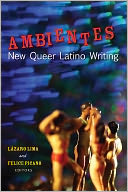

Ambientes: New Queer Latino Writing

Ambientes: New Queer Latino Writing

Edited by Lázaro Lima and Felice Picano

University of Wisconsin Press. 206 pages, $22.95

THE WRITERS in this new anthology of short stories are doubly disenfranchised: first, by the dominant national discourse, which continues to use racial and ethnic categories when defining what it means to be an American; and second, by a tacit understanding within the Latino community that heterosexual relations are better than homosexual ones. In this vein, the seventeen stories included here challenge these obstacles by celebrating a group of voices that joyously affirm, “We’re here, we’re Latino and queer, get used to it!”

The name of the volume, Ambientes: New Queer Latino Writing, attests to the importance of language for queer Latino writers as it annuls linguistic hierarchies through its Spanish title and English subtitle.

Linguistic subversion is accompanied by a systematic questioning of other social categories, notably those associated with male and female roles. Indeed, many of the characters represented in the stories cross over the gender divide. The narrator of Arturo Arias’ “Pandora’s Box,” for example, is transformed magically into a woman: “The first thing I did, once in the privacy of my home, was take my clothes off frantically and explore my body. I felt like a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, breathing way too fast for my own good, afraid of the nothingness between my legs.” Although Arias treats the subject matter within a comic register, the challenge to established roles subtends the narrative. Other characters emphasize marginality and danger: the narcotraficantes or drug-dealers in Myriam Gurba’s “Malverde”; the bandit drag queens in Charles Rice-González’ “Puti and the Gay Bandits of Hunts Points”; Pesticida’s obsession with the Tex-Mex singing star Selena in Ramón García’s “Imitation of Selena.”

Given the position of queer Latinos in today’s political landscape, it should come as no surprise that many stories are tinged with violence. “Kimberle,” the opening story by acclaimed author Achy Obejas, describes the unfolding relationship between two women, the narrator and the title character, in an Indiana town besieged by a serial killer’s annual ritual murder. Obeja’s writing deploys beautiful alliterations and images (“Her words slid one into the other, like buttery babies bumping, accumulating at the mouth of a slide in the playground”) all the while depicting a dysfunctional relationship and paying homage to literary works found in the narrator’s personal library, which includes Richard Wright’s Native Son, Sapphire’s American Dreams, and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. Other stories enact a more subtle—yet perhaps more insidious—violence, such as Rigoberto González’s “Haunting José,” in which the ghosts of his family become an allegory for the exiled condition of those rejected by society.

The anthology presents a wide array of stories from men and women, from gays and lesbians, from established writers and promising young ones. Furthermore, the collection brings together different national backgrounds and the stories are set all over the U.S.—from New Orleans to St. Paul, from Indiana to California. It should be noted that the editors have made available an ancillary website (myambientes.com) where readers can learn more about the authors and editors. A pedagogical framework will also be added for teachers and activists who want to incorporate the anthology into their courses. Through education, the stories collected here will reach a broader audience thereby enlarging the traditional canon to include a more realistic and just choice of texts representing our national literary scene. Indeed, in his preface, Felice Picano recounts an anecdote about Latino students coming to him after a reading; the students approached him to express their enthusiasm about having an openly out Latino gay writer as a role model. Though of Italian descent, Picano admits that he is Latino “in a way.”

Ambientes is a timely contribution at this point in history during which demographic shifts are literally changing the face of America. The stories in Ambientes provide a significant model for GLBT Latinos in the U.S., giving them the tools to find their own voice by uncovering a community that has long been neglected and silenced. By raising nuestras voces and joining national dialogues, we participate in what José Muñoz calls (in the introduction) “a utopian future of democratic possibilities” and work towards a horizon of recognition and liberation.

________________________________________________________

Eduardo Febles is an assistant professor in the Modern Languages Department of Simmons College.