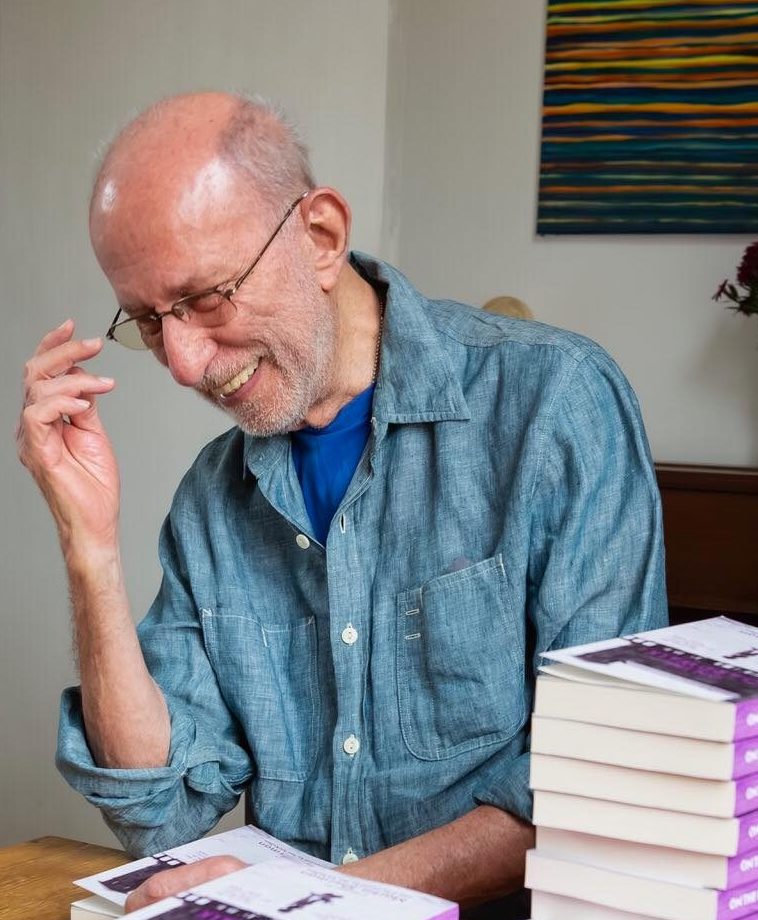

LIKE MANY OF US of a certain age, my life as a young gay man was transformed when I went to Broadway for the first time (at age 21) to see playwright Martin Sherman’s world-changing play Bent. My Jewish boyfriend Peter’s aunt took us to the New Apollo Theater in 1980 to see Richard Gere in Bent as it uncovered the hidden In his memoir On the Boardwalk (Inkandescent), Sherman invites us with incredible humor, frankness, and insight into his journey through the first forty years of his life, including four years in Boston as an undergraduate at Boston University, culminating in the West End and Broadway premieres of Bent in 1979. As Ian McKellen, who starred in the first production in London, writes in his moving foreword to Sherman’s memoir: “His play Bent has educated our world about prejudice and cruelty, and given us one of our most imposing declarations for human rights in dramatic literature.” I caught up with Martin Sherman in June to talk about his wonderful new memoir and the power of theater. Tim Miller: Your memoir is such a total delight, Martin. It seems you were everywhere and worked with everyone, from being at the MLK March on Washington, to Woodstock, to Stonewall, to working with the Bee Gees, Rosalind Russell, Mama Cass Elliott, and Ian McKellen in the premiere production of Bent. You even grew up a few blocks from Walt Whitman’s tomb in Camden, New Jersey! You so beautifully conjure yourself as a Zelig, someone who manages to shape-shift and show up everywhere. Did that archetype help you tell your story? Martin Sherman: I sometimes had a startling life and was present at events in ways that exceeded my station. I stumbled on Stonewall (and had no idea that it was a life-changing event). I went on the March on Washington along with thousands of other people, but only pure fluke led me to actually stand on the platform. I was anonymous but fortunate. I was sometimes in “the room where it happens,” but virtually tripped backwards into it and didn’t at the time feel that I should be there; I felt like an imposter. Years later, looking back, I thought: okay, good for you, but I had to grow into that. During those periods of anonymity, it did allow me to interact with icons like the Bee Gees, Martin Scorsese, Cass Elliot, and the glorious Rosalind Russell, and often in hilarious ways. In retrospective, I’m bemused. How did I get there? TM: On the Boardwalk is so intensely frank and fiercely unflinching around family, self-image, and the body. You wrote so intimately about your mother’s battle with Huntington’s disease and how this hung over your own feeling of mortality for decades. It strikes me as a major heart pulse in your memoir. How did the family history of Huntington’s change your life and your work as a playwright? TM: Your book is the opposite of dreary! Like in your plays, I was so impressed by how deeply you dug and also with such amazing humor and spit-takes. But let me be all lachrymose. I was really struck by how large your hometown of Camden looms in your memoir. Especially since it is the town where Walt Whitman lived the last fifteen years of his life and is buried. Did this proximity to queer history carry any meaning to you growing up?

MS: No meaning whatsoever. There was a hotel in Camden named after Walt Whitman and eventually a bridge, but he was just thought of as some old poet with a long white beard. He was never discussed. In twelve years of public school, I never heard his name mentioned once. No one read his work. As he was basically a non-person, his queerness was not an issue. I had no idea he was queer, but then I had no idea I was either. I basically didn’t know anyone who was queer, not in real life anyway. This was the ’50s, remember. Homosexuality of any kind was never discussed because on the surface it did not exist. Because no one was out of the closet, no one was exactly in it either. There was no closet. It kills me now to know his tomb was relatively close to my house. I always bemoaned the fact that Camden was so gray, an unimportant city where nothing happened. Nothing happened? Edward Carpenter fucked Walt Whitman in Camden! I was sitting in the epicenter of gay American history and didn’t realize it. It’s like growing up now in Liverpool and knowing nothing about the Beatles. history of the Nazi genocide against gay people and both the oppressive and liberatory meaning of the pink triangle. In a fierce play about love, politics, and shameless queer sexuality, Sherman deepened and opened up the sense of what was possible to me as a young queer artist. Indeed, Bent prepared us for the challenges of the AIDS crisis only a little over a year away, and that same pink triangle reclaimed in Bent would soon become the symbol of AIDS activism with ACT UP.

history of the Nazi genocide against gay people and both the oppressive and liberatory meaning of the pink triangle. In a fierce play about love, politics, and shameless queer sexuality, Sherman deepened and opened up the sense of what was possible to me as a young queer artist. Indeed, Bent prepared us for the challenges of the AIDS crisis only a little over a year away, and that same pink triangle reclaimed in Bent would soon become the symbol of AIDS activism with ACT UP.

MS: My family’s history meant I was always existing under a subconscious cloud. I thought I possibly had a gruesome fate in store for me. In an old-fashioned movie, the madcap heroine under a cloud would try to live life to the fullest, thinking every minute might be her last. That’s not exactly how it was with me. Actually, I don’t know how it was. The book is trying to figure it out. It’s all lying there somewhere at the back of your brain. Also, I was caught between my mother’s Huntington’s and my father’s narcissistic complex. God, this book sounds dreary! I promise you it’s not. Remember, it’s a bit rich to write about someone’s narcissism when you are writing a memoir, which is in itself a narcissistic act. I was worried about inheriting my mother’s diseases, but maybe it’s my father’s I got.

TM: Or an LGBT person in 2025 living under Trump not knowing about what the Nazis did to gay people! Uncovering and reclaiming history is so important. It strikes me that another reason why your play Bent is so crucial is how it reclaimed the history of queer people in the Nazi period and what the pink triangle meant. In 2025 how does Bentspeak to us now amid the mess we are in?

MS: As for how Bent speaks to us in the nightmare world we are currently faced with, I suppose it’s not dissimilar—the need to be true to yourself and for that self to have room for others. I can’t say that it means love conquers all, because actually in the play it doesn’t. It doesn’t conquer the outside world, and at the moment the outside world doesn’t even know how to spell love, but rather [the play says]that love can do something magical to your inside, to that elusive thing known as your spirit, and can therefore bring you some form of inner peace—which at the moment is the most we can ask for—and bring you to genuine pride.

TM: Amid all the chaos and complexity of your family dynamic growing up in Camden, what did theater mean for you? Did it save your life? What do you hope readers will glean from this fantastic memoir you have written?

MS: These aren’t easy questions to answer. I wrote the memoir because I felt I had to tell that particular story. Which means I had to get it off my chest. Which means I didn’t imagine anyone reading it. Actually the idea of people reading it is shocking. It means they are entering my private world. But of course I have invited them in. I didn’t realize when I invited them in that they would know almost everything about me. But of course, how could I not have known? And actually it’s not a bad feeling. I’m really old, so my overwhelming attitude is what the hell. And when I finished it, I also realized that it was interesting. And unusual. And worth reading. I suppose what I mainly want people to come away with is the fact that life is constantly surprising and that sometimes things really do get better and that you need to hold on, and hold on, and hold on, and try to somehow know who you are, or at least guess who you are, and honor that. I want people not to give up.

Tim Miller is a writer, performer, and author of A Body in the O.