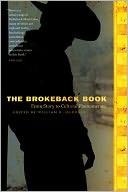

The Brokeback Book: From Story to Cultural Phenomenon

The Brokeback Book: From Story to Cultural Phenomenon

Edited by William R. Handley

University of Nebraska Press. 386 pages, $24.95

I CONFESS to having been somewhat surprised upon learning about another book on that doomed cowboy-on-cowboy love story, Brokeback Mountain. But as editor William R. Handley shows in this new anthology about Jack and Ennis’ tortured, unrealized, lifelong love affair, there is still more to be said about the movie that elicited such a wide range of responses, so many of them extreme and at odds with one another, since the movie’s 2005 release.

David Leavitt asks whether Brokeback can really be called a gay film at all. Daniel Mendelsohn makes the reasoned but adamant argument that one of Brokeback’s major achievements is that it is a gay love story—as opposed to a universal one, a line that many critics at the time used to disavow the potentially unappealing “gay movie” label. There follows a response to Mendelsohn’s screed by James Schamus, one of the film’s producers.

Fans of the movie will appreciate LA Times film critic Kenneth Turan’s succinct but severe admonishment of the Academy, making the charge that the reason Crash won the coveted Best Picture Oscar over Brokeback was simply because the issue of racism is a safer bet than that of homophobia. His final line is a brilliant sentence of condemnation: “Sunday night’s ceremony proved it is easier to congratulate yourself for a job well done in the past than actually do that job in the present.” Fans of Vito Russo’s Celluloid Closet (1981) will recognize Turan’s sentiment right away, as it echoes one of the final lines in Russo’s essential book: “Hollywood is yesterday, forever catching up tomorrow with what’s happening today.”

Russo’s potent arguments are addressed in separate essays by Chris Freeman and James Morrison, who point out that while the tragic ending of Brokeback appears to be out of step with Russo’s plea for happier lives for gays onscreen, the demands of the melodrama genre mean that a tragic ending is somewhat obligatory. Another standout piece is Judith Halberstam’s often hilarious critique of those who felt that Brokeback was radical because it dragged gay themes into the Western, a genre that has always been loaded with gay themes, motifs, and imagery, as Warhol made perfectly queer in his blatantly homoerotic 1968 film Lonesome Cowboys.

While the book does examine the machinations behind the scenes—notably the decision to film the movie in Alberta, Canada, often considered a bastion of homophobia—the role of the Hollywood star system goes strangely untouched. And in that lies one of the biggest contradictions that Brokeback illuminated. Despite Hollywood’s ongoing homophobia, many critics have noticed that playing a gay role will greatly enhance an actor’s chances at an Oscar nomination (and some snickered that Heath Ledger got bonus points for playing the bottom). But both actors went out of their way to confirm their off-screen heterosexuality, reconfirming that actors willing to play gay must be straight in real life in order to attain A-list status.

The fact that The Brokeback Book evoked so many questions about same-sex representations on-screen and their effects on viewers demonstrates the worth of this volume, whose essays offer considerable merits. The debates are clearly destined to continue for some time to come.

________________________________________________________

Matthew Hays teaches film studies at Concordia University in Montreal and is the author of The View From Here: Conversations with Gay and Lesbian Filmmakers .