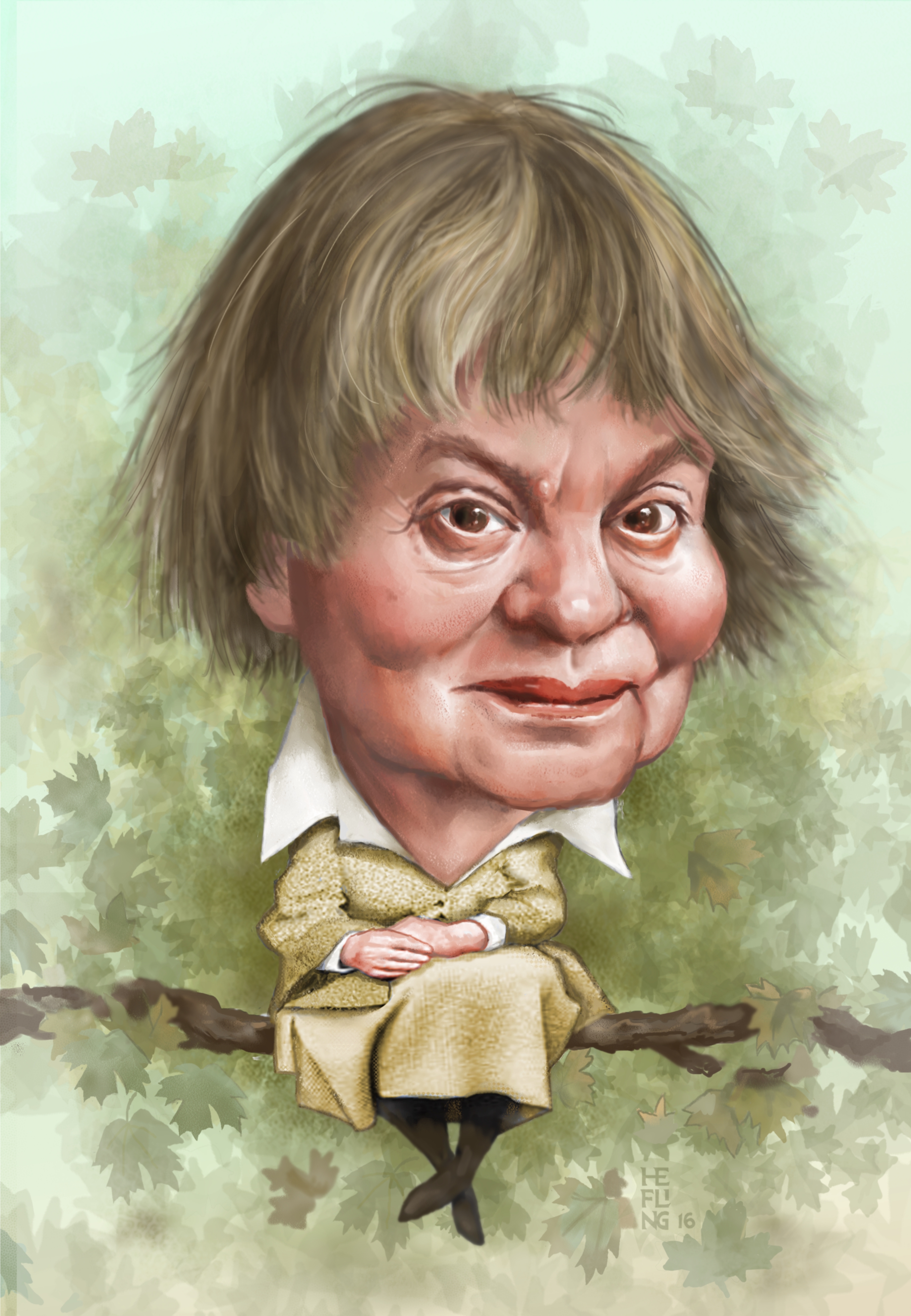

Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch, 1934-1995

Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch, 1934-1995

Edited by Avril Horner and Anne Rowe

Princeton University Press

680 pages, $39.95

IRIS MURDOCH has been hailed as one of the 20th century’s greatest writers, and this collection of her letters demonstrates that this is not hyperbole. The editors have done readers a great service by bringing together a revealing collection of 760 of Dame Iris’ letters. (She was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1987.) Living on Paper opens with Murdoch’s formative years as a schoolgirl in Ireland and closes with her last coherent letters before dementia set in and forced her into a nursing home in Oxfordshire, where she died in 1999. (Full disclosure: I had brief contact with one of the editors when researching my biography of Romaine Brooks.)

Many younger readers may know about Murdoch only from the 2001 film Iris, which was based on two memoirs by her husband John Bayley. Covering the whole span of her adult life, the biopic starred Kate Winslet as the young Murdoch and Judi Dench as the aging writer. What this eye-opening collection of letters does is to give us a fuller picture of an extraordinary person who led a passionately intense and painfully complex life. They reveal a woman negotiating life’s minefields and grappling with the ethical quandaries of everyday life, which she approached in anything but a thoughtless or knee-jerk way.

I have read more than three-quarters of Murdoch’s 27 novels and many of her philosophical essays. Her reflections on morals, ethics, art, and love have shaped my own writing and criticism. I was captivated by her intellect and her emotional intensity from the moment I discovered her writings in my mid-twenties. Every one her novels is a fascinating study on life, love, and the messiness of living passionately. My personal favorites include A Severed Head; A Fairly Honourable Defeat; The Black Prince; The Sea, The Sea; Under the Net; and, at the top of the list, Nuns and Soldiers.

Murdoch’s understanding of her bisexuality evolved over time, as the letters demonstrate. She struggled to understand the nature of her sexuality, finally acknowledging her same-sex desire—and acting on it with gusto. Her sexuality was as ample and baroque as the rest of her life. In May 1964 she wrote a most striking letter to her then lover Brigid Brophy: “I suspect that part of the difficulty with you is that you are not a true classical sadomasochist like me. You are just an abnormal perverted one. Or not one at all.” Few among us would have the courage or the insight to describe our own psychology so unsparingly.

Murdoch’s understanding of her bisexuality evolved over time, as the letters demonstrate. She struggled to understand the nature of her sexuality, finally acknowledging her same-sex desire—and acting on it with gusto. Her sexuality was as ample and baroque as the rest of her life. In May 1964 she wrote a most striking letter to her then lover Brigid Brophy: “I suspect that part of the difficulty with you is that you are not a true classical sadomasochist like me. You are just an abnormal perverted one. Or not one at all.” Few among us would have the courage or the insight to describe our own psychology so unsparingly.

What the letters reveal most strikingly is the breadth and depth of Dame Iris’ intellect: her curiosity and questioning mindset. Words meant everything to her, remarked John Bayley. So did her friends, and among the many who make an appearance here are Brigid Brophy, Elias Canetti, Raymond Queneau, and Philippa Foot. They bore witness to Murdoch’s emotional hunger, her tendency to push the limits of what was socially acceptable, and her edgy humor. She could be difficult, of that there’s little doubt. She was attractive, moody, and obsessive, and her complicated sex life inevitably left some wreckage in its wake. But she was also kind, generous, caring, and unfailingly loyal to her friends.

In her two dozen novels, Murdoch explored the mysteriousness of other people, mindful that no matter how well we think we know someone, there are always secrets of the self that we cannot reach. Always surprising, Murdoch’s characters rarely just react to the circumstances thrown at them. Instead, they contemplate possible courses of action from various angles and consider their possible moral and practical consequences.

Murdoch was well aware that she was beginning to suffer from bouts of forgetfulness. In Living on Paper we bear witness to the looming calamity of Alzheimer’s: of a brilliant mind that finally lost its last battle and migrated to a space where no one could follow her. One of her last coherent letters (September 1995), to Lucy Klatschko, who had entered a convent back in 1952, closes poignantly with the words: “please forgive me for all this stumbling.” It’s hard to imagine the bewilderment, the sense of being utterly lost in a vast emptiness, that she must have experienced—a brilliant mind reaching the end of the known world. In 1999, Dame Iris Murdoch died at Vail House nursing home, and so was lost one of the last century’s greatest writers in the English language.

Cassandra Langer is the author of Romaine Brooks: A Life, about which she is interviewed in this issue.