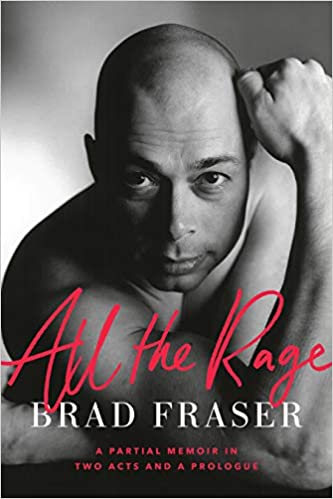

ALL THE RAGE

ALL THE RAGE

A Partial Memoir in Two Acts and a Prologue

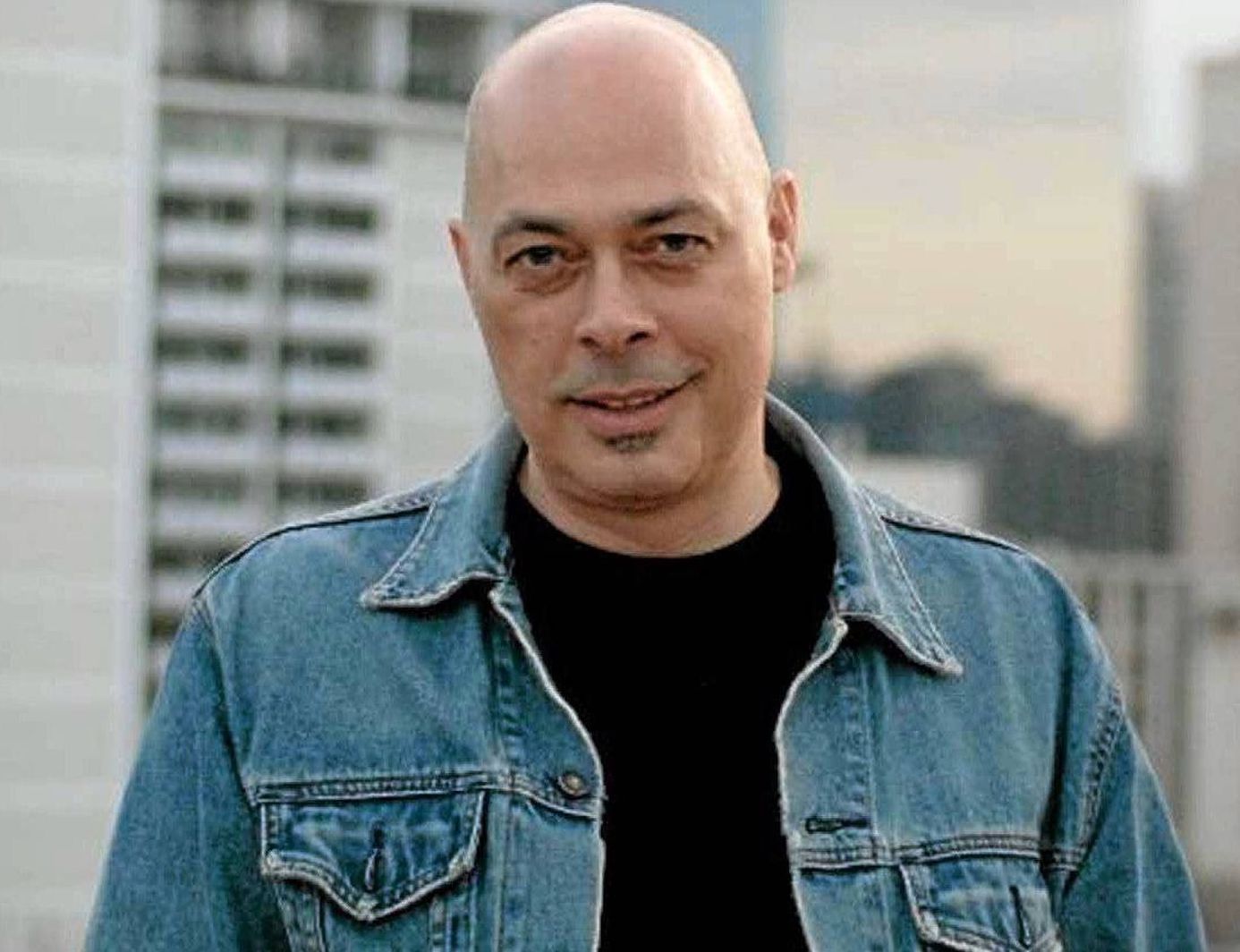

by Brad Fraser

Doubleday Canada. 342 pages, $26.95

A decade before Orton, John Osborne, one of England’s “angry young men” of the 1950s, changed British theater forever when his play Look Back in Anger opened at the Royal Court Theatre in London. Canada had to wait a generation for Brad Fraser to do the same for Canadian theater. At the Canadian premiere of Unidentified Human Remains, several people walked out at the midway point in Act One when a woman kisses her lesbian friend. “That delighted me,” reports Fraser. “I’ve always felt that [the kind of]theatre the right people walk out of is theatre that matters.” Early in the AIDS epidemic, an interviewer asked Fraser: “Do you have to be so angry all the time?” To which he replied: “Yes. I do. It’s the only thing that keeps me going while everyone around me is dying.”

All the Rage tells the story of how the young Bradley Fraser successfully channeled the emotions arising from an upbringing in an impoverished family, in which he endured emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, to become the award-winning Brad Fraser: “I knew that my upbringing had instilled a tremendous anger within me,” he writes at the end of the prologue, “and that if I didn’t find a way to channel that anger constructively it would end up directed at those around me or myself. I also knew it would trap me in the world I came from. Creative activities had always been the best way for me to channel my negative emotions and I knew my salvation would be with them.” It is that story that makes All the Rage read at times like an autobiographical novel.

All the Rage tells the story of how the young Bradley Fraser successfully channeled the emotions arising from an upbringing in an impoverished family, in which he endured emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, to become the award-winning Brad Fraser: “I knew that my upbringing had instilled a tremendous anger within me,” he writes at the end of the prologue, “and that if I didn’t find a way to channel that anger constructively it would end up directed at those around me or myself. I also knew it would trap me in the world I came from. Creative activities had always been the best way for me to channel my negative emotions and I knew my salvation would be with them.” It is that story that makes All the Rage read at times like an autobiographical novel.

The success of Fraser’s plays derives to some extent from his lifelong immersion in popular culture. “In my childhood dreams,” he confides, “I’d always imagined myself to be the illegitimate love child of Wonder Woman and the Empire State Building.” The plot of Unidentified Human Remains was inspired by the popularity of movies about serial killers in the 1980s, and the original subtitle of The Ugly Man (1992) was “A Gothic Horror Melodrama.” The former opens with a choric recounting of a Gothic urban legend: “The case of the headless boyfriend.” Poor Super Man was inspired by the “Death of Superman” issue of DC comics. In her foreword to The Ugly Man, Edmonton journalist Paula Simons points out that “audiences around the world respond to his plays because pop cult is the new lingua franca.”

All the Rage is a memoir for a wide range of readers. Every young person who aspires to be an artist should read it. Anyone who wants to better understand how potentially self-destructive anger can be transformed into art should too. It ought to be required reading for critics and scholars who want to understand the arc of Fraser’s career up to 1999.

An even better entrée to Brad Fraser would be to see one of his plays in live performance. Fraser is that rarity in contemporary theater whose political activism takes place in a darkened theater where the creative imagination rules, just as the subconscious does in dreams. His plays disturb our complacency and discomfit our assumptions. His introduction to Martin Yesterday is called “Saying Things People Don’t Want to Hear.” His most recent play, Kill Me Now, compels you to ask the uncomfortable question: Under what circumstances would I want to be killed rather than continue living? “Any good play has elements that make you uncomfortable,” he said in an interview about Kill Me Now. “Isn’t that the whole point of going to the theatre?”

Nils Clausson, a retired English professor living in Regina, Canada, has directed plays for Regina Little Theatre and served on its board of directors.