IN THE TANGLED HISTORY of the horror and panic of the AIDS years, the story of Florida dentist David Acer, who was accused in the early 1990s of infecting several patients with HIV, continues to haunt us. Not since Randy Shilts popularized the now debunked “Patient Zero” theory in his book And the Band Played On had the U.S. media worked itself into such a lather of judgment and scapegoating over a named gay individual. The pitchforks and torches were raised high. At a time like today, when people are being shot in supermarkets for asking someone to wear a mask, we know all too well what this pandemic fever feels like.

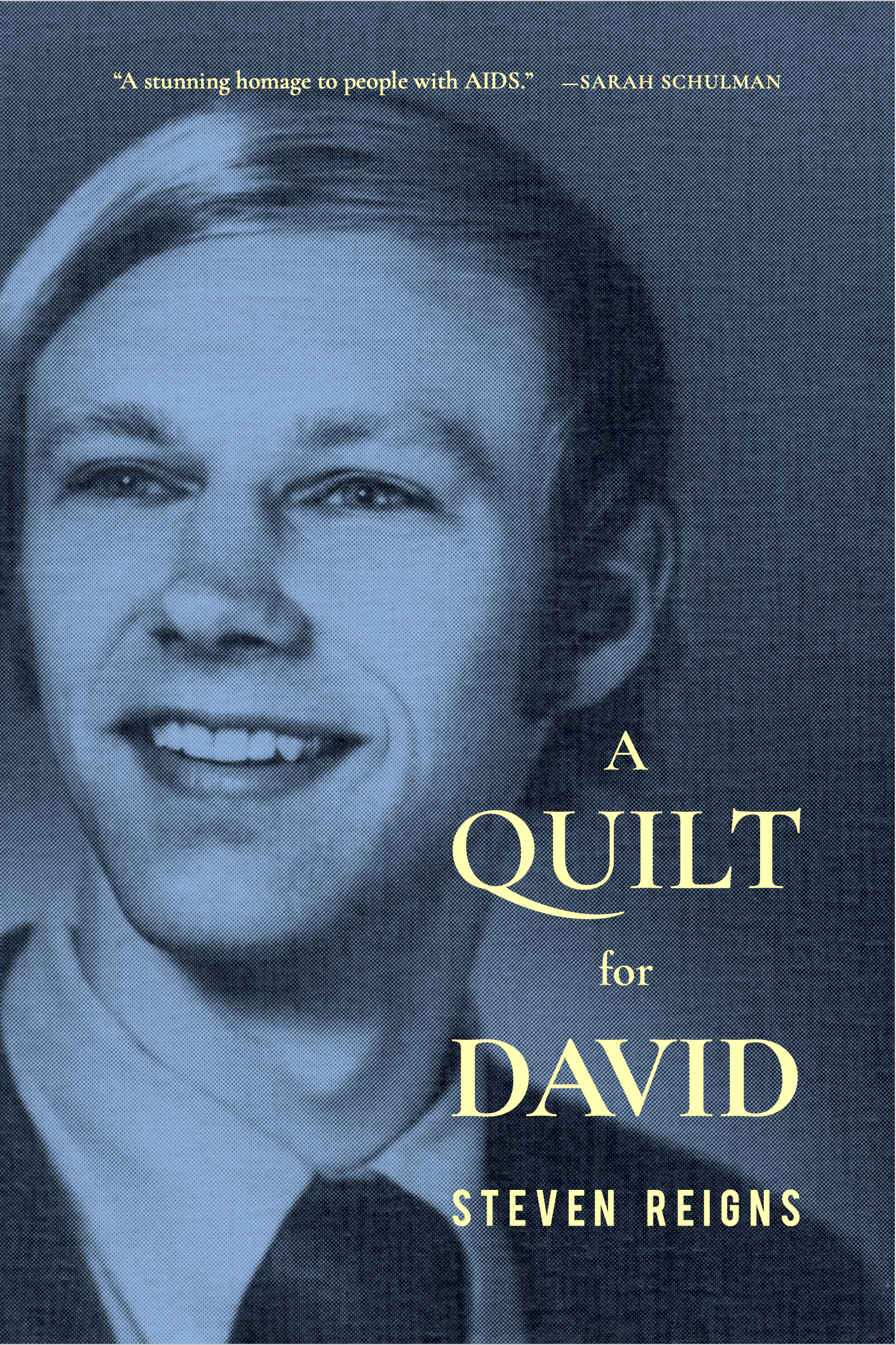

Steven Reigns, the first designated Poet Laureate of West Hollywood, has written a remarkable book of poems that explores this complicated and sad story, A Quilt for David (City Lights Publishers). No stranger to tending the memory, reputation, and indeed the graves of important gay figures, Reigns’ psychologically deft and charged poems sketch a sympathetic portrait of a gay man caught in the terror net during the worst of the AIDS years. Richard Blanco, 2013 Presidential Inaugural Poet, said this of A Quilt for David:

Steven Reigns, the first designated Poet Laureate of West Hollywood, has written a remarkable book of poems that explores this complicated and sad story, A Quilt for David (City Lights Publishers). No stranger to tending the memory, reputation, and indeed the graves of important gay figures, Reigns’ psychologically deft and charged poems sketch a sympathetic portrait of a gay man caught in the terror net during the worst of the AIDS years. Richard Blanco, 2013 Presidential Inaugural Poet, said this of A Quilt for David:

“One of the most important roles a poet can assume is that of emotional histo-rian. Reigns certainly understands that notion in this necessary and genre-bending book.”

Reigns’ book has made me see how often poetry has searched for some kind of “poetic justice” as it interrogates and engages with history and injustice. Oscar Wilde finally delivers his verdict in The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Allen Ginsberg’s Howl pleads the case for Carl Solomon and a generation. Stephen Vincent Benét’s John Brown’s Body puts the Civil War in grim perspective, and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen indicts American racism. This is pretty powerful company to keep, and I wanted to dig into it with poet Steven Reigns.