishop (also a friend), Robert Lowell, Adrienne Rich, and John Ashbery. Hammer, in contrast, emphasizes Merrill’s closeness to Wallace Stevens, also from Connecticut, and likewise a formalist poet dedicated to the elusive significance of the quotidian.

Merrill experienced his difficult final years—estranged from Jackson, increasingly reclusive in Key West—pursuing relationships with a succession of improbable candidates, including, over the last decade or so, the actor Peter Hooten, who had played the Marvel Comics character Dr. Strange in a TV movie and who collaborated with Merrill on a misconceived film version of a stage adaptation of Merrill’s great work, Voices from Sandover (1990). The poet was increasingly feted, within and beyond academe, after he won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for the 1976 volume Divine Comedies, in which the first part of the Sandover trilogy appeared.

Merrill would have enjoyed the coincidence that Hammer’s first mention of AIDS occurs on page 666. As with all AIDS-related declines, the bare constituent elements of Merrill’s desperation, stoicism, resignation, and self-concern make for a progressively grueling read. He nonetheless completed A Different Person (1993) and ensured its publication in the face of outright hostility from his mother Hellen, who would outlive her son, and whose embrace of his creative gifts was marked by a refusal to confront or discuss his sexuality.

Hammer has done a wonderful service, mining every conceivable archive for this mammoth undertaking, but also tracking down as many of Merrill’s peers, friends, and lovers as are now to be found. Hammer comments that his subject “enjoyed people, and needed lots of them. His friends were arranged around him like an opera cast: the principals, supporting singers, fabled stars with cameos, comic relief, an ingénue or two, and the full chorus behind.” A Yale English professor, Hammer is also a fine critic who is notably sensitive to the particularity of Merrill’s allusions, his choice of symbolism, and his selection of experience.

The novelist Allan Gurganus told Hammer that Merrill’s privileged background paradoxically gave him the opportunity to measure out and improvise a very different, non-material way of living, and to find new ways of writing out of that lifestyle: “He approached life as an experiment. It was a possibility, not just an entitlement.” Merrill’s embrace of constrained form gave service by binding securely the free, chaotic, unpredictable, and even sometimes dissolute life he made his own, and for so long shared with Jackson. Auden once defined poetry as “memorable speech,” a turn of phrase that nicely reflects his own and Merrill’s achievements. Hammer has succeeded in illuminating Merrill’s indisputable legacy as one of America’s most important postwar poets through this adept and memorable biography.

Richard Canning is completing a biography of English novelist Ronald Firbank, having brought out an edition of Firbank’s Vainglory in 2012 (Penguin Classics).