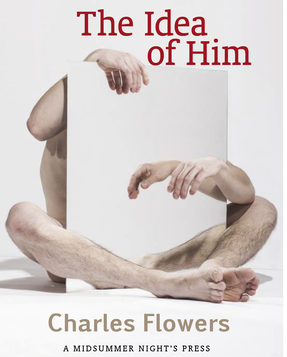

THE IDEA OF HIM

THE IDEA OF HIM

by Charles Flowers

A Midsummer Night’s Press. 60 pages, $16.

I’VE KNOWN Charles Flowers for many years as an editor, but never as a poet. So you can imagine my surprise when I opened his first book of poetry (many years in the making), and discovered poems of such quiet beauty and intense passion, of such unobtrusive mastery and such defiant vulnerability, that I sat slack-jawed in appreciation.

Flowers’ poems are slippery things. They slide so smoothly between memory and dream, fantasy and reality, the present and childhood, that I sometimes didn’t notice the transitions. Nor do I think he wants us to know exactly where we are. All experiences are mixed in the solvent of language or superimposed on each other.

Take his lovely penultimate poem “Easter,” which begins with Flowers and his sister disassembling the home where they grew up because the last surviving parent, their mother, has died.

how some days are sheared by memory,

a mother’s face transfigured by rage and vodka,

the same face, stoic and darkened by tinted glass,

a solitary figure in a boarding lounge,

watching my plane withdraw,

long after she has lost my face

to the rows of windows, yet I can still see her,

face wet from tears, inconsolable & risen.

This one long sentence slips not only between three (perhaps four, if you count the fetus) people, but between various stages of their lives. The mother is “transfigured” by rage and vodka to stoicism and darkness. Her face blurs into his sister—for now both have become “solitary figures in the boarding lounge” watching Flowers’ plane depart. He says that they have “lost his face,” literally, they cannot see him, but also he doesn’t resemble them any longer. The relationship between children changes once the parents have died. The sister has lost the brother she once had, even as she is becoming a mother. But this loss is also a finding: The speaker has found his mother in his sister. When he says “I can still see her,” we do not need to choose which person he sees. He sees all three—mother, sister, and son—in a single “face wet with tears, inconsolable & risen.” All three are inconsolable with grief, and all three are risen: the mother to heaven, the son on takeoff, the sister as her pregnancy progresses. It takes a special skill to find language that can reproduce the slow dissolves and superimposition of this hallucinogenic passage.

At times these unmarked blurring of past and present, one person and another, can be very disturbing. “Wanting” begins as a common enough tale of teenage sex. Flowers gives blowjobs to his shy neighbor, who is “three years older” and regards Flowers “with what seemed like sorrow, though now I’d say he pitied me, for wanting him.” Nevertheless, Flowers desires more than oral sex. He tells us: “[I] wanted him to fuck me like a girl.” Anal penetration presents a problem for the neighbor who, in order to get an erection, needs Flowers to bring in his father’s Playboy magazines. For the neighbor, these introduce women into the fantasy; for Flowers, they introduce his father, which, far from inhibiting him, excites him. He fantasizes clinging to his father’s chest, “my legs wrapped/ above his waist … his cock lifting into me.”

Flowers compares the sexual techniques of his neighbor and his father. Whereas the boy “gasped as he thrust,” the father holds him “in silence, our bodies weaving.” The poem ends not with sexual climax but with a further regression. The speaker recalls his father lifting him as a child onto his shoulders, “my small palms brushing each lintel/ as we walked from room to room.”

The delight with which Flowers writes about his incestuous fantasy is shocking. We have come to associate all such interactions, whether real or imagined, with abuse and trauma. But Flowers makes clear that, although being fucked by his neighbor is painful, “What I remember most was the absence of pain.” The final image of “brushing” against the lintels is startling and surprisingly innocent in its joyousness. Father and son penetrate these various openings of the house’s body. They are not stuck in them. The final image is as much a sign of freedom as it is of containment. Indeed, lintel, derives from the Latin word for limit; Flowers brushes the limits of his pleasure. These are extraordinary poems in which fantasy, dream, memory and the present merge to produce a truth that is powerful, delicious and richly satisfying.

David Bergman is the poetry editor for this magazine.