The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture

The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture

by Heike Bauer

Temple University Press

236 pages, $34.95

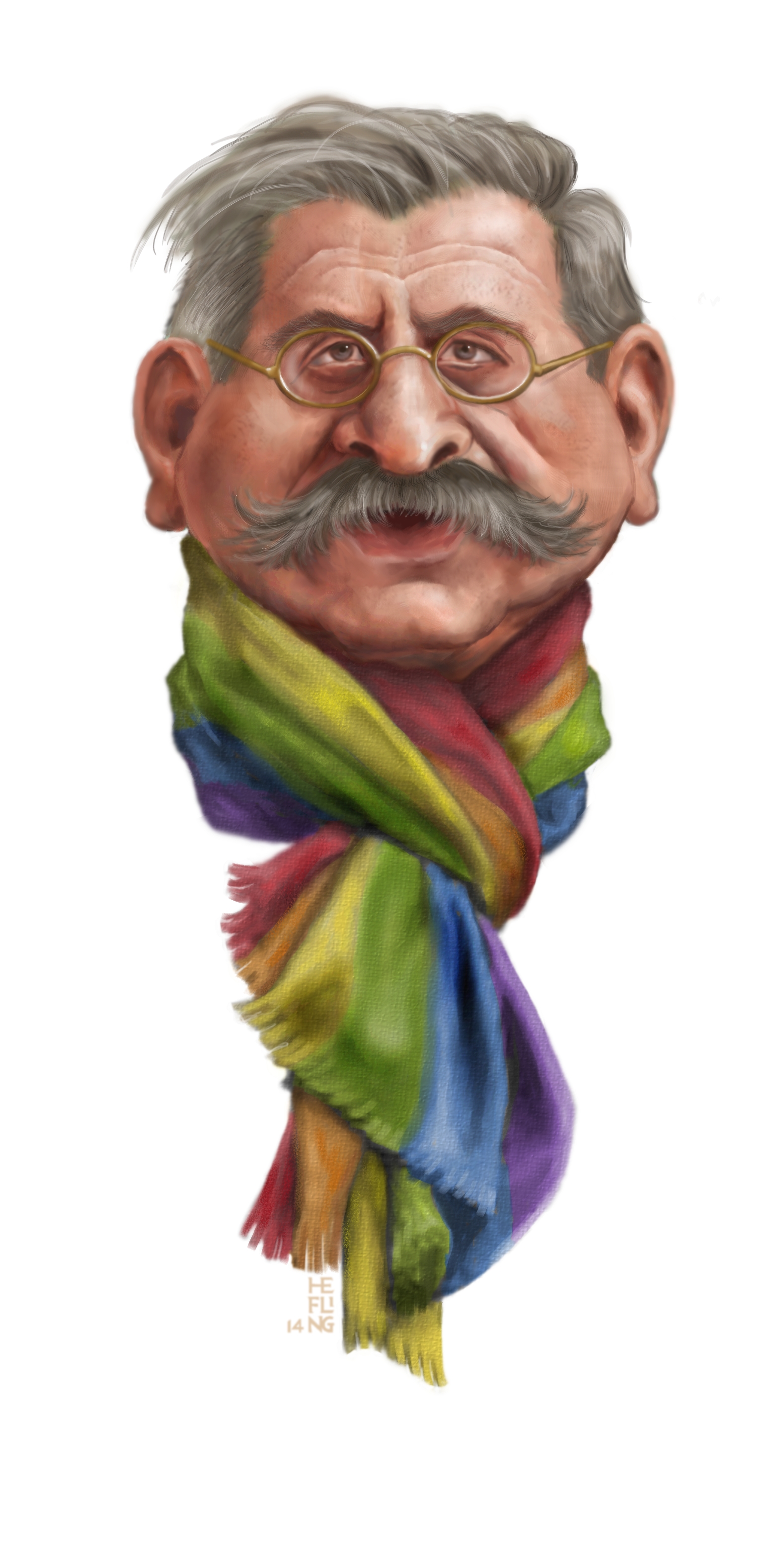

MAGNUS HIRSCHFELD (1868–1935) was hailed in the press as the “Einstein of Sex” during an American lecture tour in 1930. He was a leader among the pioneering sexologists of the late 19th century, and the first openly homosexual one. Although his focus was on matters of sexuality, he was an outspoken radical on many other controversial topics, such as feminism, racism, anti-Semitism, socialism, and even nudism.

Born into a Pomeranian (German) Jewish family, his father was a physician and a regular writer on humanitarian issues. Hirschfeld was equally divided between a career in medicine or literature. After studies in philology and medicine, he took off on an extended tour of the United States, documenting his experiences in German newspapers. In 1896, he established a medical practice in Berlin and began publishing in defense of same-sex love. He helped organize the Scientific Humanitarian Committee in 1897 to deploy scientific arguments in support of homosexual civil rights and the decriminalization of sodomy. The Committee began publishing a journal on “sexual intermediates” (sexuelle Zwischenstufen) in 1899 under Hirschfeld’s editorship. His own research and publications covered a spectrum of sexualities and genders: homosexuality, “third sex,” transvestism, bisexuality, and transgenderism. He even documented the homosexual bars and cabarets of 1920s Berlin.

Just three months after the appointment of Hitler as chancellor of Germany in 1933, the Nazis targeted the Institute for Sexual Science that Hirschfeld had dedicated his life to building. Hitler Youth ransacked the building on May 6, followed by storm troopers, who confiscated books and files. This was followed a few days later by notorious public book burnings and Nazis parading a bust of Hirschfeld on a stake before throwing it on a bonfire of books. Hirschfeld—as a Jew, a homosexual, and a leftist—was a triple target for Nazi persecution. At the time, Hirschfeld was already living in exile in France in a ménage-à-trois with his long-term partner, Karl Giese, and a young Chinese medical student, Li Shiu Tong (aka Tao Li, “beloved disciple”).

Just three months after the appointment of Hitler as chancellor of Germany in 1933, the Nazis targeted the Institute for Sexual Science that Hirschfeld had dedicated his life to building. Hitler Youth ransacked the building on May 6, followed by storm troopers, who confiscated books and files. This was followed a few days later by notorious public book burnings and Nazis parading a bust of Hirschfeld on a stake before throwing it on a bonfire of books. Hirschfeld—as a Jew, a homosexual, and a leftist—was a triple target for Nazi persecution. At the time, Hirschfeld was already living in exile in France in a ménage-à-trois with his long-term partner, Karl Giese, and a young Chinese medical student, Li Shiu Tong (aka Tao Li, “beloved disciple”).

Hirschfeld died two years later in Nice of a heart attack and seems to have fallen into obscurity. This may have been due to the fact that his will left his estate to his two lovers with the stipulation that the inheritance was “not for personal use, but solely for the purposes of sexology.” Giese ended up living in poverty and committed suicide in 1938. Li moved around for school (including a stint at Harvard), shifting from medicine to economics, never completing a degree, and then vanished.

Hirschfeld’s legacy almost went up in smoke as well. It seemed that most of the Institute’s library and archives had been destroyed. A few of his works were available in (poor) English translations. Until the 1990s, historical work on Hirschfeld’s life was largely limited to the scholarship of Manfred Herzer, Charlotte Wolff, and James Steakley. However, a group of dedicated scholars in West Berlin had founded the Magnus Hirschfeld Society in 1982, and began to track down the Institute’s library and archives. Thanks to these newly available materials, there has been a renaissance of Hirschfeld studies in the 21st century. Hirschfeld even became a recurring character in Season 2 of the Emmy-winning Amazon series Transparent. However, don’t expect great historical accuracy there (spoiler alert): Hirschfeld was not in Berlin to witness the looting of the Institute. Instead, he learned of it from a newsreel in a Paris movie theater with his lover, Li. Hirschfeld spent his last years trying to salvage what he could of his collections, which were left to his lovers upon his death.

The mysteries surrounding these materials continues to unfold. In 2002, Magnus Hirschfeld Society director Ralf Dose was able to track down Li and some of the materials in his possession. Quite serendipitously, a man had found some of Hirschfeld’s and Li’s papers and photographs in a dumpster in Vancouver in 1993. He later posted a note about this on an Internet forum, which only came to Dose’s attention almost a decade later. It turns out Li had moved to Vancouver in the 1970s, where he died in 1993. Like a master detective, Dose tracked down Li from his tombstone to his surviving younger brother, who had cleared out Li’s apartment upon his death. Nevertheless, the brother had preserved in his basement what remained of the Hirschfeld collection.

§

The trials and tribulations of Hirschfeld and his archives are worthy of their own TV show. No one is more familiar with Hirschfeld’s life and work than historian Heike Bauer, a Senior Lecturer at Birkbeck College, University of London. She has written extensively on British and German sexology of the fin-de-siècle. Bauer relates the latest tragic episode in this saga. In trying to access the Hirschfeld-Li archives that were supposed to be at the University of Minnesota (Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies), she discovered they had gone missing. Reportedly, the boxes of archives shipped from Germany had arrived empty!

It does seem that Hirschfeld’s archives have suffered tremendous violence, which is emblematic of their subject matter and namesake. Hirschfeld suffered as a Jew and a homosexual; and research by him and others on marginalized sexualities has suffered from poor funding, condemnation, and historical neglect. His life and works have enjoyed well-deserved renewed attention, and the bones of what remain of his archives seem to have been picked clean. Therefore, in The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture, Bauer takes a subtle and sensitive approach to exploring what might be missing or silenced from Hirschfeld’s research and writings, particularly in light of contemporary queer politics and theorizing. Bauer’s critique is a corrective (maybe an over-corrective) to some of the hagiographic early studies of Hirschfeld as a “pioneer of gay rights,” the inventor of transvestism and transsexualism, and the first “out” gay physician.

Bauer finds that Hirschfeld was insufficiently critical of German colonial engagements and the racist scientific theories that legitimized the control and exploitation of so-called inferior races. The focus behind Hirschfeld’s and the Institute’s work was “sexual intermediaries”: a variety of genders and sexualities that today we might identify (partly thanks to Hirschfeld) as gay, bisexual, transgender, gender queer, etc. He relied on a scientific rationale that this range of sexualities was biologically (even genetically) based. In Hirschfeld’s arguments in the press and in court testimony, this genetic basis is part of human diversity. Hirschfeld was also an advocate of progressive eugenics, seen as informing public health, family planning, and women’s liberation. However, these types of genetic arguments also would be used by the Nazi’s not for liberating purposes but for involuntary “race hygiene” and genetic cleansing.

Bauer also finds that Hirschfeld, in his attempts to defend same-sex attraction, did not adequately condemn pedophilia and child sexual exploitation. This was especially relevant at the time, since a large segment of early homosexual defenders in Berlin (including Institute supporters) vocally idealized classical models of pederastia (erotic mentorship of adolescent males by adult men).

The institute was a haven for gender bending people (as Transparent dramatizes), with not only assessment and medical care but even employment and rooms. Bauer finds it problematic that these third-gender people were also used as research subjects and photographed for the archives. Certainly by today’s ethical standards this would not be permitted. But these were very different times: Freud shared meals with patients, and had them join him while on vacation.

As noted, Hirschfeld was on an extended global speaking tour (started in 1930), when he realized it would no longer be safe to return to Germany. His observations from that experience were published in 1933 as Die Weltreise eines Sexualforschers (“The World Journey of a Sexologist”). His comments have been praised as exceptionally progressive: favoring leftist politics, feminism, anti-colonialism. Bauer reads between the lines and more deeply to find that Hirschfeld tended to favor Western and male informants, and sometimes skewed his remarks in heterosexist ways to accommodate conservative audiences. While he was a secularist and critical of racial definitions of Jewishness, he supported Zionism and the proto-kibbutzim, since they engaged in radical innovations in sexuality, communal child rearing, and positive attitudes about the body. Bauer faults him for neglecting the plight of Palestinian Arabs by supporting Zionism instead.

Bauer’s broad critique is that Hirschfeld’s focus on homosexual rights led him to neglect other human rights issues, including the violence against a range of queer people for reasons other than sexual orientation: race, religion, gender. It’s hard to argue with this present-biased analysis: even the most progressive white, male professionals of the 19th century have a slight crust of un-PC prejudice to them from today’s perspective. Hirschfeld is no exception. But for his time, he was a political radical across the board. His motto, engraved on his tombstone, was “Per scientiam ad justitiam” (“Justice through science”). It epitomized the Enlightenment philosophy of liberal physician-scientists of the 19th century, confident that the objectivity of scientific knowledge on a range of social topics, from sexuality to criminality, could sweep away ancient religious moralism and outdated legal bias.

That optimism already seemed naïve at the end of Hirschfeld’s life, as the Nazis were poised to embark on campaigns of sterilization and extermination in the name of science. That said, even if the hypotheses, practices, and uses of science are just as infused with societal values and politics as any other cultural institution, we depend on the elusive ideal of objectivity. When scientific data and conclusions are insidiously and cynically undermined for political purposes, as is currently being done by the U.S. administration, critical vigilance of the political workings of science—whether in the early 20th century or now—remains a vital task.

Vernon Rosario is a child psychiatrist and Associate Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UCLA. He is the author of Homosexuality and Science: A Guide to the Debates.