ESTHER PRESSOIR

ESTHER PRESSOIR

A Modern Woman’s Painter

by Suzanne M. Scanlan

Lund Humphries. 154 pages, $44.99

SUZANNE M. SCANLAN, a professor at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), was searching for a topic she could develop into a book. While digging into the RISD archives, she made an exciting find: a heretofore unrecognized RISD graduate who had earned her living from her art, exhibited her work throughout her life, and was, Scanlan discovered, a lesbian. The result is her illustrated biography Esther Pressoir: A Modern Woman’s Painter.

Later in the 1920s, she attended the Art Students League in Manhattan, and on a dare went off to Europe for seven months (usually accompanied by a woman friend who may have been a lover), bicycling across northwestern France and southern Italy, making almost daily trips to American Express offices to send work home and collect art supplies that she’d arranged to have sent. The work sent home included her journals, filled with sketches and narrative, which were carefully saved by family members. (On her death, her studio was notable for being “packed to the gills” with her work.) She worked incessantly, depicting street life, beach scenes, men drinking in saloons, elderly ladies gossiping, as can be seen in full-color plates in the book. She seems never to have gotten into any major difficulties or harrowing situations, other than constant bicycle breakdowns (she cycled in skirts and heels).

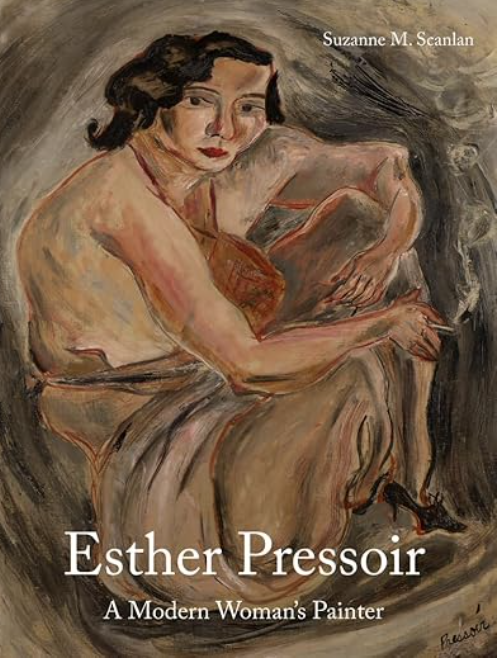

On her return from Europe, she married a man named Frederick Payne, but they quickly divorced. After she settled in New York, Pressoir had several female muses. One of the most intriguing, and about whom little is known, was a woman named Florita, who lived in Harlem and may have been a dancer. She is featured in many of Pressoir’s works and, like so many of the women Pressoir portrayed, is shown nude or semi-nude, dressing or undressing, or taking a bath. There is a 1930 watercolor of Florita’s head in which she’s shown with a modern hairstyle, heavy green beads encircling an elongated neck, and an enigmatic smile. But in many instances, Pressoir’s women were not conventionally beautiful.

Many of her works are scattered in private collections, but the RISD Museum has a growing collection, and a large number of her works are held at the Ingeborg Gallery in Northfield, Massachusetts. “Straddling representation and abstraction,” in Scanlan’s words, Pressoir made a secure living in her later years as a spot illustrator for The New Yorker.

Esther Pressoir is both an engrossing biography, with its roots in serious research, and a beautifully illustrated art book. It showcases the many modes in which Pressoir worked: lithography, etchings, linocuts, scratchboard, watercolors, oils, and more. In her later years, she made ceramics and silver jewelry. Her sense of humor is evident in a 1945 ceramic bowl titled Abduction of Europa by Zeus, on which she’s painted an insouciant blonde nude who could have come out of the pages of Playboy magazine, lolling atop a bull.