DEEP SONG

DEEP SONG

The Life and Work of Federico García Lorca

by Stephen Roberts

Reaktion Books. 240 pages, $35.

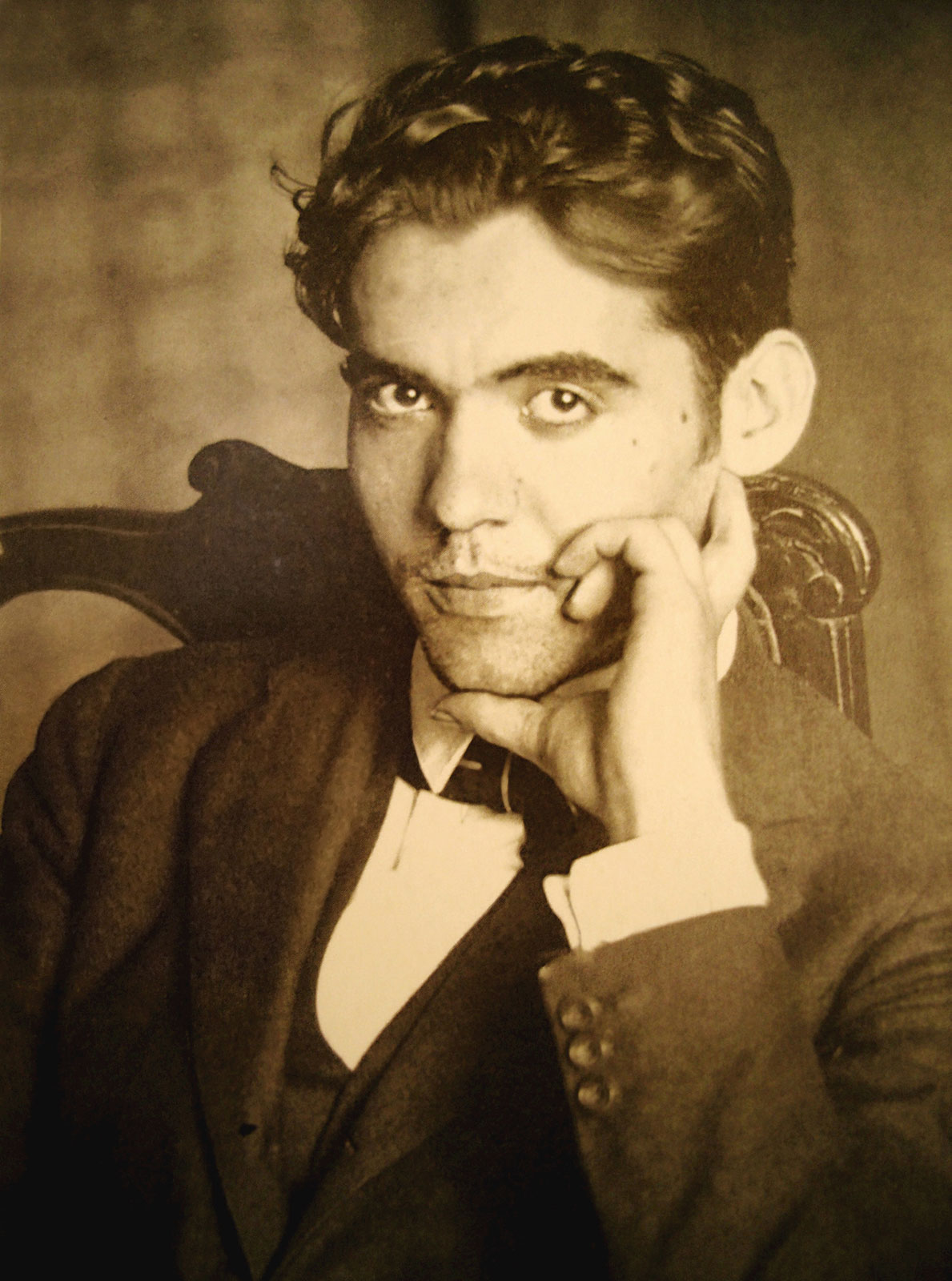

GORE VIDAL famously said that the three saddest words in English are Joyce Carol Oates. For gay readers, three of the most iconic words are Federico García Lorca. Known to readers in English mainly by his maternal surname, Lorca occupies a tense junction in the history of Spain, writing, and gay culture. Dead for over eighty years, he’s like a returning comet who fades for a time before reappearing in yet another book, monument, musical fantasia, or exhumation request. His gifts as a poet and dramatist, and the symbolic effect of his political murder at age 38, gave rise to a steady and remarkably varied artistic industry.

There’s a wealth of published material about Lorca, with Ian Gibson’s 1989 biography the anchor point to date. Gibson wrote several other books about Lorca, including one entirely about his assassination, an event that continues to fascinate the international public, despite the family’s wish for a memorial park instead of yet another search for his corpse. Unique offerings on the Lorquiana tray include a selection of his letters, a long memoir by his brother Francisco, and, perhaps of greatest interest to G&LR readers, Paul Binding’s 1985 Lorca: The Gay Imagination, which focuses specifically on Lorca and homosexuality. In addition to generating interest in his life, his work inspired many poets and gave rise to a speculative fire-dance of a novel about hypothetical immortal Lorcas, Carlos Rojas’ The Ingenious Gentleman and Poet Federico García Lorca Ascends to Hell. I’ll stop there; the material is vast and kaleidoscopic.

Now comes Deep Song: The Life and Work of Federico García Lorca, by Stephen Roberts, professor of Spanish culture at the University of Nottingham. It takes a certain confidence and clarity of intent to present a new biographical offering about such a well-known and vivid figure, with the faces of worthy predecessors gazing down like Lorca’s floating face in Salvador Dalí’s paintings. For the reader whose interest in Lorca is basic, Gibson’s biography will do. For those whose interest includes the details of how Lorca’s writing came to be and how it is linked to daily life and culture where he lived, Roberts offers a rewarding tour that, however detailed, never gets tedious.

Deep Song, a title borrowed from Lorca’s own work, starts with Lorca’s “García” roots in the countryside of southern Spain, a blended zone with many Arabic influences. It is also a place of interconnected family and business relationships. Some of these were helpful to the young writer and some ultimately fatal, Roberts argues with evidence gathered from multiple sources and laid together like the mosaics of Andalusia.

In all that he was and did, Lorca was a man of place. His poems overflow with the colors and smells of the land, his plays with the social and religious intensity of the old traditional homes and families in which he grew up, particularly with the thoughts and habits of the women of this society. His sense of disconnection when he lived in New York was palpable, less so during visits to Cuba and Argentina. But these places were still not quite his own, as was the countryside around Granada.

Roberts makes clear that Lorca was uniquely positioned in time and space to be the great flame of literature that he became, as he gathered artifacts of rural and religious culture, in some cases filtering his writing through a remarkable array of creative friends and acquaintances. His intellectual critics and collaborators included composer Manuel de Falla, Dalí, philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, filmmaker Luis Buñuel, and poet Jorge Guillén. The latter remarked that Lorca’s lively and colorful personality was like an entire atmosphere and weather system.

We learn here that Lorca was liberal toward people and new ideas but fundamentally conservative in how he viewed his own roots. Strongly connected to rural agrarian culture and marinated in the deeply traditional Spanish Catholic Church, laden with saints and symbols, he lived and worked in the difficult junction between his nonconforming sexual life and his traditionalist culture. He was supported in college by his wealthy family but became something of a ne’er-do-well, eventually called to task to finish his formal education. This resulted in his getting a singularly inappropriate degree in law.

The young Lorca, bullied as “Federica” when a schoolboy owing to his effeminate ways, was by all accounts something of a slut once he achieved a level of comfort about his desires. He became known for matter-of-factly asking for sex and indulging in it whenever he could. Nor could he be called discreet: he was part of a traveling theater group in the 1930s that some critics called “Sodom on wheels.”

Murdered in 1936 by right-wing Nationalists near Granada, the hometown that had inspired so much of his best work, Lorca the martyr gained even greater fame, which proved an irritant not only to the Franco regime but to Spanish authorities ever since. In a song about Lorca by Shane MacGowan of The Pogues, one line goes: “Lorca’s corpse, as he had prophesied, just walked away.” The circumstances of his murder are mysterious; some still seek his bones beneath the dusty stones of Spain.

Alan Contreras, a writer based in Eugene, OR, is the author of The Captured Flame: Notes on Books, Music, and the Creative Force.