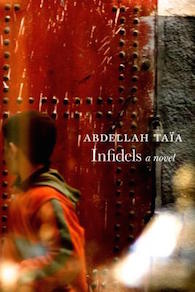

Infidels

Infidels

by Abdellah Taïa

Translated from the French by Alison Strayer

Seven Stories Press. 144 pages, $23.95

A GAY, Moroccan-born novelist and filmmaker, Abdellah Taïa has the distinction of having had his first English-translated book, Salvation Army (L’armée du Salut, 2009), appear with an introduction by Edmund White. “Despite the extreme simplicity and clarity of Taïa’s style,” White wrote, “we sense how sophisticated he is—that this is a simplicity that only intelligence and experience and wide reading in several languages can buy.” Salvation Army’s autobiographical gay themes gave the book—in France and in the U.S.—a particular charge. It was followed in 2012 by An Arab Melancholia (Une mélancolie arabe), also an autobiographical novel.

His third novel, Infidels, feels less like a memoir than do its two predecessors, though significant autobiographical elements remain. The impoverished child-man Jallal lives in poverty in the city of Salé, then in the cosmopolitan city of Cairo, where Taïa did in fact spend time as an adult.

The new novel is told in a series of monologues recounted by its major characters: Slima, a mother and “shamanistic” prostitute whose clients are often affiliated with the Moroccan military; Slima’s mother, who mentors her into the profession of a bridal night introductrice, guiding bride and groom toward a happy outcome on their first night; Jallal, Slima’s adolescent son, pressed by his mother and circumstances into trading sex for favors, who yearns for a life in the trendy neighborhood of Hay Salam in order to flee the disdain of their current Hay Al-Inbiâth neighbors; Mouad, the Belgian turned Muslim who takes up with Slima and “adopts” Jallal.

Threaded lightly through the story is the luminous Marilyn Monroe, whose image on film was indelible to Slima and Jallal as they watched her in River of No Return in two tapes of the movie—one in French, the other in English—given to Jallal by one of Slima’s customers. The movie’s melodramatic triangle of a woman and two men (plus a young boy) on the American frontier indirectly parallels the Taïa family saga, where Slima imagines herself a latter-day reincarnation of the blonde cinema icon.

Taïa was born in Rabat in 1973 and raised in the city of Salé, the next-to-last of nine children in a poor family that spoke only Arabic. He acquired French through determined study and the dream of becoming a filmmaker in Paris, where he now resides. He has become a public French intellectual, although his homosexuality places him in opposition to his Islamic home country, where homosexual acts are punishable by six months to three years in jail. He has been characterized as the first openly gay Moroccan writer, but it’s his status as an exile that has given him this freedom.

There is much to admire in the multiple voices Taïa has created in Infidels, though their voices are not especially distinctive. Throughout these consecutive monologues, we confront that “simplicity” and “clarity of style” that has marked Taïa’s writing from the start. Still, each voice does have a separate attitude and perspective; each claims his or her part of the narrative from a unique vantage point. Occasionally there’s an incantatory quality to the writing, especially in passages most inflected with issues of spiritual quest. If there is a problem in this, it may be that Western readers raised in theological skepticism may find Slima’s conversion to Islam too generalized, too “allegorical.” And it seems a mistake to have this conversion described not by Slima herself but by Mouad. Indeed, the narrative suffers most when the fascinating Slima—besieged by poverty and raising her child alone, but maintaining a proud and imperious disdain for those who judge her a “dirty woman”—is no longer the central focus.

The young adult Jallal’s experience in Brussels takes over in the final sections of the novel, and his turn to fanaticism occurs under circumstances not sufficiently detailed to lend the denouement the force of tragedy—either for him or his victims. Here, Taïa’s restrained language seems to fail either as allegory or as realistic description. The adolescent Jallal is a more urgent and individualized character than the adult Jallal, whose attachment to Mahmoud seems more like a Platonic ideal than a real friendship.

Infidels is perhaps best read after being introduced to Taïa’s earlier work in translation. In its multiple first-person voices, Taïa has certainly moved into new and challenging narrative territory. Like his previous work, Infidels is short and austere. He has created in Slima a memorable woman, neither a victim nor exactly a martyr. She is a force, seeking salvation on her own terms.

________________________________________________________

Allen Ellenzweig is a frequent contributor to these pages.