AT THE PEAK of his vitality, age 38, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was sojourning in Genoa, Italy. He cruised the sandy shores in white slacks, a healthy tan, and a Panama hat. Back in his hotel, he wrote in his notebook: “[I am] experiencing a menacing, heart-rending attack of desire and savage, pent-up surges of emotion … moments of sudden madness when the lonely man embraces the first man to come his way and treat him as a precious gift from heaven.”

Apparently this reclusive man of letters was not shy about sharing such “surges of emotion” with several men with whom he shared a deep and abiding intimacy. To his old friend Paul Ree, Nietzsche wrote about himself: “You could have seen a man leaping up and down in the room like a satyr, waving his arms around like one possessed. … I had a kind of unrequited love for you.” And to childhood chum Erwin Rohde: “It fills me with profound dissatisfaction that we cannot live together. We are virtuosi on an instrument that other men cannot and will not listen to but which is for us the source of the greatest enchantment.” In unpacking what is meant by “instrument” and whence the “source” of the “greatest enchantment” derives, I can’t help but wonder: Was Nietzsche dropping hair pins—was he gay?

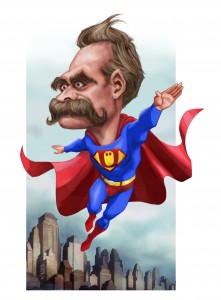

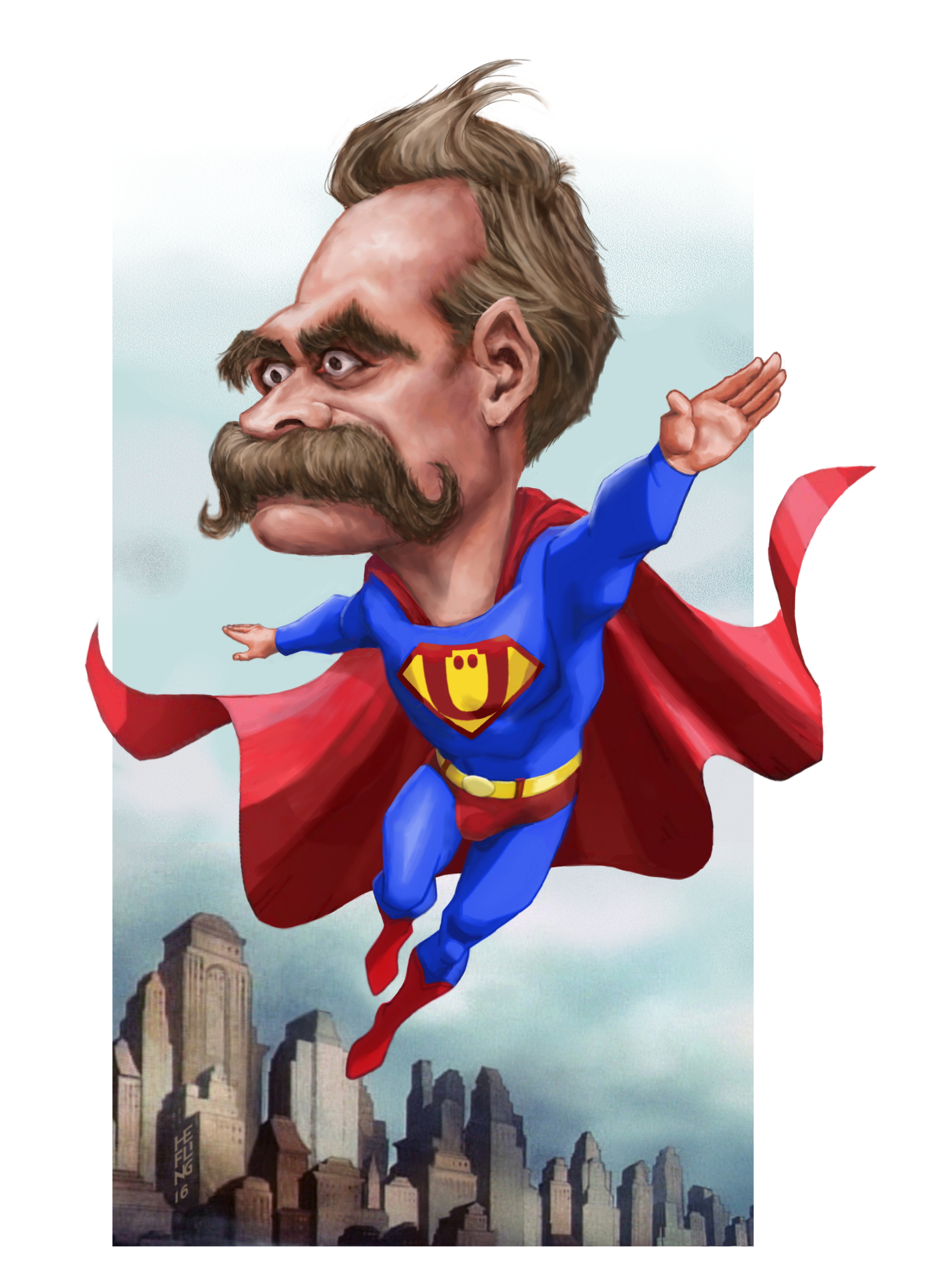

While most scholars tell the “straight” story of Nietzsche, which often includes him contracting syphilis in a heterosexual brothel, numerous wink-winks abound in his own work: “Is it any wonder that we ‘free spirits,’” he writes, “are not exactly the most communicative spirits?” But for all these intimations, mainstream scholars have not been inclined to unveil him. In fact, when most people think about Nietzsche, the first thing that comes to mind is probably not the possibility that he might have been a homosexual. Instead, he is known for proclaiming the “death of God” and even supposedly for being a proto-Nazi and an anti-Semite, sporting an overgrown walrus mustache.

For somewhat more serious students, he is frequently remembered as the first Western philosopher to break with Christian and Platonic values that would ensconce “truth” in some spiritual or ideal realm unattainable to the vast majority of us stumbling about in sin or in a cave. He called for a revolutionary “transvaluation of values” through which our deepest passions and most devilish instinctual drives could be transformed into a newly personal and sovereign morality, what he called “the great Yes to life.”

For somewhat more serious students, he is frequently remembered as the first Western philosopher to break with Christian and Platonic values that would ensconce “truth” in some spiritual or ideal realm unattainable to the vast majority of us stumbling about in sin or in a cave. He called for a revolutionary “transvaluation of values” through which our deepest passions and most devilish instinctual drives could be transformed into a newly personal and sovereign morality, what he called “the great Yes to life.”

Nietzsche anticipated both the idea of unconscious motivation later advanced by Freud and the alchemical process of dialoging with the demonic persons of the psyche, a central tenant of Jungian thought. He is also considered to be a major founder of existentialism: “What does your conscience say?—‘You shall become the person you are.’” Anticipating postmodern philosophy, he asserted that “there are no moral phenomena at all, but only a moral interpretation of phenomena.” Third Wave Feminists value his assertion that the “Will to Power” must be tamed by a humanizing principle.

I fell in love with Nietzsche as a lonely gay teenager, living with my Jewish parents in the Bronx, because he honored close male friendships, celebrated the body beautiful, devalued biological breeding, and called for people to love their fate (“amor fati”), and “live dangerously” rather than wallow in hapless victimhood. I took to reading Nietzsche’s psychedelic philosophical novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra, his first attempt to present his whole philosophy, because I found the quirky, trippy work as stirring as the countercultural texts by Carlos Castañeda and Hermann Hesse, but more sexually alluring. I developed a crush on the fantastic figure of the “overman,” the evolutionary answer to the death of god, offering human beings the chance to “overcome” their primitive state by longing for this heroic figure—how gay is that?

I was not the only one wondering if Nietzsche was a homosexual. I would eventually learn that certain key cultural figures, including Freud, Jung, and Foucault, strongly attributed Nietzsche’s courage and brilliance to his being gay. Even Walter Kaufmann, the American scholar who situated Nietzsche as among the greatest minds in Western thought in his book Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist (1950), could not help but wonder aloud about the sexuality of this bad-boy philosopher. Countering charges of Nazism, Kaufmann showed that Nietzsche loathed German nationalism, detested ideas of the master race, and often idealized the Jews. So it’s refreshing to see the researcher most credited with having rehabilitated Nietzsche having a little fun when commenting on his translation of Nietzsche’s The Gay Science: “It is no accident that the homosexuals as well as Nietzsche opted for ‘gay’ rather than ‘cheerful.’ ‘Gay Science,’ unlike ‘cheerful science,’ has overtones of light-hearted defiance of convention; it suggests Nietzsche’s ‘immoralism’ and his ‘reevaluation of values.’”

One of the richest analyses of Nietzsche’s homosexuality comes from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who writes in her Epistemology of the Closet (1990) that “many of Nietzsche’s most effective intensities of both life and writing were directed toward other men and toward the male body,” and that “Nietzsche offers writing of an open, Whitmanlike seductiveness, some of the loveliest there is, about the joining of men with men.”

A new generation of Nietzsche scholars has gone even further as we gain greater access to Nietzsche’s previously unpublished materials. Key examples include Joachim Köhler, who wrote Zarathustra’s Secret (2002), the first gay-affirmative biography of Nietzsche, and C. Heike Schotten, who wrote Nietzsche’s Revolution: Decadence, Politics and Sexuality (2009), the first extended work to equate Nietzsche’s “transvaluation” with being queer, as well as Charles Stone, who contributed a piece to these pages in 2002 about how Nietzsche’s “Death of God” idea paved the way for the philosophy of Gay Liberation: “The institution of the Christian religion has been the primary oppressor of those persons in the West who love members of the same sex,” and the death of the Christian god directly challenges the power behind that oppressive force. These gay-affirmative readings allow for a reconstruction of Nietzsche’s life and a new way to understand his works.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE was born in 1844 in the Prussian village of Röcken, near Leipzig. His Lutheran pastor father died from a brain ailment when Nietzsche was five, but not before frequently beating Nietzsche and his sister, Elisabeth, while going insane. The mother insisted that Nietzsche act like an adult at all times. “What a poisonous atmosphere I had to breathe when I was a boy!” he later lamented. He suffered terrible nightmares all his life.

In 1858, Nietzsche was admitted to Schulpforta, Germany’s venerable Protestant boys’ boarding school. He thrived there until 1864, making enduring friendships with boys who would also become well-known thinkers, including Erwin Rohde, a Classical scholar. In 1862, he wrote to his mother with exciting news: he was going to recite one of his poems in the school’s annual show. But the poem turned out to involve a very untypical story, presenting the love affair between a boy and his father in which “the old man begins to waver, his eye becomes cloudy/ He grasps his son’s hand and holds it tight/ And covers his face with kisses.” The son is stricken and gives “One last kiss” as his father breathes his last ecstatic gasp in the boy’s arms.

This is also the time when Nietzsche, influenced by Byron’s bisexuality, wrote a manual on masturbation titled “Euphorion” and sent it to another student with whom he had fallen in love. And when a certain fair youth, Guido Meyer, had been expelled due to a drunken orgy, a bereft Nietzsche wrote him an ode, quoting from Sappho: “Eros shatters my mind once again.” He rhapsodized his beloved as a marble Dionysus, “leaning gently backwards,” evoking in Nietzsche’s “glowing heart” the “glorious dance of spring,” planting “fresh blossoms” that “would continue to spring forth from thee!”

The male-oriented education at Schulpforta inspired Nietzsche to reject his mother’s preferred path of theology and instead become a Classical scholar. In recognition of his genius, Nietzsche was given a professorship at the University of Basel when he was only 24. During this time he idealized German composer Richard Wagner, but soon became disgusted with Wagner’s Germanic nationalism and anti-Semitism—and, I imagine, his homophobia! The overbearing Wagner had the audacity to write to Nietzsche’s doctor, Otto Eiser, expressing fears related to Nietzsche’s excessive masturbation and tendency to hang out exclusively with men. In writing to his lifelong secretary Peter Gast, Nietzsche acted affronted by the composer’s accusations, writing that “Wagner is full of spiteful tricks.” This incident suggests that Nietzsche understandably felt pressure to remain in the closet, as did virtually everyone at that time.

Nietzsche became a star professor, with students crowding into his lectures on Achilles’ shining shield of glory, among many other Classical subjects. His first book, The Birth of Tragedy, concerned the connection between the gods Apollo (reason) and Dionysus (passion), which gave birth to a new consciousness and to an art form, Greek tragedy. Yet the nightmares, migraines, and insomnia he had been suffering all his life grew unbearable. He had no choice but to resign from the university system in 1879, whereupon he would become a wanderer and a radical philosopher, “free from all constraints such as those of marriage and position,” a situation that lasted until 1889, when he experienced a mental collapse that silenced him for the rest of his life.

Because Nietzsche usually traveled anonymously, conventional scholars have been befuddled as to what he was doing, grasping onto the few crumbs available to argue for Nietzsche’s presumed heterosexuality. In 1882, while touring with the handsome Paul Ree in Rome, Nietzsche met up with Lou von Salome, the precocious 21-year old daughter of a Russian general in whom Nietzsche found a kindred spirit. He hastily proposed marriage to Salome, which would end up as a kind of ménage à trois with Ree and Salome, but he experienced rejection by both. It seems likely that Salome was what we might call Nietzsche’s gay “sister” in whom he confided his secrets, rather than a sexual love interest. Salome apparently had been one person who discussed Nietzsche’s “secret room,” his “dungeon of hidden nooks and crannies.” Years later, when she was an influential intellectual, she wrote: “To the extent that cruel people are also masochists, the whole situation also has a relevance to the question of bisexuality—a phenomenon of profound significance. The first person I talked with about this matter was Nietzsche—himself a sadomasochist.”

Of course, being into S/M doesn’t necessarily make a person gay. But if Nietzsche were into S/M, that might help explain some of his most challenging ideas, including the discussion of master-slave dynamics in The Genealogy of Morals. “Every great philosophy,” he tells us, “[has]so far been … the personal confession of its author, a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir.”

What we are learning now is that Nietzsche came to know the whole Mediterranean coastline around Genoa, writing that the move there was “the happiest move I have ever made.” He dubbed himself as the “New Columbus,” perhaps because he was discovering the New World of the homosexual body, the truest “terra incognita” in a homophobic world. Here he was utterly transformed from a sickly nerd to a fairly robust man enthralled by “a magical sensation of affinity and similarity with others in appearance and desire, a relaxation in the confidence of friendships, a shared blindness without suspicion or reservation.” Morality and duty were replaced by “a thrusting rebellious desire to take to the open,” to joyfully experience “an act of desecration” where the “soul would be overcome with a flush of shame at what it had just done,” while at the same time to “rejoice that it had done it,” and enjoying an “intoxicating feeling of jubilant terror that brings with it the assurance of victory.”

While in Genoa, Nietzsche experienced for the first time a soothing balm for his suffering, what he called “a great release.” He wrote a poem about something that happened “last night” when two men slept so soundly together in a boat: “Morning came. On the dark depth/ lay a barque, resting, resting/ What is happening?—thus the cries went up/ The cries of almost a hundred: What’s there? Blood? Nothing was happening! We were asleep, all asleep/ Ah, how good it was, how good!” It is no wonder that during this miraculous recovery Nietzsche had a vision of a great teacher, whom he would call “Zarathustra,” and an apparition of a vital, evolved person, which he would call Übermensch or “overman.”

OF COURSE, there is no surefire proof that Nietzsche was homosexual. To apply such a label would risk what postmodernism calls an “anachronistic” reading. All the same, I imagine that readers can now get a sense, in learning about his life, that he may have been a person with strong same-sex-loving inclinations.

With such an understanding, we might begin to review his work in a fresh way, paying special attention to his visionary yearning for the advent of the overman, a concept considered by most scholars to be the central organizing principle of Nietzsche’s œuvre, where “man” occupies a position between the ape and the overman such that his evolutionary goal in self-becoming has only just begun. Kaufmann clarifies that the term “over” is crucial in understanding the overman: “What is called for is not a super-brute but a human being who has created for himself that unique position in the cosmos which the Bible considered his divine birthright.” The meaning of life, he adds, is found “in the few human beings who raise themselves above the all-too-human mass.” The only path towards this “freeing” of the individual can come through “going under,” which has analogies to the ancient Greek notion of the descent into the underworld to gain new initiatory life.

In Zarathustra, we meet the eponymous “wise old man” who, having lived in solitude for the last ten years, is now prepared to share his ripening knowledge. Zarathustra descends from the mountain to tell the people that “God is dead” and that the wonderful “overman” will come to bring new meaning to the earth. He intones eighteen blessings about anyone who would “go under” to realize the overman. At first Zarathustra is mocked by the collective. But soon loyal “brothers” gather to learn of the new task: “You shall build over and beyond yourself, but first you must be built yourself.” Having initiated them with his “gift-giving virtue,” he takes leave of his beloved brothers under a rainbow, predicting that their creative efforts will found a new species of people who will be the destroyers of old values and the creators of new “tablets.”

Nietzsche’s descriptions of the rise of the overman and of Zarathustra’s disciples seem infused with so many intimations of male-male intimacy and mutuality, not to mention a rainbow! These qualities of Nietzsche’s central vision call to mind psychologist Mitch Walker’s evocation of the archetypal double as a living “soul-figure” potentially inside of each gay man’s psyche, an inner partner of intense warmth, longing, reciprocity, relatedness, strength, empathy, and erotic initiation beckoning us forward into greater self-realizing vitality and wholeness. Walker’s more overtly gay-affirmative psychological approach can, it seems to me, help us to appreciate Nietzsche’s overman not as some future evolutionary achievement but as a living erotic presence within gay psyche right now. He is, no doubt, the source of the alpha stud fantasy many of us gay men yearn for in the outer world of romance and sex. Ideally, he can be apprehended as a real being within, if one but tries to look inside.

Sadly, Nietzsche ultimately failed in his own quest, perhaps because, as Jung suggested, the rebellious philosopher went mad by over-identifying with the overman. But today we have the psychological tools to move Nietzsche’s queer dream forward. “Wake up and listen,” Zarathustra says. “You that are withdrawing, you shall one day be the people: out of you, who have chosen yourselves, there shall grow a chosen people—and out of them, the overman. Verily the earth shall yet become a site of recovery. And even now a new fragrance surrounds it, bringing salvation—and a new hope.”

With the fate of the earth now hanging by a thread due to human violence and greed, I hope these preliminary gay-affirmative speculations can promote a discourse that invites gay people today to cultivate their radical nature in the face of attacks against the revolutionary value of same-sex love. With this appreciation, gay men can be seen as not only children of Edward Carpenter, Walt Whitman, and Karl Ulrichs, but also of that philosopher-cum-psychologist Friedrich Nietzsche, who hoped his words would inspire unusual people like himself to become “brave companions” of “free will” and engage the epochal work of building a new world: “I see them already coming, slowly, slowly, and perhaps I shall do something to speed their coming if I describe in advance what vicissitudes, upon what paths, I see them coming.”

Douglas Sadownick, PhD, a founding member of the Institute for Uranian Psychoanalysis, wrote his 2006 dissertation on a gay-affirmative reading of Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Discussion1 Comment

What do you think of Martin Heidegger’s confession that it was while reading Nietzsche that he decided to become a Nazi?