GAY FAULKNER: Uncovering a Homosexual

GAY FAULKNER: Uncovering a Homosexual

Presence in Yoknapatawpha and Beyond

by Phillip Gordon

Univ. of Mississippi. 279 pages, $25.

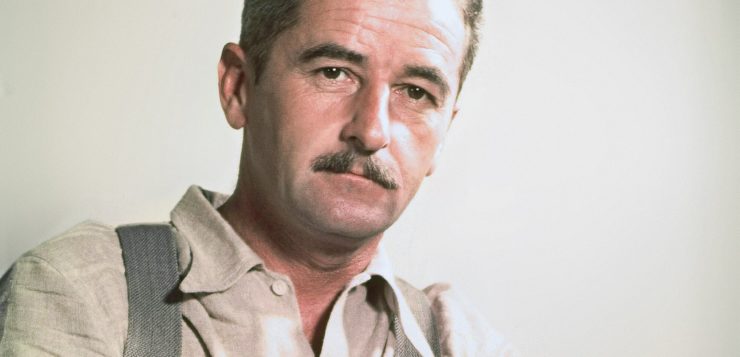

WHEN I SAW the title of this Faulkner study, researched and written by a professor of English and gay studies at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, my first reaction was a “What?” of disbelief. I’ve read most of Faulkner’s novels and many of his short stories and the gay hypothesis never occurred to me. Faulkner struck me as the epitome of the straight, married, traditional Southern author, living his life far from the up-to-date delights of the metropolis.

But it appears that I didn’t read closely enough; nor had I happened on earlier studies of the author’s work that gently open the topic of queerness. Young Faulkner’s self-presentation was affected enough to be called “quair” by the more conventional residents in Oxford, Mississippi, writing decadent poetry and adding dandyish touches to his outfits. Professor Gordon doesn’t claim unequivocally that Faulkner ever engaged in same-sex acts. He only allows for the possibility that it might have happened with a pretty undergraduate at Ole Miss named Ben Wasson. Their friendship began in 1910 and continued throughout Faulkner’s life, taking on a business aspect when Wasson worked as the author’s literary agent for several years. It seems that during the early phase of their friendship, they spent long evenings together at a friend’s house during his absence, the two listening to music and discussing the arts.

Circumstantial evidence in support of Gordon’s argument can be found, too, in the aspiring young author’s military record and his aggrandized presentation of it. He spent about six months in training in the RCAF but never crossed over to the European theater. On his discharge, he bought an officer’s uniform he wasn’t entitled to wear, wore it on the streets of Oxford, and affected a limp presented as being the result of a combat injury. If you like, this bit of cosplaying can be understood as one element in an overall pattern of dissembling. And what else could LGBT people do but dissemble in the period before uncloseted lives were accepted? It was necessary for survival, and we see that Faulkner had notable acting skills.

I might as well, in support of the gay surmise, make a couple of extra observations about Faulkner that Gordon doesn’t mention. When Faulkner read Moby-Dick, he described it as “one of the best novels ever written,” and in later interviews cited it as a major influence. Is that because he had special insight into the queer friendship between Ishmael and Queequeg? One more thing: for a year or two in his early phase, Faulkner served as a scoutmaster, a role that doesn’t quite fit his pose as dandified bohemian poet—unless it does.

Professor Gordon fills out his biographical forensics with a close critical inspection of Faulkner’s work, focusing on early stories like “Moonlight” and “Divorce in Naples,” where same-sex orientation and activity are strongly implied. But he finds gay themes even in the novels of maturity. For example, he notes that Darl Bundren in As I Lay Dying is described several times as “queer,” just at the moment in social history when the word had acquired a homosexual connotation. The same hypothesis is applied to Homer Barron (“barren”?) in the novella A Rose for Emily, and the case made is certainly credible. Gordon trains a queer eye on many Faulkner works with solid results.

The presumably straight author understood better than most men in this category that gay people exist as a regular part of society, and therefore merit fictional treatment. Was that knowledge the result of chance friendships made early in life, or should we conclude that Faulkner was in fact a closeted gay man who never—or perhaps only once or twice—acted on his desires? This book doesn’t say. What it does say is that we may trace Faulkner’s scheme of creating a mini-universe in his fictional Yoknapatawpha County (a setting where the closeted gay character V.K. Ratliff lives and moves) back to its origins in the writings of the closeted gay English author Walter Pater. Gordon sums up his assertion this way: “Thus, in the twilight of The Mansion at the end of Faulkner’s brilliant career, as Ratliff leads Gavin Stevens to find Mink Snopes, we can recognize that this cosmos of Faulkner’s own is a gay cosmos and the heart of Yoknapatawpha is a gay voice still talking beyond the end of the world and into ours.” This grand statement (or overstatement) will be useful at the very least in stimulating critical debate, and I look forward to hearing responses to it, hoping, too, that they will be temperate and respectful.

We might use Gordon’s study as an occasion to reflect on those individuals who experience same-sex desires without ever acting on them. In Existentialist philosophy, “Existence precedes essence,” which means you are what you do—that identity arises from deeds rather than mentality. If Faulkner never had sex with another male, was he gay? In contemporary Roman Catholic teaching, you are allowed to have queer thoughts so long as you never put them into action—a teaching that must have been greeted with sighs of relief by thousands of closeted priests, just as it struck terror into the hearts of those who had put their thoughts into action with minors. My conviction is that feeling and thought define who we are as much as action. If someone remains celibate for an entire life and yet experiences same-sex desire, then that person ought to be classed under the LGBT umbrella. Which is why gay oldsters, who have (so to speak) passed the age of consent, still do qualify as gay because of their thoughts and feelings. If we accept this broader definition of LGBT identity, then the case is strong that Faulkner fits into it under the “B” heading. Just possibly he and Ben Wasson got to first base a few times at least. But there is little chance now that this possibility can ever be confirmed, any more than that it can be disproved.

Alfred Corn is the author of eleven books of poems, two novels, and three collections of essays. His new version of Rilke’sDuino Elegies will be published by Norton in 2021.