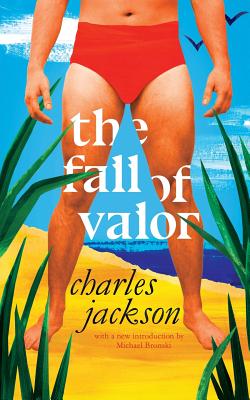

The Fall of Valor

The Fall of Valor

by Charles Jackson

Valancourt Books. 223 pages, $19.90

IN 1944, Charles Jackson (1903-1968) published The Lost Weekend, about a writer battling alcoholism. The novel and especially the film version, which won Best Picture for 1945, were so successful that the title entered the language: we’ve all had our lost weekends. Jackson wrote the novel largely from his own lifelong struggle with alcohol and drugs. Two years later, he published a novel called The Fall of Valor (1946), which describes a married man’s love for a Marine.

Because of the success of the earlier novel, The Fall of Valor received attention from the major reviewers, such as Edmund Wilson for The New Yorker and Diana Trilling for The Nation. The New York Times reviewed it twice. One reviewer, mentioning Proust and Gide, found Jackson wanting: “Charles Jackson, for his second novel, has hit upon a subject that has been treated by experts. Such an expert, in the precise sense of the word, Mr. Jackson quite obviously is not—happily for himself, and unhappily for The Fall of Valor.” In fact, Jackson, though married with children, was expert in homosexuality. As Michael Bronski points out in his introduction to this edition, Jackson “had a series of male companions including, for the last year of his life, the faithful Stanley Kednick, a Czech émigré twenty years his junior,” who was living with him in the Chelsea Hotel when Jackson committed suicide by a barbiturate overdose.

Set in 1943, the novel centers on John Grandin, a 44-year-old college professor who is married with two children. It begins with John in New York City and his wife Ethel in Maine, both taking trains to their vacation destination, the ferry for Nantucket. In alternating chapters, the train trips let the two ponder their lives. John feels an “inexplicable anxiety … a sense that something was about to happen to him, something untoward, perverse, impossible to fit into his comfortably ordered life.” Ethel is more focused on the marriage and how John’s withdrawal into his work has left her “so unsatisfied in love that sometimes she thought she couldn’t bear it.” While Ethel’s love for John includes sexual desire, John “looked forward to the time when their marriage would become a habit even more.” On the train, John meets Cliff, a Marine who is “truly a giant, six-feet-two or -three, and heavily built: enormous shoulders, large head, blond curling hair, blue eyes—the athlete, the American idol, uninteresting.” Uninteresting, at least at first. Cliff, on medical leave after combat in the South Pacific, is on his way to his honeymoon with his bride Billie.

On their first night on Nantucket, Ethel explicitly confronts John with his diminished sexual interest. The confrontation drives a wedge between them, and into the vacuum come Cliff and Billie—especially Cliff, with his intense and insistent friendliness toward “Johnnie,” as he calls him, which gives John an unaccountable pleasure. John’s interest in Cliff grows, although his self-awareness does not. John and Cliff are changing out of bathing suits: “Out of a kind of furtive curiosity, Grandin could not keep from stealing a glance or two at the exposed and splendid physique. It was heroic: Hercules, Hector, a younger Odysseus, seen as they were never seen in the storybooks, and made modern by the startling whiteness of the hips above and below the tan.” He later rebuffs Cliff, angrily and unexpectedly, as Cliff tries to put suntan oil on his back. Remembering the moment later, John finally sees his own desire: “It was an act so personal and intimate that he could not have stood it. And suddenly, to his horror, he felt a slow rude pressure growing in his loins.” The rest of the novel tracks the fallout from this realization: Ethel’s reaction, John’s continuously shifting understanding of his own desire, and his attempts to interpret Cliff’s aggressive friendliness and ambiguous words and actions.

When faced with an older gay novel, our first question is whether it’s going to hold anything other than antiquarian interest. The Fall of Valor isn’t even a very gay novel: the protagonist doesn’t realize the nature of his desire until page 166, less than sixty pages from the end. It’s also not a “problem novel” about homosexuality as an abstract issue, and John is in no way an Everyman with a universal coming-out story. Jackson doesn’t try to explain Grandin’s homosexuality, either what caused it or how he avoided knowing about it for so long, or why he is specifically attracted to Cliff, or whether this attraction makes him bi- or homosexual. Instead, this is a novel, and a well-made novel, about a particular man in a particular situation. Its value resides in this particularity.

Jackson uses third-person, semi-omniscient narration to keep us mostly in John’s consciousness. Through his thoughts and reactions, we see an intelligent, self-analytical mind at work, but one whose self-knowledge always lags: that is the dramatic motor of the novel. Other chapters show Ethel’s thoughts about John. While they both ponder their marriage, however, Jackson plants hints, not understood by them, of John’s homoerotic stirrings. On her train ride, Ethel remembers finding a newspaper photograph of a sleeping Marine under John’s desk blotter: “The photograph had a compelling beauty; realistic in the extreme, yet poetic, it evoked the Drum-Taps poems of Whitman of which her husband was so fond.”

On his parallel train ride, John sees a magazine picture of four dead Marines on a beach, leading him to ponder how “the solitariness of death was brought home with a peculiar, a melancholy beauty.” He also invokes Whitman, who “had celebrated the beauty of death in many a challenging manly chant.” After meeting Cliff, John’s analysis begins to stumble. At one point, he is watching Cliff and picturing him dead in combat. Cliff suddenly smiles at him: “Undone, John Grandin felt himself slipping into a peculiar morass of emotion, unprecedented in his experience: sadness, desire for he knew not what, admiration, and a foolish wish that it might be he who was to die instead.” In this way, Jackson shows 166 pages of a life lived in heterosexual complacency, although occasionally and increasingly disturbed by homoerotic flashes—a complacency shaken by Ethel’s sexual needs and finally destroyed by Cliff’s destabilizing, ambiguous masculinity.

Crucially, Jackson never takes us inside Cliff’s mind. We see only what John sees, Cliff’s ambiguous words and actions, and we are left, as is John, with the task of interpreting them. It’s not easy. Cliff seems bored with his bride, eager to return to the war and his buddies: “I sure miss it, and the fellows.” Another character comments: “The way he goes on about Johnnie-and-I-this and Johnnie-and-I-that. … My god, he talks as though you two wives didn’t exist.” His feelings toward John go beyond respect or even idol-worship. But what are they, exactly?

Interestingly, the early reviewers assumed, as Edmund Wilson asserted, that “the Marine is homosexual, too,” though “he is childishly unconscious of his tendencies.” Diana Trilling even commended Jackson’s “perception of the sexual ambivalence of the ultra-masculine, football-player type of men.” But Jackson is after something more interesting than a closet case. He makes Cliff impossible to read, for us as well as for John, thereby making John face the key question in gay life, especially in a more closeted era: does he want what I want? Correctly interpreting a seemingly straight man’s words and actions can lead to love. Being wrong can lead to a vicious beating. Jackson keeps Cliff’s ambiguity completely intact, until the closing pages of the novel.

Finally, John’s attraction to Cliff is part of—and even arises from—the general homoeroticism of the wartime atmosphere. On the train ride, John sees a group of older civilian men around a paratrooper: John is “touched and disturbed to notice how intense … was the feeling of admiration, even affection, for this youth whom they did not know. It was the uniform, of course, plus the danger; plus the fact that they were not young.” The constant presence of soldiers and Marines creates an atmosphere of death-soaked masculinity that provides a cover for John’s homoerotic desires. John can invoke A. E. Housman and Walt Whitman and their love for soldiers without having to admit that the poeticized love is in fact sexual desire.

As John comes to know Cliff, his gaze becomes more focused on the Marine. On the beach, he notices a crowd watching Cliff: “He sensed that the whole beach had begun to fall a little in love with Cliff.” Later, he attends a military ball at Cliff’s invitation: “The clubhouse had become charged with an atmosphere of youth, an oppressive feeling of young masculinity so real as to become almost tangible.” As Cliff enters in his dress whites, “Here again, but more than ever now, was the hero out of Homer—Hector or Achilles—or Lancelot (far more than Galahad), Siegfried, Jason of the Argonauts, who had been his boyhood companions.” This is the night when John finally understands his own desire.

The Fall of Valor, then, is very much a novel of its time. Because Jackson has captured that time so exactly, it becomes a novel for our time as well.

Michael Schwartz is an associate editor of this magazine.