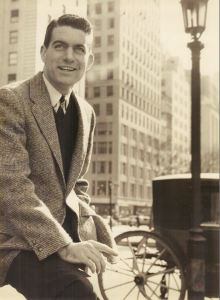

MY LIFE TRAJECTORY took an unexpected tum one sunny October day in 1955 as I was crossing the street at Lexington Avenue and 48th Street in New York. I was taking classes during the day at Columbia University under the GI Bill after four years in the Air Force, and working five nights a week in a Doubleday bookshop.

A voice behind me was shouting “Mister, mister!” In New York you didn’t turn around, even in those relatively peaceful days. I was the object of the voice, however, and the guy turned out to be Burke McHugh, owner of one of the two big modeling agencies that handled men in those days, the other being the Hartford Agency, a toy of A&P heir Huntington Hartford.

A voice behind me was shouting “Mister, mister!” In New York you didn’t turn around, even in those relatively peaceful days. I was the object of the voice, however, and the guy turned out to be Burke McHugh, owner of one of the two big modeling agencies that handled men in those days, the other being the Hartford Agency, a toy of A&P heir Huntington Hartford.

At first I thought Burke was making a pass, but he offered me his card and said I should consider modeling. My ears pricked up when he mentioned a pay rate of $25 per hour, an enormous sum in 1955.

The Burke McHugh agency had a roster of about 75 men and fifty “commercial” girls, as opposed to high fashion girls. Then, as now, women were referred to as girls, men as boys. Commercial girls opened refrigerator doors and, smiling happily, baked cakes in their spotless kitchens, while fashion models adorned the pages of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar dressed in Balenciaga gowns, and worked for Eileen Ford and other agencies specializing in women. Modeling is the only business I know of where women earn more than men. I had to learn the ropes in a relatively brief period of time. If you weren’t making a certain amount of money for the agency after a year, you were shown the door.

High-speed photography did not exist in those days, so you had to hold the pose while the camera clicked. I quickly learned the hard way that your eyes go dead before your smile. One of my first bookings was with a well-known photographer. As a neophyte, I didn’t know what to do with my hands, so I made the mistake of placing one on a hip. He exploded in disgust, “Goddamn it kid, never put your hands on your hips. You’ll look like a fag!” He never booked me again. You sank, swam, or trod water furiously just to stay in the game. It’s a tough, competitive, unforgiving business, and I was learning the tricks of the trade the hard way.

As a professional model you needed a book of eleven-by-fourteen photographs as well as a composite of several of your best shots, along with your vital statistics. Forty regular was the ideal jacket size, and you had to be at least six feet tall. The baptism by fire for newbies like me was the “go see,” when you stood around with about twenty other men who looked like versions of yourself and were inspected by the photographer and his assistants like a prime piece of meat, and eliminated one-by-one for some unexplained defect. Back then, modeling was closed to blacks and anyone else with an ethnic look. The blonds all looked like Tab Hunter and the brunettes like Rory Calhoun. Eventually, when I became well known enough, I didn’t have to suffer cattle calls. The exception was TV commercials.

For my first TV commercial I was paired with the two-time decathlon champion Bob Mathias. I was chosen because I had “good hair” and looked vaguely like Bob. He applied an ill-fated Bristol-Myers product to his perfectly groomed head. My hair was a mess because, of course, I didn’t use the product. The only saving grace was the fact that he was more nervous than I was when the red light on the camera went on. The good thing about commercials was the residuals. You never knew when a check was going to show up in the mail.

Speaking of commercials, and the ubiquitous “casting couch,” I had made a promise to myself that I would never get naked for work. That said, I was booked for a Gillette commercial, which was a big deal, because the residuals could potentially pay the rent for many months. Right after I got the word from my booking agent, I received a call from the account executive at Gillette’s advertising agency inviting me to a cocktail party at his apartment. I made sure I arrived fifteen minutes late, rang his doorbell, and—surprise!—I was ushered into an empty apartment. It was obvious that I was to be the “party.” A pursuit scene ensued straight out of a Marx Brothers comedy, which ended when I pleaded illness and left, sure that I had killed the booking. But no, he was a gentleman.

I was told to let my beard grow for three days for the “before” shot. Stubble is fashionable among models today, but back then “five o’clock shadow” was a faux pas. So I went to Cherry Grove on Fire Island and sat on the beach, making $125 a day while my beard grew. I can remember thinking what a crazy business I had landed in. Back in New York, the “before” segment was shot, at which point I immediately left the studio and paid a visit to Joseph, the famous barber on Park Avenue who catered to models and others who could pay the outrageous price of ten dollars for a haircut. He gave me a shave, and I taxied back to the studio for the “after” part of the commercial, which found me shaving my lathered face with a bladeless razor! So much for truth in advertising.

At about that time lightning struck in the form of a watch ad that I posed for, shot by the well-known photographer Wingate Paine. A beard was affixed to my face, hair by hair. It took two hours, so I made sixty dollars before I even faced the camera. Turned out that I was a dead ringer for Fidel Castro, who was giving dictator Batista fits from the mountains of Cuba. Both Time and Newsweek ran side-by-side photos of Fidel and me in a cap and beard, and The New York Times devoted their entire advertising column to the coincidence. The phones at the agency started ringing off the hook. My fifteen minutes of fame had arrived!

There were not as many male runway shows in those days as there are today. The most important one in New York, sponsored by Esquire magazine. was held at the Waldorf Astoria hotel each year. I walked three of them. A memorable moment was the intermission of the show, when Jayne Mansfield, who was appearing in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? on Broadway, sashayed down the runway in a see-through negligee. Pandemonium broke out! That girl would do anything for publicity in her pre-Hollywood days. I also recall with wry amusement a Brioni show at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC. Ten models from the agency were booked, and every gay man who lived in Georgetown wanted to have the group over for cocktails the night before the show. We all arrived back at the hotel about three a.m. in various states of inebriation. I had a horrendous hangover the following morning; the runway looked like a balance beam. I was afraid of toppling into someone’s scrambled eggs. And the clothes were ridiculous. Everyone looked like Ashley Wilkes and Rhett Butler in ruffled shirts, flowered vests, even buckles on the shoes. But the money was good.

There were not as many male runway shows in those days as there are today. The most important one in New York, sponsored by Esquire magazine. was held at the Waldorf Astoria hotel each year. I walked three of them. A memorable moment was the intermission of the show, when Jayne Mansfield, who was appearing in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? on Broadway, sashayed down the runway in a see-through negligee. Pandemonium broke out! That girl would do anything for publicity in her pre-Hollywood days. I also recall with wry amusement a Brioni show at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC. Ten models from the agency were booked, and every gay man who lived in Georgetown wanted to have the group over for cocktails the night before the show. We all arrived back at the hotel about three a.m. in various states of inebriation. I had a horrendous hangover the following morning; the runway looked like a balance beam. I was afraid of toppling into someone’s scrambled eggs. And the clothes were ridiculous. Everyone looked like Ashley Wilkes and Rhett Butler in ruffled shirts, flowered vests, even buckles on the shoes. But the money was good.

Ah, the money! Where did it all go? In retrospect, I wish I had bought a house on Fire Island when I could have afforded it, but I was too busy leading the high life as a successful model. I received endless invitations to dinners and cocktail parties from people I didn’t know: hosts liked to have models in the room for window dressing. Evenings were often spent drinking in supper clubs like The Lion. The famous “bird circuit” gay bars headed by The Blue Parrot were run by the Mafia in those days. The police were paid off so they would be safe places to gather. I usually went to gay bars with another model or two as a form of protection from “old” lechers, i.e. men over forty. I was always on the lookout for the elusive Mr. Wonderful, and he turned up on the deck of the Sea Shack in Cherry Grove one August evening. That torrid affair turned into a relationship that occupied my life for the next ten years and precipitated my walking away from the business forever.

I had been a journalism major at Columbia before dropping out due to conflicts between modeling and going to class, so I talked my way into a copywriter job at a small advertising agency that paid a fraction of the money I had made as a model. I didn’t mind, as I was in love. Those were my Mad Men years, and I am often asked if the famous TV series was true to life. Yes, it was, but the only thing I had in common with Don Draper was that I drank too much. Eventually, I went to my first AA meeting in early 1971, and I haven’t had an alcoholic drink since. I co-founded a gay AA meeting in San Diego back in the mid-’80s, one that I still attend every week. But I digress.

My friends call me a survivor. I was diagnosed with cancer in 1972, the first major test of my sobriety. I didn’t drink and survived a major operation. The previous year I started up an advertising agency with my former boss, a straight married man, in my New York apartment with a part-time secretary answering the phone. It was a risky move, but one that paid off. John had to commute each day from his home in New Jersey. We freelanced work until we could afford to hire some full-time employees and rent inexpensive office space in midtown Manhattan. It was a grueling schedule of long work days, but ultimately it was worth it. We survived and moved into larger quarters on 42nd Street. When my partner Tom and I decided to move to San Diego in 1979, a move precipitated by my father’s death and my heart disease diagnosis, we had fifty full-time employees.

In 1985, I needed a triple bypass heart operation. By that time my mother was living in a retirement home in La Jolla, and Tom, formerly married with two daughters and a butcher by trade when I met him at a disco, had started a successful antique shop, realizing a lifelong dream. My mother moved into our home briefly to care for me during the crucial weeks after the operation so that Tom could go to work. I’ve had three stents since, the last one in 2006. Everything considered, I’m in good shape today and work out with a personal trainer twice a week.

It would be nice to report that we waltzed into the sunset together, but that was not to be. We did have eight good years before Tom was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. At that time I was serving on the board of directors of Stepping Stone, a drug and alcohol recovery home for gay men and women. Tom’s diagnosis was a death sentence, and for reasons that I will never understand, I tested negative, repeatedly. He died in my arms the morning of January 10, 1990. Certain dates are seared in your brain forever.

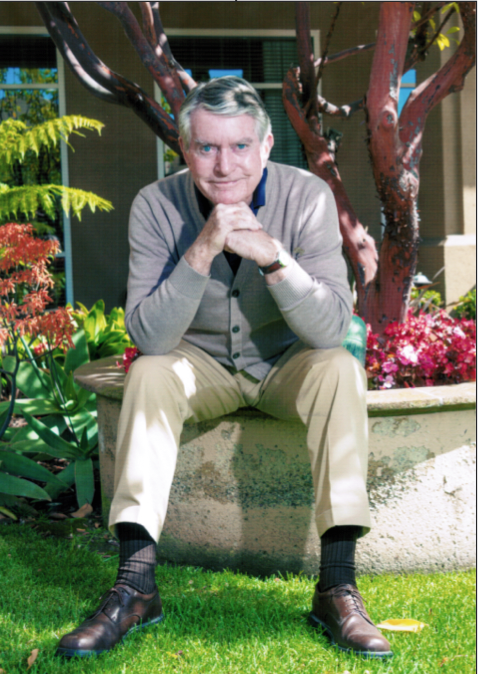

Today I live alone in a nice retirement facility here in San Diego. I have season subscriptions to several different theaters, attend the symphony and the opera regularly. I am a contented 84-year-old, and I rarely look back. Younger friends want to know all about my former life as a model. l prefer to live in the present. Each day is a gift.

Peter Jarman is a retired advertising agency executive living happily in San Diego. He can be contacted at pjarman@san.rr.com.