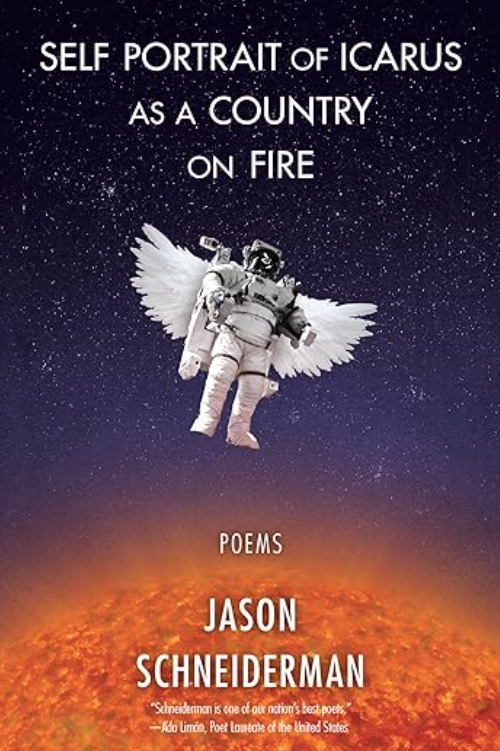

SELF PORTRAIT OF ICARUS

SELF PORTRAIT OF ICARUS

AS A COUNTRY ON FIRE

by Jason Schneiderman

Red Hen Press. 80 pages, $17.95

AS A POET AGES, he’s often faced with several choices. He can keep doing what he has always done, or he can, by seriously confronting himself, seek another voice. Jason Schneiderman has done the latter brilliantly in his new book, Self Portrait of Icarus as a Country on Fire. He reflects humorously on his life as a poet, often poking fun at himself and his poses. He wrestles with his Jewish heritage by taking on Stalin and the Holocaust, and then delves into the angst of gay divorce.

His long lines and breezy casualness make you feel you’re in a café where, after a few drinks, the poet has unlatched the cages in his imagination, freeing the wild creatures that reside there. In the poem “Catastrophist,” he starts by speaking to the reader: “Your heart doesn’t have to break every day.” You feel as if he’s leaned over the table to explain what he means. “Most of life, if you are lucky, is pretty boring,/ filled with unburned houses,/ uncrashed cars,/ unsick friends, unfled countries,/ and unshot schools.” He goes on to imagine a tribe that most values those who can create fear and caution. But, with a quick shift, he admits that his dreaded fears rarely happen and that he’s stuck with the fact that “It’s not easy to live just one life, and yet/ we are called upon to do just that.”

You feel as if he’s led you into seeing the world from four or five different directions and managed to bring you back to something substantial, worth remembering. In his Stalin poems, he draws our attention to our own demagogues and to how they operate: “Do you know what’s persuasive?/ Repetition./ You just have to say it over and over/ and people will be pretty sure/ it must be true.” What’s refreshing is that his poems do as Robert Frost said they should do: start with delight and end with wisdom. His insights are so refreshing that you want to laugh and, equally, to grimace, because they’re so graphically on target. He’s willing to take on the white supremacist coopting of the Nazi racist term “Blood and Soil” and express his fierce rage: “I think Someone should blow out all/ their big, stupid candles./ If all you want is dirt,/ it’s everywhere you go.” He makes the political personal, speaks the truth with irony, and admits his own vulnerability all at once.

When he shifts to his divorce, a topic fraught with potential self-pity, he steps back to make seemingly agonizing moments both funny and sad. When speaking about returning to his once-shared queen-sized bed, he ponders where to place his pillow, and what to do with his former partner’s pillow, then shifts to say: “If you would like this/ to be a metaphor,/ I won’t mind./ Here I am, figuring out how/ to take up all the space/ I used to share.”

In his last poem, dedicated to his mentor and friend Stanley Plumly, he says: “I’ve never made sense of my life.” Yet his modesty reflects what is most endearing about him. He can shift from painting a room to pornography, to stories about Plumly, to Boy Scouts, to a doctor doing a rectal exam, and to himself, mourning his friend, and he never stops wanting to find how all of this makes up his life. He never tires of asking questions about what he or any gay man must do to make sense of his life. No wonder he ends his book with these lines, which speak to what it means to be alive: “I feared I’d never fully make sense,/ even to myself, but how it reassured me, that as long as someone/ knew how to live, it would be ok if I never quite figured it out.”

_______________________________________________________

Bruce Spang is a poet and writer living in Chandler, NC.