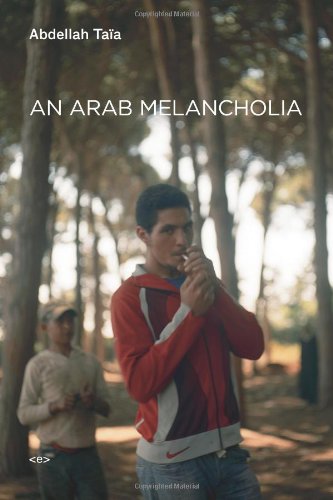

An Arab Melancholia

An Arab Melancholia

by Abdellah Taïa

Semiotext(e). 144 pages, $14.95

THE WRITINGS of Abdellah Taïa, who positions himself as the “first openly gay autobiographical writer” published in Morocco, clearly transgress the religious customs of his native country. An Arab Melancholia forms part of this larger project as it traces several unrequited love affairs spanning three countries on two continents.

An Arab Melancholia lives up to its title. Nostalgia permeates the texture of the writing, at times bordering on the self-absorbed pathos of the romanticism of Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Taïa’s style oscillates between minimalist and expansive. The multiple journeys of the narrator accentuate the feeling of uprootedness as he moves from Morocco to France to Egypt, his travels mirroring the internal strife of Taïa. He describes Paris as his home for seven years: “the place where I tried to discover who I was, tried to endlessly reinvent myself.” But “France wasn’t all it was supposed to be. Every day, he was in for another letdown. Disappointment had to happen.” (The shift from the subjective “I” to the third person “he” emphasizes the narrator’s sense of alienation in the City of Lights.) More poetic flights happen in Cairo, which fits him like a glove, and is described as “A Turkish bathhouse with 20 million bathers. A human monster. A blue flower, beautiful and covered with dust. An inspiring, stifling desert.”

A quick reading might leave the impression of a facile coming-of-age story rehashing age-old themes in tales of self-discovery—unrequited love, poor self-image, family strains. However, Taïa tests the limits of the autobiographical genre, questioning the relationship between the real and the fictional: “Yes, that was me, the me of fiction, the me of reality.” Furthermore, he construes the act of writing as a path to freedom and self-definition. The Arabic language becomes “a space of origins” with which he will dare “to talk about everything, reveal everything and one day, write about everything, everything. Even forbidden love. And call it by a new name. A name that had dignity.” It is worth noting that Taïa has chosen to write in French rather than in Arabic, leaving us to wonder whether Arabic lacks the linguistic tools to engage with queer identities or whether the colonial language still defines its subjects. In the end, however, the choice of French might have just imposed itself as a language with a wider readership, thus allowing Taïa Abdellah to reach a larger audience.

This decision does not, however, undermine the political importance of the book, which offers a political commentary in the guise of a personal quest. Ironically, the novel was published in 2008, three years before the Arab Spring blossomed across North Africa and the Middle East. The following lines from the book gain new meaning in the post-Mubarak era: “I was in the heart of the Arab world [Cairo], a world that when you came down to it, no longer believed in anything. .. A world that never tired of making the same mistakes over and over again, and blaming someone else each and every time. The West, the West, it was all their fault!” Abdellah Taïa has already been the target of violence and censorship: a conference near Casablanca about his work had to be canceled due to pressure from Islamist groups inside Morocco in May of 2012. Despite these setbacks, the author remains optimistic, as reported in the French gay magazine Têtu, where he reiterated his confidence for an Arab Spring flourishing into a full-fledged recognition of GLBT rights.