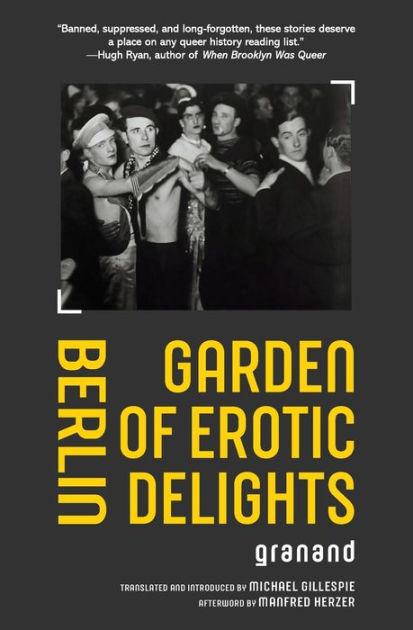

BERLIN GARDEN OF EROTIC DELIGHTS

BERLIN GARDEN OF EROTIC DELIGHTS

by Granand (Erwin Ritter von Busse)

Translated by Michael Gillespie

Warbler Press. 106 pages, $10.95

IN “NOCTURNE,” one of five short stories in this slim collection, a young man named Freddy is lying in bed when a burglar breaks into the room. They talk, and one thing leads to—well, to sex, obviously, because we’ve seen this porn set-up countless times. In this particular version, the sex is not explicitly shown, but it definitely happens, and joyously so—which is remarkable, as the story was published over 100 years ago, in 1920.

Berlin Garden of Erotic Delights (the original title was Erotische Komödiengärtlein) was written by Granand, the pseudonym for Erwin Ritter von Busse (1885–1939), a painter, writer, and theater director who, among other things, worked with Max Reinhardt in Berlin.

Even if the stories were not very good, they would still provide significant historical interest. But they are good, which makes them all the more amazing. In “Nocturne,” for example, the narrator hovers above the action, wryly marking the minute steps by which sex blossoms. When the burglar’s hand first brushes Freddy’s, the burglar experiences a “feeling, shall we say, that does not enter his consciousness any further but nonetheless moves him to utter the words, ‘Jeez, a tiny hand … like a girl’s.’” The burglar later grabs Freddy to keep him from escaping: “In Freddy, however, powerful images awaken of Carmen, of Circe, of Santuzza.” Not only is the tale très gay, but so is the telling.

In the other four stories, each opening sentence locates the action in an actual specific place, grounding the story in a realism that gives us a glimpse into gay life at the time. Most interesting in this respect is “A Nemesis,” which begins: “Tiergarten, the central park in Berlin, near the Brandenburg Gate.” It’s night, the garden is cruisy, and Trudy, dressed in a sailor suit, is swaying his hips: “It is the flâneur’s well-practiced stride that shows (just as a merchant displays his wares in an easily surveyable and seductive manner) he’s available, promises discretion, and guarantees satisfaction.” Trudy picks up Erich, they begin an affair, and Trudy disappears. Erich’s search for Trudy takes him to two gay ballrooms, one lower-class with soldiers “and (of course!) sailors, both real and pretend ones,” the other elegant, where “choice attire, pleated trousers, and cologne prevail.” Granand’s detailed description of the participants and their codes of behavior is itself a fascinating piece of social history.

“American Style” starts on an express train to Milan, whose lurching propels a gay German man into a large straight American businessman, “who is as beautiful and strong as Siegfried.” In Milan, Franz opens up the practical American’s æsthetic side by taking him to see The Last Supper and The Elixir of Love, and one thing leads to another, as we have seen. “Cadets,” a more tender story, takes place in a boys’ military academy and captures adolescent confusion about friendship, love, and sex. It’s the most psychologically nuanced of the stories. Homosexuality is expected, if not completely accepted, by the other cadets, who casually refer to other boys’ “tricks,” even as the actual emotions involved are more complex.

The final story, “The Apparition,” is about a German man who, because “the police once got involved in his misfortune,” has moved to Paris, where he “has no more affairs and therefore no more sorrow”: “He’s achieved distance from life and become wise.” His detachment is challenged when a “young apache” (the translator notes the problematic word) tries to pick him up on the street. He refuses, but becomes obsessed and tries to find him again: “He had believed himself to stand above and apart from life and now he sees how easily all worldly wisdom can just go the devil if only a bit of lifeblood keeps coursing through your veins.” It’s the one story in which the invitation to sex meets resistance rather than surrender. And it’s the saddest story in the collection.

These stories, in short, are a celebration of gay sex: not comradely affection, not romantic friendship, but actual gay sex. It’s good to have access to them as a reminder of what was possible a hundred years ago.

Michael Schwartz is an associate editor for this magazine.