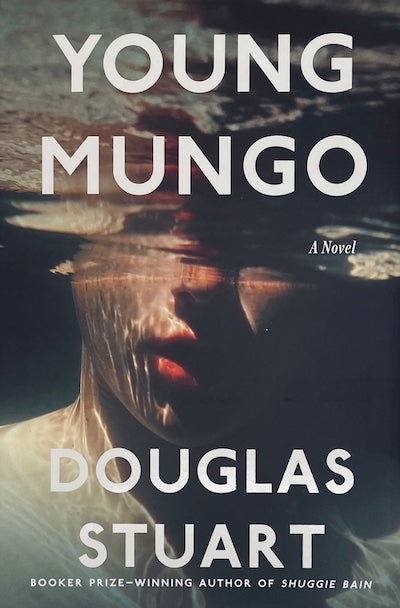

TWO NOVELS published in the span of two years have made 46-year-old Scottish-American Douglas Stuart a writer to be reckoned with. He labored quietly for ten years on his first, Shuggie Bain, a heart-rending portrait of a mother and son published in 2020, and then began his second, the recently published Young Mungo. Shuggie Bain won the Booker Prize, making Stuart only the second Scot to win the prestigious international award (James Kelman being the first, in 1994). Stuart’s work has garnered glittering reviews on both sides of the Atlantic; Shuggie Bain has been called “the most globally significant Scottish cultural phenomenon since the mid-1990s successes of Trainspotting and Braveheart.”

Stuart did not start out as a writer but as a fashion designer. Reared in housing projects on the East End of Glasgow by his alcoholic mother, who died when he was sixteen, he put himself through trade school and college, then moved to New York City, where he lives with his husband today. In short, he is a self-identified queer, working class, Scottish literary star. Formed in Glasgow, his love for the sectarian-riven city is heartfelt, his prose is lightly peppered with Scots vocabulary, and his characters speak in varying degrees of phonetic Glaswegian dialect. His Glasgow of the 1980s and ’90s is haunted by addiction, violence, and an “uppity ginger bitch,” better known as Margaret Thatcher, whose demoralizing economic policies are felt to this day. Young Mungo concerns two gentle, adolescent boys who find each other among the ruins. Mungo, age fifteen, a Protestant, lives with his teenage sister Jodie; occasionally with his mother, Mo-Maw, or her boozy alter ego Tattie-bogle (“scarecrow” in Scots), who sends Mungo on a sinister fishing weekend with two besotted strangers whom she has instructed to “make a man” out of him; and sometimes with his gang-leader brother Hamish, a cipher of dejected humanity, who believes his fraternal duty is to teach Mungo to “man up.” James, almost sixteen, a Catholic, lives alone because his widowed father works on a North Sea oil platform for weeks at a time. James breeds racing pigeons in a makeshift dovecot, which is where the boys first meet. As in the novels of Dorothy Allison, Jim Grimsley, and Justin Torres, economic destitution is not simply background for these child protagonists; it is integral to who they are. Stuart renders a dangerous world, unmoored from contemporary notions of gay or lesbian identity. LGBT children typically know they’re different before they understand what sexual attraction is. Mungo and James have discovered those feelings, but the primary model for what awaits them in adulthood is an older, effeminate neighbor known contemptuously as Poor-Wee-Chickie, who survives by deflection and grit, daily navigating people who despise him. The boys have an inkling that life exists elsewhere, but it is a vague notion. One of Stuart’s accomplishments is to conjure the depth of their longings. Mungo and James’ longings for friendship and the erotic are indistinguishable. The electricity when their pinkie fingers deliberately touch overwhelms them. Gradually each boy begins to accept emotional intimacy from the other, though the sex doesn’t go beyond holding hands, kissing, and masturbating. This is a love story in a crucible, kindled by longing and sustained by innocence. The boys can only guess at the extent to which other characters recognize their’ nature, knowing that beatings, ostracism, or even death await them if they’re discovered. But they take risks anyway. The gut-wrenching violence in Young Mungo is delivered in calm and elegant prose. Stuarts’ descriptive powers can be lyrical, but he doesn’t wallow in the misery; he merely chronicles it. And just when you want to fling the book across the room, Stuart surprises you: he digs deeper; something poignant surfaces; he exalts courage or benevolence. What makes his often bleak and savage narrative bearable, in addition to the beauty of his writing, is that the characters, even the most detestable, are complex enough that their humanity cannot be dismissed. When Mungo, Jodie, and Poor-Wee-Chickie attempt to intervene in a potentially lethal scene of domestic abuse, Stuart weaves in a political and emotional context that penetrates the behavior of all the participants. We’re given a chance to empathize with everyone involved. Stuart creates tension in both of his novels through opposition: the performance of male cruelty against acts of tenderness. As the story barrels toward its close, fear rules, the closet door is locked on both sides, but nothing is as tidy or certain as in Romeo and Juliet, to which Young Mungo has been awkwardly compared. There are glimmers of longing that should not be mistaken for garden-variety hope.

Thomas Keith edits the Tennessee Williams titles for New Directions Publishing and co-edited Williams’ letters for W. W. Norton.