THE EINSTEIN OF SEX

THE EINSTEIN OF SEX

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, Visionary of Weimar Berlin

by Daniel Brook

W. W. Norton. 320 pages, $32.99

RACISM AND THE MAKING OF GAY RIGHTS

RACISM AND THE MAKING OF GAY RIGHTS

A Sexologist, His Student, and the Empire of Queer Love

by Laurie Marhoefer

Univ. of Toronto. 334 pages, $36.95

THE INTERMEDIARIES

THE INTERMEDIARIES

A Weimar Story

by Brandy Schillace

W. W. Norton. 352 pages, $31.99

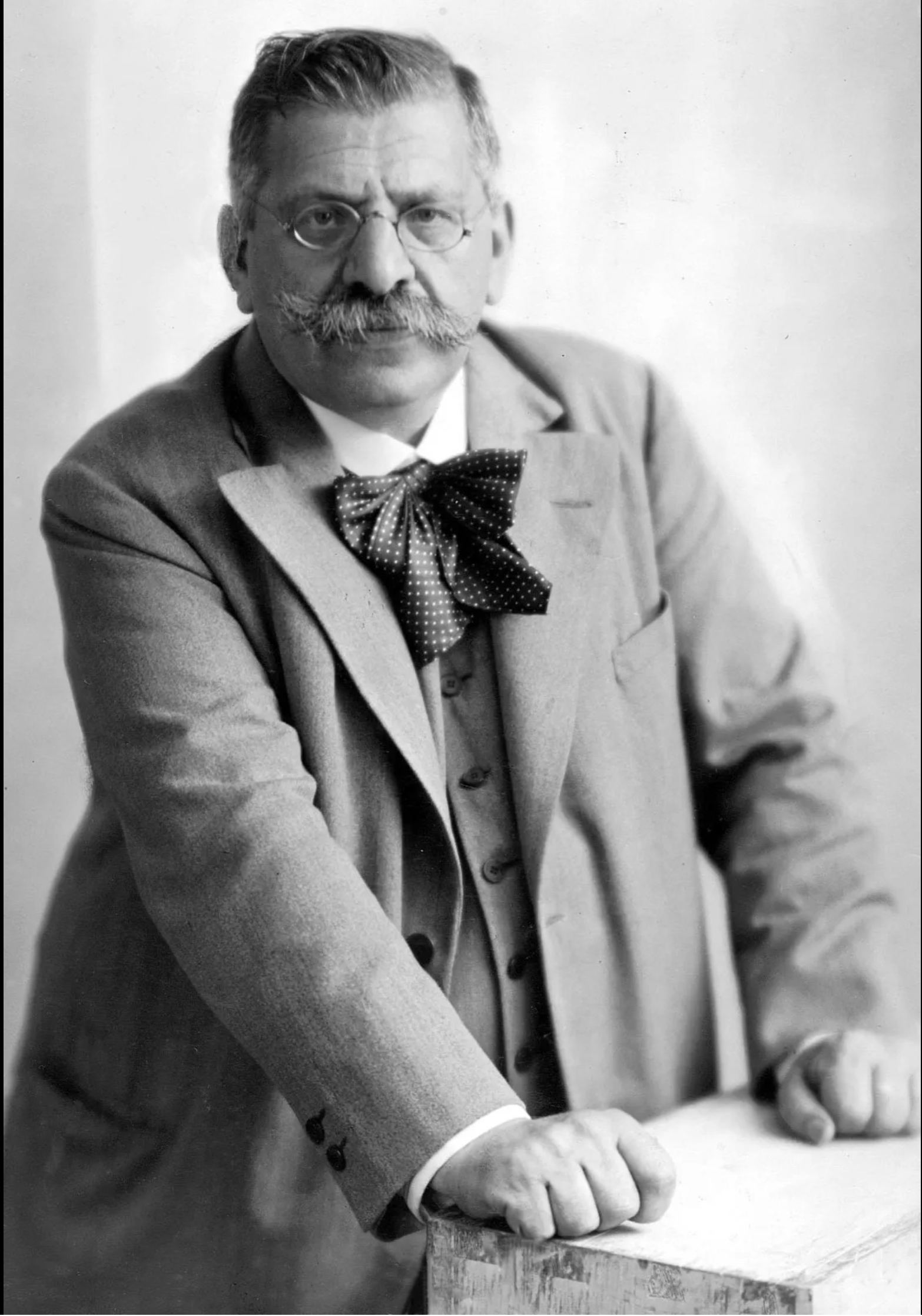

MAGNUS HIRSCHFELD (1868–1935) has benefited from a surge of interest in the past two decades and is frequently mentioned in these pages. While German historians have extensively studied his numerous publications, these have only become available in accurate English translations in this century thanks to the dedicated scholarship of Michael Lombardi-Nash. Hirschfeld is probably the only fin-de-siècle German sexologist scripted into an American TV show: In Transparent he appears in multiple flashbacks linking the title character (Jeffrey Tambor as Maura Pfefferman) to the Nazi persecution of Jews and sexual minorities. Hirschfeld was one of the most vocal proponents for progressive causes in the early 20th century—including women’s rights and the decriminalization of homosexuality. His activism and research led him to become one of the best-known sexologists of his time—so much so that the American press (with some degree of puffery) promoted him as “the Einstein of Sex” during a U.S. speaking tour in the 1930s. Three recent American books exploring Hirschfeld’s life and achievements present an array of assessments from underappreciated queer hero to utterly undeserving of queer sainthood.

The unified German Empire of 1871 adopted a conservative Prussian penal code, including a male anti-sodomy law (“Paragraph 175”), an anti-abortion law, and the criminalization of prostitution. These became the targets of multiple reform-minded, progressive women and men. Hirschfeld helped coalesce these interests in 1897 under the umbrella of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee) (SHC). The name was carefully chosen to downplay homosexuality and highlight the enlightened, scientific aspect of universal human rights. The SHC would eventually find a home in the Institute for Sexual Science (Institut für Sexualwissenschaft) established by Hirschfeld in the center of Berlin. The Institute housed a medical clinic, meeting rooms for progressive causes, residences for queer folks, and a sexology museum. He edited the Institute’s journal Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Homosexualität (“Yearbook of Sexual Intermediaries with Special Emphasis on Homosexuality”), published from 1899 to 1933. In 1921, in Berlin, he organized the First International Congress for Sexual Reform on the Basis of Sexual Science, which formed the basis for the World League for Sexual Reform. The League’s conferences drew progressive scientists and scholars from around the globe who advocated for science-based, enlightened sexual rights. The League’s platform included: the scientific understanding of intersexuality and homosexuality; the decriminalization of same-sex relations, prostitution, and birth control; equal rights for women and men; sex education; and eugenic birth selection (more on this later).

Despite this lifetime of leadership on homosexual rights, Hirschfeld was not publicly “out.” He was in a decades-long relationship with a young archivist, Karl Giese (1898–1938), who lived with him at the Institute. In 1931, Hirschfeld also became involved with a young Chinese medical student, Li Shiu Tong (1907–1993). He met Li during his Asian travels and groomed him to be his successor at the Institute. Li, Giese, and Hirschfeld seem to have become an amicable throuple until Hirschfeld died of a stroke in 1935. He probably did not want to risk discrediting his sexological and advocacy work by publicly identifying himself as homosexual. Yet his publication and activism history leaves little doubt about his sexuality. His first (pseudonymously) published defense of homosexuality, Sappho und Sokrates (1896), was prompted by tragedy: “[I] was moved to write [this book]by the suicide of a young officer, one of my patients, who shot himself on the night he married, and left me his confession.” Paragraph 175 led to shame, deception, blackmail, and suffering.

The work follows the lead of the pioneering legal defender of homosexuality, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825–1895), in presenting same-sex love as a congenital, biological variant of nature rather than an immoral sin, sexual perversion, or mental disorder. Ulrichs initially used the term “Uranian” for men born with a feminine nature. Invoking venerated figures from Classical Greece, Hirschfeld made the case for the antiquity and respectability of same-sex love. His biological model (which he would keep developing through his research) was that sexual nature is a combination of physical and neuropsychological factors between the “full female” (Vollweib) and “full male” (Vollmann). Since he viewed these poles as somewhat Platonic ideals, really all individuals are sexual intermediaries (sexuelle Zwischenstufen). He was generalizing a common late-19th century medical model that viewed “sexual inverts” as “psycho-sexual hermaphrodites.”

He launched into data collection to support his theories with a series of psychosexual questionnaires of polytechnic students and metalworkers. Although response rates were not great, he still found that more than one percent of respondents were primarily homosexual and three times as many were attracted to both sexes. His next book, Berlin’s Third Sex (Berlins drittes Geschlecht, 1904), took readers on a tour of the city’s already thriving and colorful gay nightlife. This would grow exponentially during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) (memorably depicted in Cabaret and Babylon Berlin). In 1910 he coined the word “transvestite” when he published Die Transvestiten: Eine Untersuchung über den Erotischen Verkleidungstrieb (translated only in 1991 as The Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress). As was typical of medical texts at the time, it uses case studies to describe a spectrum of “sexual minorities” (a concept he also coined): people who cross-dress as homosexuals as well as out of a deep cross-gendered drive. A decade later, he would go on to coin the word “transsexualismus” (though in the context of “intersexual constitution”). Until 1933, his Institute would be one of the first clinics to provide medical and surgical services to those wishing to achieve their inner gender through somatic interventions. It was thanks to this pioneering work that he appears in Transparent.

In all these publications, Hirschfeld argued for the naturalness of these “atypical” people, and their potential to be talented and respectable citizens—if only society did not condemn them. Persecution only led to depression and suicide, or forced marriages. As a firm believer in eugenics (meaning “improvement of the race through birth selection”), Hirschfeld feared that the offspring of these forced marriages were at risk of poor health. Arising in the late 19th century, eugenics began as a mainstream, scientific, progressive movement. Margaret Sanger, the birth control activist and founder of Planned Parenthood, was a supporter of women’s reproductive rights with the goal of selective breeding and racial improvement. As mentioned earlier, the SHC held eugenics as one of its main planks—with the support of many other early women’s rights activists.

§

Given the complexities and contradictions of Hirschfeld’s life, career, and activism, it’s not surprising that the three recent books on him present a range of interpretations. For readers completely unfamiliar with Hirschfeld, journalist Daniel Brook’s The Einstein of Sex is a good place to start. Brook admits he’d never heard of Hirschfeld before 2009 and lacks fluency in German. He approaches his subject with the wide-eyed enthusiasm of a new discovery and assumes no one else knows him. This is a fairly chronological biography and the most hagiographic of the trio. Brook is rightly impressed by Hirschfeld’s courage in advocating for homosexuals and as a martyr of Nazi anti-Semitism. He takes the “Einstein of Sex” moniker seriously, depicting Hirschfeld as developing an Einsteinian theory of sexual relativity with the spectrum model of sex. He provides a great deal of helpful political-historical context for this turbulent first half of the 20th century.

Already in 1920 Hirschfeld was heckled by hooligans—probably equally for his “decadent” views on sexuality and for being Jewish. In Munich he was so severely attacked by fascists that The New York Times published an (erroneous) obituary announcing the assault by an “anti-Jewish mob.” It was an early warning about the rising Nazi threat. The Institute was notoriously ransacked by Nazi students in May 1933 as an example of decadent Jewish activity. Storm troopers later seized valuables and held a well-publicized book burning of its library and archives—tossing in a bust of Hirschfeld. Fortunately, he wasn’t there to witness the destruction of his life’s work (as dramatically depicted in Transparent). Instead, he learned of it in self-imposed exile, watching a movie newsreel in Zurich.

Brook’s volume is very readable, with engaging novelistic speculation about dramatic moments in Hirschfeld’s life. He consistently presents Hirschfeld as a heroic defender of homosexual, trans, Jewish, and women’s rights.

For a less hagiographic and more academic take, readers can turn to Laurie Marhoefer’s Racism and the Making of Gay Rights. Marhoefer is a true specialist in the early 20th-century German history of sexuality. She brings scholarly familiarity with primary and secondary sources in English and German. Most interestingly, she delves into archival material on Li Shiu Tong, Hirschfeld’s “translator,” “Chinese pupil,” and probable lover for the last five years of his life in exile. Her writing is as accessible as her critique is unsparing. She holds Hirschfeld up to a presentist level of political scrutiny.

On all the issues for which Brook presents Hirschfeld as radical—race, feminism, colonialism, and Jewish identity—Marhoefer finds him lacking. Not only is he a white, bourgeois man of the 19th century, but in his publications and correspondence he conveys his sexism and a sense of German cultural superiority. While critical of the racism he encountered in the U.S. and elsewhere, he remained sure of the higher cultural evolution of European men. For similar reasons, Marhoefer criticizes him for portraying Jews as civilized white Europeans while dismissing anti-Semitic racism as merely unscientific, religious irrationality. Hirschfeld’s favorite holiday was Christmas, and, like so many secular Jews who felt thoroughly assimilated into the German bourgeoisie, he refused to be “othered” by Nazi hooligans. (Sigmund Freud, similarly, was so sure he was above Nazi persecution that he resisted entreaties to leave Vienna until after Hitler annexed Austria in 1938.)

Hirschfeld’s religion was science. Scientific knowledge and rationality, he believed, would sweep away the ignorance and prejudice that were the source of racism, homophobia, sexism, and anti-Semitism. His motto and that of the Scientific-humanitarian Committee was “Per scientiam ad justitiam” (through science to justice). He had it engraved on his tomb. Marthoefer’s broader point is that his confidence in the enlightening force of science was misplaced. Even today, biological research on the basis of sexual orientation or the preponderance of medical support for gender-affirming care does not appease anti-LGBT forces.

In addition to her incisive critique of Hirschfeld, Marhoefer excavates the truly forgotten life and work of Li. When he met Hirschfeld in Shanghai, Li was a 24-year-old medical student from a wealthy Hong Kong family. It must have been mutual love at first sight, as Li abandoned his medical studies and family to accompany the senior sexologist on his remaining world travels throughout East Asia, India, the Middle East, and back to Europe. For his part, Hirschfeld was so entranced by the charms and intellect of Li that he anointed him as his successor to the important scientific mission of the Institute. Two months before his death on his birthday (May 14, 1935), Hirschfeld revised his will, leaving his estate jointly to Li and Giese to further Hirschfeld’s sexological research. However, the Institute and its collections had been torched by the Nazis in 1933. Giese had joined Hirschfeld in exile in Paris in 1934 but would be arrested for “public indecency” in a Parisian bathhouse. He was expelled from France after three months in prison. He died by suicide in Brno after the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia.

Li almost disappeared after Hirschfeld’s death. Ralf Dose (director of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society) and Marhoefer are largely responsible for rediscovering the traces of Li’s life. He had returned to medical studies at the University of Zurich two months before Hirschfeld died. Li tried to sustain Hirschfeld’s legacy, but the Nazis had destroyed the Institute. He attended Harvard in the early 1940s but never completed a degree. He seems to have been adrift with his grief. Moving to Washington, D.C., then back to Zurich for fifteen years, then to his native Hong Kong, Li finally settled in Vancouver in 1974. He would have been forgotten after his death in 1993 were it not for utter serendipity: a neighbor retrieved some of his belongings and manuscripts from a dumpster beside his apartment building. Eight years later they made it into the hands of Dose and now reside at the Hirschfeld Society in Berlin.

Marhoefer is perhaps the first scholar to explore these fragmentary manuscripts. She argues that Li continued informal sexological research during his world travels and expounded some of his own theories in his writings. Li seems to have dissented from Hirschfeld’s premise that sexual orientation was congenital. Instead Li wrote: “A homosexual is not born but made” (echoing Simone de Beauvoir’s idea of women’s roles as socially constructed). It was strong bonding to people of the same sex that molded children’s homosexuality (perhaps a projection of his own youthful attachment to Hirschfeld). He also estimated a much higher prevalence of bisexuality, homosexuality, and transness than did his mentor. Marhoefer argues that Li formulated a more fluid theory of gender/sexuality than Hirschfeld’s own. However, she makes clear that these writings from late in his life are a disjointed (perhaps demented) mix of fiction and reportage. Li even endorsed rumors that the Nazis burned the Institute archives to destroy evidence of Nazi homosexuals who had received medical care there.

§

Readers interested in a middle path into the life of Hirschfeld can turn to Brandy Schillace’s The Intermediaries. Her voice is a balance of journalistic and scholarly. She interweaves Hirschfeld’s biography with that of one of his trans patients, Dora Richter (1892–1966), or Dorchen, as Hirschfeld affectionately called her. Schillace’s archival achievement is to piece together the life story of this early trans person who first received sympathetic medical care under Hirschfeld. He also took her in at the Institute as a maid during its last decade. Born Rudolf Richter in 1892 in a small Czech-German village in Bohemia, she lived a hardscrabble life. She struggled with conforming to a male role and wished to alter her body to feminize it. She worked various jobs trying to support her family, at times passing as a young woman. She was only attracted to men and managed to have several boyfriends while leading a double life. At the time, the only word she knew to describe herself was “hermaphrodite.”

Given Schillace’s secondary focus on Dora, her history interweaves the discovery of the “sex hormones” and their early clinical application. Dora was fortunate to have lived during the Weimar period, when there was early research on gender, sexuality, and the biology of “sexual intermediates.” When Dora was first examined at the Institute in 1923, she was diagnosed as a “transvestite … homosexual man”—a sexual intermediary with distinctly feminine features on the binary sexual spectrum. Although the term “transsexual” had yet to be coined, the medical technologies to help trans people like Dora were emerging. Dora had the first of three gender-affirming genital surgeries at the Institute in 1923. In 1930 she had a vaginoplasty. She was able to fulfill her life’s dream of womanly embodiment thanks to one of the few clinics in the world that could help her. Gender-affirming care was controversial at the time, as it has become again despite a century of medical advancements and clinical experience with transgender health.

Hirschfeld’s personal life, wide-ranging studies, and complex political engagements remain foundational knowledge not just for LGBT readers. Hirschfeld’s history draws us into the web of ever-controversial issues on gender, sexuality, racial science, white supremacy, colonialism, and authoritarian fundamentalism. With these three volumes, readers have an opportunity not only to learn about the early foundations of LGBT identities, but also to consider our place in ongoing political struggles.

Vernon Rosario, MD, PhD, is a historian of science and associate clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA.